Autism

Using Structure To Help Autistic Kids Build Flexibility

A tool to develop flexibility.

Posted March 31, 2014

A few weeks ago, during a weekly Twitter chat that I host about autism, a mother of an adult on the spectrum mentioned how, when her daughter was a child, structure had been crucial in helping her to learn flexibility. It sounds like an oxymoron, but I found it to be absolutely true in my life as well. When I look back my early childhood years and try to figure out the things that worked best for me, structure is a repeated motif. In fact, I think it was one of the most important aspects of my growing up years — and it helped me in many ways.

It’s nothing new to say that autism and anxiety often go together, it’s been stated that up to 84%of people on the spectrum are affected by it. One major driver of anxiety can be not knowing what to expect from a situation. As an adult I experience this fairly regularly in social situations which are less than predictable. A large amount of my cognitive resources are spent in any given day on imagining the various ways different situations could play out, and imagining the best way to react. It’s something the neurotypical members of my family have never really understood that well. To them it just looks like worrying and rumination, but for me it’s a critical survival skill.

Having these “imaginary rehearsals” give me a sense of what is coming, and minimizes the chances that I may choke when the situation actually arrives. Without them, I may freeze or lose speech, or blurt out something embarrassing or inappropriate. It feels like what happens when you attempt to interact with a computer that has no operating system, or when it is given a command that software does not know how to handle. These types of rehearsals can only happen if you have a sense of what’s going to happen next. Without that knowledge, the anxiety can become overwhelming to the point of panic, especially for someone who has a traumatic list of memories of that happened due to lack of preparation.

I’ve written before of the program that my parents sent me to from kindergarten to third grade. It’s something I’ve always struggled to explain to people who weren’t there, but one of the things that sticks out the most about it was how integral structure was to their approach. When I’d try to explain it to my peers, after having left it, my peers would often make negative comments. “That sounds awful,” they’d say, leaving me stymied. But the fact of the matter is I can’t remember a single child who was there that shared the same opinion. I had to conclude that I must somehow lacked the proper capabilities to capture the spirit of the environment.

What my peers were reacting to in my explanation was exactly what made it a comfortable environment for me and many others—structure. Rules. Consequences. Predictability. In the end, what child will actually admit to liking rules? But for me, having rules explicitly communicated along with their consequences made the world a lot less frightening. If you’re not the type of person that can pick up on social rules by osmosis, then the world begins to feel like a torture chamber of random punishments.

How fair is it to punish a child for violating a rule they didn’t know existed? Yet, it happened to me all the time, until I came to a place where they didn’t assume that I would “just pick it up,” and made a point of making sure that I knew and understood. I didn’t appear to be the only each child that blossomed under this. Today, I’m not surprised to read in parenting advice columns and books that rules and structure are important. I saw it firsthand.

Likewise many of the rules that were enforced were rules that helped us to learn valuable lessons. For example, one of the bedrock rules every kid knew was that homework came first. When we arrived back at the proprietors’ house after being picked up from school, we knew we would be asked if we had homework. If we did, we knew that there was no other option but to join other kids in the kitchen to sit and work on it. The founder of the program was a former teacher, and just like she would have in a classroom, she kept a grade book in which she made notes. She would work with each child one-on-one when they needed help, and would stay with us as long as necessary. Any child who was caught lying about having homework so that they could go play first would face consequences. We were expected to be responsible and disciplined in an age-appropriate way, and it taught me lessons that still serve me well to this day.

When the participant in my chat talked about structure as a driver for flexibility, I reacted with excitement. This was something I'd found crucial as well. For example, at the program I went to they had rules about what we could eat in our lunches. Given the number of children they had at their home at any one time, they did not have the resources or equipment to cook lunches themselves, so we had to bring bag lunches. They were believers in the value of nutrition for children, so they made rules about the makeup of lunches to help drive kids to eat a variety of foods, that were on the healthier side.

This, I believe, help me a great deal to expand my diet. In fact, in retrospect, I often find it ingenious in they way it fit so well with my particular cognitive profile. As is not uncommon among autistic kids, I was not fond of change, although I’d had to deal with my share of it. But the way they chose to structure their rules helped to make change less scary. In the case of lunches, the rules were fairly simple — lunches must consist of a vegetable, a fruit, a sandwich or protein-based food, and juice. None of the foods could contain sugar. So, how did rules make change less scary?

