Cognition

9 Ways to Make Yourself Smarter

Better thinking, with or without technology.

Posted November 24, 2013 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Knowing when to shift between public and private thinking is a crucial new skill known as cognitive diversity.

- A huge amount of valuable thinking happens when people work in groups rather than alone.

- Automating a task too early with machines can take away an individual's opportunity to deeply learn it.

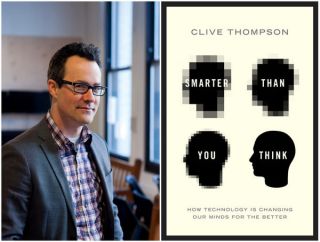

I recently spoke with the technology journalist Clive Thompson, author of Smarter Than You Think. I came away with nine lessons on how we can improve our thinking and become smarter—with and without technology:

1. Spend Significant Chunks of Time Offline

“I think it’s good to spend significant chunks of time offline. For example, I don’t check my email on weekends. This means I’m usually off social media. I’ll text a bunch because that’s social for me and how I organize social behavior. But I tend to get more reading done and my brain gets pulled in a cooler direction. And a lot of people tell me they can’t do that because their boss demands they check their email on the weekend. And this shows that a lot of the problems of distraction we have are not really latent in the technologies themselves, they’re latent in the power relations that emerge from those technologies.

"White collar workers probably need to have a solidarity movement that equals that because their labor is now constantly squeezed by employers who have the ability to reach them 24/7. The smart employers recognize that it’s actually bad for the caliber of their employees' thought to be constantly pecked at like ducks all week long. And I think Volkswagen and a few other firms have instituted this policy of turning their Blackberry servers off after a certain hour at night and on the weekends, so there’s no email coming into their employees … This is what the unions have been espousing for a hundred years. The weekend works. It’s a civic and social good, and for an employer, it should be a corporate good too. Let people disconnect from your corporate demands.”

2. Engage in Cognitive Diversity: Do Something Mentally Different

“One of the things I talk about in my book is the need for what I playfully call cognitive diversity. If you buy the idea that the way we communicate and write, express, and form our ideas online is qualitatively different from the ways we do it offline, and that those are productively or usefully different from traditional less social thinking offline, then it’s still incredibly useful to read for eight hours, go for a long walk, or just argue about something drunkenly at a bar with a friend. These things are sufficiently different from the ways we conduct ourselves online, and drag your mind in usefully different modes of thought.

"The same is true of just doing something different with your body. The reason why we get ideas in the shower is because we’re not working and our bodies are doing something totally different; it’s a new stimulus environment, and the stuff we’ve been ruminating on just assembles itself in a completely different way in our subconscious. So, if you’re a person who works with words all day long like I do, it’s really good to do something completely nonverbal in your spare time. I’m an instrumentalist, so I’ll play guitar for half an hour at the end of the day, and it’s a fabulous way to put my brain in a totally different embodied state. I often come away from it having solved some sort of problem … And it is very emotionally valuable as well, which exercises whole other parts of my personality. Everyone’s got something like that. Some people like to cook; they’ll spend eight hours on Sunday doing a fantastic Indian food dish, running, playing team sports. These are all things that are connected to the quality of our overall lives and thinking. Knowing when to shift between public and private thinking—when to blast an idea online, when to let it slow bake—is a crucial new skill: cognitive diversity.”

3. Don’t Isolate Yourself: Learn Social Thinking

“Our intelligence has never been entirely just in our heads. A huge amount of our thinking is what the philosopher Andy Clark would call taking place in the extended mind, which is to say, using all sorts of resources outside of us to help scaffold our thinking in new directions and capabilities that are impossible with the mind alone. That ranges from something as simple as being able to write something down so you no longer have to hold it in your head for the short or for the long term. A huge amount of human cognition has relied on resources outsides of our heads in the same way that the basics of our memory relied very heavily on social dynamics, social remembering, or what psychologists call transactive memory.

"When groups of people hang out they are very good at retaining meaning, but we’ve relied on other people as sort of these cognitive amplifiers. So you could ask the question, are we dumber if we’re not around other people? Are we smarter if we’re near them? I think the answer is yes, we are smarter when we are around other people, we are smarter when we are around all sorts of external scaffolds for our thinking, and that’s an essential definition of being human.

