Gratitude

How to Navigate the Perils of Creative Success

A case for magic, fairies, and gratitude

Posted August 12, 2015

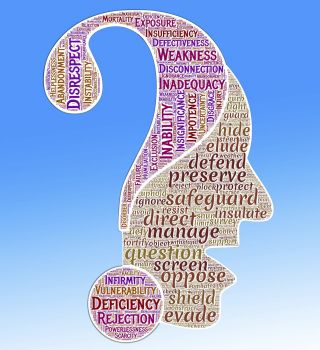

From the outside, success seems to be an enviable state of affairs, even a balm for the insecurities that so many of us feel. But for some people, especially for creative types, there are perils that come with success. It is crucial to pay attention to these perils because they are linked to some very painful experiences such as paralyzing creative blocks, performance anxiety, procrastination, depression, relationship troubles, substance abuse, health problems, and even early death.

Highly creative people tend to be highly sensitive people. Plagued by perfectionism and self-doubt, they often struggle to do the work required of success, even though they clearly have the talent for it. We all probably know a talented someone whose progress was thwarted by the debilitating worry that their work wouldn’t be good enough. The underlying belief may go something like this: if it’s not perfect, it’s no good. And then the deeper belief: if it’s not perfect, I’m no good.

After having some success, the inner dynamic lives on but takes a different shape. The successful person may worry that the success he or she has achieved will be taken away. After all, success isn’t static; one doesn’t arrive at success once and for all. You have to keep it going. The debilitating anxiety of this state of mind is linked to an underlying belief that goes something like this: if I can’t do it again, it means that it was a fluke. And then the deeper belief: if I can’t do it again, it means that I am a fraud and was never any good in the first place.

In my experience as a sensitive, creative person and listening to sensitive, creative people, it seems that such personality types have a disproportionate sense of responsibility—they are quick to take the blame for failure and crave the admiration that comes with the success. This is a perilous place because one’s good sense about oneself then depends on the success. It’s too much pressure, especially for the creative process which requires so much vulnerability, risk taking, and courage.

There are two ideas from psychoanalysis that may help us move forward in better navigating these perils. The first is the idea of separateness, which involves the capacity to not take things so personally. Easier said than done, I know! But it is so helpful to be able to step back from one’s work—even from one’s relationships, audience, and critics—and to claim some separateness from it. In other words, you are not your work, I am not my blog. We are connected to them, yes, but that is different than being them. To my mind, the capacity to be separate is the Holy Grail of mental health.

The second idea that may be useful in navigating the perils of success is to understand the pressures of omnipotence. While at one level, perfectionism is driven by anxiety rooted in low self-confidence and esteem, in another sense it is rooted in an inflated sense of personal power and self-importance. Omnipotence fuels the belief that I am the center of the universe and that everything depends on me. It fails to recognize that there are other people and other forces at play in our lives. The appealing upside is that, in this state of mind, when we succeed, we deserve all the credit. The miserable downside is that when we fail, we then deserve all the blame.

Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the freakishly successful memoir, Eat Pray Love, explores these dynamics in her 2009 Ted Talk, Your Elusive Creative Genius. With her new podcast, Magic Lessons, and her forthcoming book, Big Magic, Liz is on a mission to help creative people live longer, more stable lives of ongoing creativity by helping them find some separateness from their work and lifting the burden of omnipotence.

In her TED Talk, Liz pitches a radical idea as an antidote to the perils of creative genius. She makes the case for bringing back our belief in fairies. She tells of a time in our collective history when creative people were not so burdened by the pressure of success because they did not believe that they had earned the success alone. There was a cultural understanding that great genius came from the other side, the work of another genius in the form of fairies or the gods. The artist was seen as a conduit, a vessel. It meant that neither success nor failure belonged to the artist him or herself alone. The burden of both success and failure was shared.

It might surprise you that a psychoanalyst would be inclined to think of such an idea as helpful but, in fact, I do. I think that there is something liberating about the idea that our work is not entirely our own. After all, as a psychoanalyst, I believe in the mysterious unconscious with its myriad figures and phantasies that influence us profoundly. Then, there is Carl Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious with the awareness that we are impacted by all that has come before, that we are connected to the universe in real, transcendent ways. In his later writings, psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion tried to convey this sense of the numinous in his idea of “O”—an ineffable presence within and beyond, the source of truth and life.

There is another, perhaps less mystical, psychoanalytic perspective that may help us here as well. Psychoanalyst Melanie Klein developed her model of mental health and well-being around the idea of gratitude. She believed that a satisfying, full life is rooted in the capacity to view one's life fundamentally as a gift. She suggested that gratitude can help liberate us from the chains of omnipotence because we give credit where credit is due: to our parents and their parents and their parents before them—parents both literal and figurative. In so doing, we recognize that others share both our success and our failure. Such perspective has a way of turning down the pressure.

If we can slowly shift our mindset from seeking success in order to prove our worth to seeking to use the gifts we have been given, we have more reliable protection from the perils of success. Gratitude brings awareness of the other, which helps us to be separate. Gratitude puts us in a position of helpful dependency and humility, which are antidotes to omnipotence. It opens up the possibility that we might be able to better enjoy and use the gifts we have been given.

Copyright 2015 Jennifer Kunst, PhD

Like it! Share it!

Follow me on Twitter @CouchWisdom

To learn more about these useful ideas, check out my book, Wisdom from the Couch: Knowing and Growing Yourself from the Inside Out and my website, www.drjenniferkunst.com