Psychology

Toward a Psychology of Wonder

Personal Perspective: Why my family has adopted "Wonder" as our central motto.

Posted July 5, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

I sat down with my family a couple of months ago and finally did one of those “family purpose statements” I’ve heard about in which each family member comes up with individual values and then you all see if you can merge them into something succinct. One word my 32-year-old daughter, Maia, had on her list captivated us all: Wonder.

It's such a great word, don’t you think? Maia led us into some of its meanings: Awe, inquiry, curiosity, questioning things, wandering, joy.

We adopted wonder as our central motto. It doesn’t hurt that it conjures a 1970s Lynda Carter vibe. I always did dream of flying a glass plane.

It feels good to be a wonder family. We don’t need to get too comfortable. We like having something new to wonder at. And we like that book by Langston Hughes: I Wonder as I Wander.

He writes, “If you want to see the world, or eat steaks in fine restaurants with white tablecloths, write honest books, or get in to see your sweetheart, you do such things by taking a chance. Of course, a boom may fall and break your neck at any moment, your books may be barred from libraries, or the camel sausage may lead to a prescription of arsenic. It's a chance you take.”

It requires that chance. It requires a risk.

In his recent book Wonder: Childhood and a Lifelong Love of Science, Frank Keil notices that pretty much all little kids are interested in science, but by adulthood most kind of drop it. Where does our inquisitiveness go? Why do we stop asking why?

Sometimes when I’m trying to understand something, I like to consider its opposite. I say, "the opposite of wonder is anxiety." My daughter says, "the opposite of wonder is lifelessness."

Curiosity can be hard to gauge in people. Only scientists with a flair for philosophy really get into it. An interdisciplinary team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, American University, and the Santa Fe Institute did a study in which they asked 149 people to browse Wikipedia for 15 minutes every day for 21 days. In tracking their browsing, they noted that each participant showed a unique “kinesthetic signature” in the way they searched for information. Amid all the diversity, two basic styles emerged: The “hunter” seeks closely related information, taking deep dives into certain topics. The “busybody,” on the other hand, jumps around, collecting information and moving on, one loose connection at a time. Sometimes, people browsed because they were trying to learn about something. Researchers called that motivation "deprivation sensitivity,” which I think is just a fancy way of saying they felt stupid. The more meandering searches tended to be more motivated by “sensation seeking”—they liked the novelty of discovery.

The same researchers hit up another group of subjects to keep diaries of when they felt curious. When participants could keep their level of curiosity pretty consistent through the day, their entire sense of well-being bloomed.

But, how closely does the science of curiosity capture the concept of wonder?

I think there’s something in the concept of wonder that invokes the miraculous, the definitionally para-scientific.

In a 1969 paper, The Philosophy of Wonder, Howard L. Parsons writes, “Wonder is distinguished from the almost purely emotional, negative experience, like panic or terror or awe. Wonder retains an element of detachment or ideation, a minimal curiosity, a control of emotion that gives psychic distance to the event and permits at least in some small degree the play of imagination.”

It seems clear that wonder isn’t the kind of curiosity motivated by feeling stupid. It lives out in a field beyond that self-consciousness or shame. Wonder lacks for panic or terror, even when the subject we’re facing is awesome.

The kids and I agree to meet for an 11 am “wonder walk,” then decide to call it a “wonder wander” a la Langston Hughes. The guidelines:

- Best not to be in a hurry.

- If you notice yourself talking or thinking about the past or the future, gently bring your attention back to the current sensory details: What you can see, hear, smell, taste, or touch.

- If you bring a phone, only use it as a camera.

- Maia reminds us that we could be in a new place or walk the route we walk every day—as long as our attention is on what we notice, we’ll always be able to wonder at something new.

We wander across Manhattan Avenue into Morningside Park, and say good morning to the turtles.

There’s something compelling about the old and the new.

Something about a church under construction.

Lit by rainbow light.

Keith Haring on the altar.

I wonder why both my kids are taller than I am.

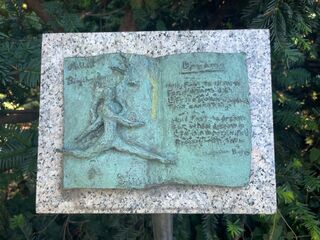

We walk through the garden without any particular direction, stop at this tribute to dreams.

It’s not until Maia starts reading that we realize it’s Hughes:

"Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go

Life is a barren field

Frozen with snow."

“Langston is walking with us,” Maia says.

Wandering.

I wonder what’s in here . . .

[Here's an expanded photo journal}