"One of the things my book tries to do is a huge amount of what we typically think of as intellectual work, which has always been very social and transactional with other people. We too frequently define intelligence and thinking as sitting and peering at a book alone for 10 hours or 10 years. And while that’s an undoubtedly powerful mode of thought, in the real world, a huge amount of thinking happens when we’re arguing, bickering, and relying on each other and working in groups. One of the reasons this has been denigrated is because socializing has been read as feminine—social skills and emotional intelligence. And you see this right now. All the sort of big thinkers out there complaining that social media is trivial and stupid are these middle-aged male novelists, right? Jonathan Franzen, for example. They say that unless you are isolated, and remain isolated, somehow your thinking is contaminated and shallow and trivial.”

4. Find Your Passion: It Drives Memory and Creativity

“Passion is what drives memory. We can now account for a more diverse array of information, and we can now have far more serendipitous encounters with knowledge and other people, so you probably get a net increase in creativity. But it is also true that if you want to have powerful creative leaps in the sense of going on a long walk and suddenly being hit by a bolt out of the blue, you have to deeply internalize knowledge. It is incumbent upon the person who wants to be creative to really wrestle with the material they are thinking about. So you have to have those disconnected moments where you can think without being distracted. You also need to do more idea generation, such as writing. This is enormously powerful for encoding in our heads what we’re thinking about.

"The distraction stuff has made things harder, but the generation stuff has gotten easier. Even arguing about things through email is a powerful way to get things to sink into your head. If we stopped lingering over the stuff that we cared about, you could argue that we are losing some creativity. In practice, I think when people are obsessed with something they do linger over it. So really what you have is a cultural problem. I would like people to be obsessed with space exploration more, with politics more, which is the age-old question of 'How do we get people passionate about the things that are the big things?' That’s what you and I are trying to do. We’re constantly trying to seduce people into thinking about science by posing it in a really delightful way. You attract more flies with honey.”

5. Don’t Just Follow “Thought Leaders” or the Elite

“I think what’s happening now with the internet is that the cultural elites—and I would probably include myself in that category because I’m a New York writer—are startled to discover just how diverse human interest and human passions really are. Because when you live in one of these cities on a coast, you think, 'Wow, everyone is really unified around X, Y, or Z because we’re writing about it.' But then you discover, no, no, no, people don’t care about that at all!

"For example, book scanning enables us to see what books people are actually reading. The New York Times doesn’t put together its bestseller list based on what books are actually selling; they put it together based on a handful of carefully picked bookstores in elite markets because that’s who they care about—thought leaders, to use one of the most obnoxious phrases coined in the last 10 years. Thought leaders.

"It turns out the country buys a gazillion Christian books and a lot of self-help, right? So as soon as we got information about what the average person was really doing, it didn’t in any way cohere with what the people—who thought they had a hold on canon—thought everyone should be talking about. And the internet has a little bit of that effect. Because it makes conversation visible it startles us with the diversity of what people actually care about.

"One of the things I think is really unsettling about the internet and the way it has transformed society is how little people actually care about the things we thought they should care about. This is always what freaks out cultural elites. They thought everyone cares about the same five books they read. But online everyone’s talking about Twilight, their fantasy sports league, Pokemon, their Tea Party meeting, gardening, and knitting. And the elites are like, 'Oh my God, why is everyone so dumb?' And by dumb, they mean, 'Why isn’t everyone reading the same five books I'm reading?' ”

6. Know When (and When Not) to Rely on “Outsourced Intelligence”

“If you automate skills that shouldn’t be automated, you degrade the quality of your performance and thought. We have Google self-driving cars coming along. On the one hand, this is great because humans are dreadful drivers. We should not be driving. We have terribly wandering minds and are too easily distracted. We are overly confident in our abilities and have a dreadful sensual appreciation for the kinetic power of a two-ton object moving at sixty miles an hour. I would way rather have a robot controlling the car. The danger of this comes when you have to suddenly hand the control back to a human.

"I’m in the car and sleeping, playing a video game, not paying attention, or reading a newspaper, and suddenly my self-driving car says, 'Oh my God, something is happening that I can’t handle. Here, Clive, you drive.' And maybe I haven’t actually driven the car for two years now. So I’m probably going to be a disastrously bad driver. When you hand something off to a machine or an algorithm, you can lose the habit of doing that task. This is a really interesting problem and I don’t know how they’re going to get around that with self-driving cars. The statistical answer is if I am handed back the car, I likely will crash it. But the overall damage rate of handing off control of cars to robots will still be so much lower that it’s worth it.