When I think of that, I think of an example that Temple Grandin gave it her TED talk, “The World Need All Kinds of Minds.” In it, she gives the example of a horse who is afraid of riders wearing a black cowboy hats, but riders wearing white cowboy hats were perfectly fine (see 9:48 in the video). She explains that this is a side effect of being a visual thinker. That small changes to what one sees in a picture are experienced as an entirely new picture. Being a visual thinker myself, this makes sense to me. It sheds some light onto why changing a meal was stressful for me. If I was asked to incorporate something new or switch out some component of my meal, I experienced this as a complete change of the meal. A new picture.

This is where the “modularization” of lunches served to help me build flexibility. By breaking the concept of “lunch” into discrete sub-concepts, it broke the “picture” of lunch into separate pictures that could be combined and separated at will. This made it easier to see the scope of change being asked for. If I was asked to try a new type of fruit, I could still see that my choice of vegetable, sandwich, and juice were the same. So, my parents worked with that. I may have eaten peanut butter sandwiches almost every day for four years, but I gradually developed a taste for a variety of vegetables, fruits, and juices.

Picture via Tesla Aldrich: https://www.flickr.com/photos/12579989@N00/

My father used to take me to a large farmers market out in one of the more agricultural areas further from the city, where we would look at all the different types of fruits and vegetables available. I liked it especially because I could see the animals, and enjoy a quieter more peaceful environment. In this calm state, I came to really enjoy the smells as we wandered through the large tents where row after row of different colors of apples or oranges stretched seemingly endlessly. I was drawn to the colors, and sometimes the sounds. Eventually, kumquats became one of my favorite fruits. I was drawn to it, not due to the shape or taste, but because I loved the name. I thought it “stimworthy.” It was fun to say, and fun to hear — and that affinity led to me like eating them.

This same type of structure was used throughout my time in this program, in various forms. Our days were always structured, whether they were schooldays or not. In the summer, every day of the week had a different activity theme. We had a bike day, a hike day, a beach day, and a trip day, always on the same days of the week. We always knew what type of activity we would do on a Monday or a Tuesday, but details of that activity would be different each week. One week we’d ride bikes to one local landmark, another week we’d ride to a different one.

It was the same, consistent, yet not. There was always familiarity along with the variation. Every bike day, we knew we’d get a rare sugary treat, yogurt push ups. Every beach day, we’d know we would cook hot dogs for lunch. Trip days stretched me the most. A trip day could mean very different things. It could mean visiting a museum, or it could mean visiting an amusement park. But, the schedule was always posted weeks ahead of time, so I had ample time to prepare myself.

On school days, we would use a structured technique to choose what group activities we wanted to do after everyone finished their homework. We would be called together into a circle, in which the adults would lead the conversation. They would ask for ideas of what we wanted to do. It was known that our options were limited by the amount of adults available to supervise. Every group playing always had an adult supervisor embedded in the play to structure it and ensure nothing went awry.

The children would indicate their interests in the different activities, and we’d choose the few most popular. If any tied in popularity, the adults would act as tie breakers, as they would also if any particular activity group had to be pared down to avoid overloading a particular adult. This method allowed us to make our wants known, and give us a certain level of control, while still maintaining structure and adult control. We also knew, that if it turned out that the activities we suggested did not turn out to be the ones chosen, we knew that we had to learn to go along.

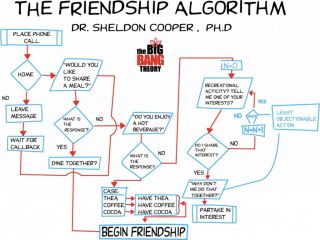

This taught me a valuable lessons about flexibility in social situations. One that was demonstrated in an episode (The Friendship Algorithm) of The Big Bang Theory. Sometimes friendship and being with others requires choosing the “least objectionable activity.”

And, sometimes, you learn to like it.

For updates you can follow me on Facebook or Twitter. Feedback? E-mail me.

My book, Living Independently on the Autism Spectrum, is currently available at most major retailers, including Books-A-Million, Chapters/Indigo (Canada), Barnes and Noble, and Amazon.

To read what others have to say about the book, visit my web site: www.lynnesoraya.com.