Depression

Why Create Minor Characters in a Novel, Story or Essay?

What is the role of a minor character?

Posted March 30, 2015

Russian stories are often filled with a vast number of minor characters whose names we may find difficult to pronounce or remember. So why does Turgenev, for example, in a short story like Mumu (1854) give us not only his main character, Gerasim, the wonderful deaf and dumb serf, but the woman he belongs to, as well as a tailor, Kapiton Klimov who is a sad drunkard but who regards himself as unappreciated, driven to drink by his sadness? There is also the head steward, Gavrila who is precisely described with his yellow eyes and nose like a duck’s beak.

The plot thickens when the lady of the house decides to marry the tailor, Klimov off in the hope of redeeming him and making him steadier which of course brings in the love interest in the story, who is Tatiana, the young laundress who is also beloved by Gerasim who is so immensely strong and tall.

Of course, all these characters are useful for the triangular plot, but also to convey a sense of Russian life in all its diversity at that time. We have the different classes represented: the serf owner, the drunken tailor, who is also an educated man who considers himself hardly done by; there is the pretty young laundress and ultimately the moving portrait of the hero, Gerasim, who though a serf attempts to assert his independence in the only way possible, in an act of desperation.

But perhaps the most important minor character who is brought in half way through the story is Mumu the beloved little dog who evokes all our sympathy for Gerasim who is obliged to drown him.

If we turn to Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” there are a plethora of minor characters who serve in various functions and I can only mention of few here: Razumkhin, the hero, Raskolinokov’s great friend, seems juxtaposed as a foil to Raskolinikov, in his complete goodness, his dependability, and his physical strength ( like Gerasim he can fell someone with one blow.) Whenever he comes on the scene we breathe a sort of sigh of relief. After Raskolinkov’s extreme turmoil and despair, he seems calm, reassuring, and “normal.” He provides us with a haven of stability in the rough sea of the murderer, Raskolinkov’s troubled mind.

There is Nastasia, the maid, who also provides some comic relief and kindness and anchors us firmly in the real with her laugh and her ability to appear at all hours, it seems, with cabbage soup and tea.

There are the policemen who are juxtaposed to one another, Ilia Petrovich, who is the assistant superintendant who is so irascible with his reddish moustache and Nikodim Fromich who is the superintendant and much calmer and more savvy.

There is the German woman who appears in the police office, a smartly dressed lady who contrasts with Raskolnikov’s wretched attire and again produces some sort of comic effect, in her attempts to be seductive with the terrible police officer who vents his venom on her. “Mine is an honorable house Mr. Captain and honorable behavior Mr. Captain,” she stammers and stutters telling her story in Russian with a sprinkling of German.

All these characters serve several purposes. They further the plot: the two police speak of the murder that has been committed and cause Raskolinikov to faint thus endangering himself; they give us a realistic portrayal of the divisions and inequalities of the society in that time and place, and they are able to echo off the main character to reflect and contrast, thus deepening our appreciation of the hero himself.

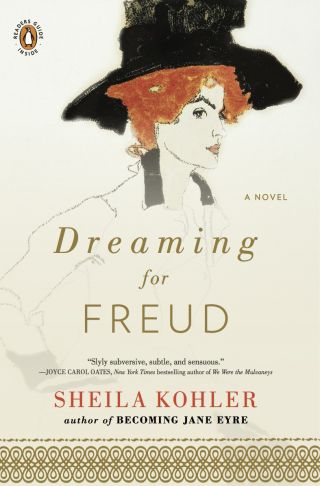

Sheila Kohler is the author of many books including "Becoming Jane Eyre" and the recent "Dreaming for Freud" http://Amazon.com Dreaming for Freud.

Becoming Jane Eyre: A Novel (Penguin Original) (link is external)by Sheila Kohler Penguin Books click here(link is external)

Dreaming for Freud: A Novel (link is external)by Sheila Kohler Penguin Bookshttp://Penguinbooks click here