"So how does this analogize to cognitive tasks that aren’t so life and death? One example is with calculators and learning math. The evidence seems to show that if you give a kid a calculator too early in their learning, they won’t learn it quite as well because they don’t get the chance to really wrestle with those procedures. It’s even bad to routinize or hand over to an algorithm the act of addition with carrying. Studies show this prevents the kid from thinking about what the numbers mean. I see this in my kids. Teachers present the algorithm but they also teach different ways to think about the numbers. Once you’ve grasped these basic math concepts, using a calculator is fine and this actually improves our ability to learn math, discover more playful combinations of numbers, and ratchet ourselves ahead.”

7. Play Video Games, the Gateway Drug to New Learning

“I became aware early on, that as Dave Weinberg says, 'everything is miscellaneous.' Whatever it is you care about, there are more people that don’t care about it than do. Your passions are someone else’s miscellaneous stuff. So playing video games is useful in learning cultural humbleness. The second thing is that video games got me interested in computers. They were a gateway drug to thinking about the role of computation in people’s lives. They got me interested in programming, which gave me a glimpse into the superstructure of software. And they’ve given me an enormous amount of existential joy, which doesn’t get talked much about. Since video games have been under assault for so long as a waste of time, people have trouble expressing what it is they find joyful about these games. And there have finally been a bunch of intellectuals who have begun to grapple about what’s good about games—not about what they teach you or if they improve your hand-eye coordination or working memory—they are asking as a philosophical enterprise what are they good for? Why do we love them?

"Regarding gaming and problem solving, I think games are a fantastic opportunity for illustrating a couple of things that educators often complain they have trouble getting kids to understand. One of them is the scientific method. We talk about how if you’re confronted with a problem where you must generate a hypothesis, then you must do an experiment to figure out whether your hypothesis matches reality. Collect your data, refine your hypothesis, and do it over and over and over again. But it’s hard to get kids to really understand this because we give them mock experiments to run where the results are already known. We never give them a really invisible problem and ask them to make the rule set visible. We never tell them you need to figure out whether the Higgs-boson exists. They don’t have the tools to do that. We’re bad about giving them problems with invisible rules that they are excited about uncovering. And until we do that, they’ll never really understand what is powerful about the scientific method.”

8. Be Willing to Adapt Your Thinking Strategies

“I’m pretty optimistic about the adaptability of our thinking strategies. For example, I am a big marginalia taker in books. It’s how I make sense of a book. And you could say there’s a wonderful kinetic feeling to that and I write more slowly than I type, so am I encoding that knowledge in a better way?

"You can do these swoopy little cool connections where this part is connected to that part. And there’s this spatial memory about where it is in the pages, and that’s lost when you work digitally, right? But on the other hand, when I take notes on my Kindle, I can move a little more quickly when I’m typing so I put in a longer and more thoughtful idea. Sometimes I’ll even write two paragraphs, which you can’t do in the margins of a book. And, more importantly, you can re-encounter those notes by putting them into a database, so when I search for them I can find notes that I had forgotten I had taken from a book three years ago.

"Recently I’ve been tweeting couplets from Alexander Pope’s essay on man because he’s one of my favorite poets—from the 18th century, he’s my overall favorite poet—and I read it on the Kindle. I kept on highlighting these wonderful couplets. And so I called up the notes and I’ve been tweeting these couplets. And there’s no way in hell I would do this with my paper book. I would literally forget it was there. I do 50 percent of my notation on paper and 50 percent on Kindle and I don’t feel there is a big difference in the quality of my thinking, only that it’s easier to encounter what I wrote in the digital format. And that re-encountering is so explosive in value.”

9. Use Technologies to Amplify Your Intelligence

“I absolutely think that writing concisely and pithily is a more recognized value now than it has been for some time. We have some tools now that encourage pithiness, for example, Twitter. People mock Twitter: 'What can you really say in 140 characters?' But I think what we’ve discovered is that people can say delightful things. It forces them to boil down what they want to say; it forces them to be incredibly witty. As Shakespeare wrote, 'Brevity is the soul of wit.' An aphorism itself that would fit perfectly into a tweet with room left over.”

© 2013 by Jonathan Wai

LinkedIn Image Credit: Jacob Lund/Shutterstock