Bias

“Black Lives Matter” Matters for Children’s Development

Realities of racial oppression highlighted by BLM are keenly noticed by children

Posted December 17, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Now the policemen, they shoot at people, a Black person, because he had his hood on and if somebody didn’t do nothing, they put them on the ground or something, it’s ridiculous. (Black girl, 7th grade)

After George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis Police officer in May 2020, the rallying cry of “Black Lives Matter” resounded around the world. Peaceful marches, rallies, and protests and demands for racial justice were shared globally.

Black Lives Matter (BLM) started in 2012 as a social media hashtag in response to the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin and in just a few years transformed into a global racial justice movement. But November 24, 2014 was a watershed moment for BLM. On that day, a grand jury declined to charge the police officer who shot and killed 18-year-old Michael Brown, and in response, more than 2.4 million tweets with the hashtag #BLM flooded the cybersphere [1], marking a turnkey moment for the BLM movement.

Undoubtedly, BLM has profoundly shifted public and political discourse about race, but has it affected our nation’s children? Does BLM matter for how children understand their own racial identities? Does it matter for how we talk with children about race?

Our new paper [2], published in Developmental Psychology this month, examines the changes in children’s racial identities from 2014 to 2016. We analyzed interviews with 100 children from three racial groups: Black, Multiracial, and White. In 2014, the children were ages 9-11 years old, and we asked them about how important race is to them, what their own racial groups mean to them, and the good and not-so-good things about being a member of their racial group. In 2016, when they were 11-13 years old, we asked the same questions. We wanted to know if the meaning and significance of race changed as they grew up.

The world had changed from 2014 to 2016. The visibility of BLM surged with the National March on Washington, widespread news coverage of multiple cases of police brutality, and a highly racialized presidential election. As we listened to the interviews, we heard stories that paralleled the shifts in broader racial dialogue.

Steven is a young Black boy who participated in our study. In 2014, when Steven was a 5th-grader, he said that being Black means “You have to be smart and successful.” Race was “not important” to Steven, and he said he had never been treated differently because of race, although he had “read about it in the history stories.” These history stories were not relevant to him “[be]cause Obama became the president. Our first Black president. Stuff being changed.”

In 2016, Steven, now a 7th-grader, had matured cognitively and socially; gained new experiences and knowledge. Did his ideas about race and racial identity also change? Yes. Steven’s understanding of what it means to be a Black person, a Black boy in particular, in America changed in a significant and sobering way.

Q: What does it mean to be Black?

A: Um well, it’s hard because it’s the cops that are killing us for stupid stuff. So like, if you think like the people that are supposed to help you are killing you, then imagine life in five more years; it’s gonna be like your friends are killing you and then everybody is killing you. That’s what I feel like. So, if the cops are already killing us for doing nothin’, then you might as well just step out the door and get shot.

Q: How do you think things would be different if you weren’t Black?

A: I would get all the stuff and nobody will look at me like I was a target.

Steven has learned that being Black is no longer only about the history stories or the progress of Obama, but also about the police brutality of “right now.” It’s about the way his own body has become a target for police-sanctioned violence, about the ominous threat of racism that leaves him feeling like “everybody is killing you.” The colorblind post-racial narrative of what it means to be Black has been disrupted by the realities of racial oppression highlighted by BLM.

Steven is not the only child to tell us a narrative like this. Across the interviews, we heard a tangible shift in what and how children discussed their racial identities in the wake of the BLM movement.

I mean, like there is a thing called white privilege, I guess, and like with all the shootings and, you know, cops shooting unarmed... So yeah, definitely I think that’s [white privilege], uh, probably a thing. (White boy, 8th grade)

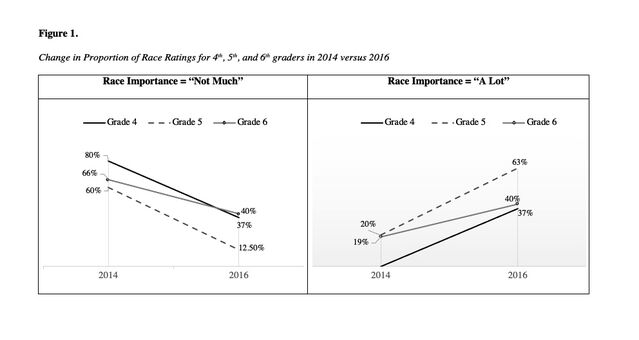

Compared to 2014, significantly more children stated that race was very important, and significantly fewer said that it was not important, suggesting that children’s overall orientation toward race had shifted.

It is reasonable to expect that 5th graders will differ from 7th graders in their thinking about race, but it is less obvious that 5th graders in 2014 should differ from 5th graders in 2016. Yet this is the pattern we observed. As shown in Figure 1 below [3], when we compared the 4th, 5th, and 6th graders in 2014 to their age-matched peers in 2016, we found that the 2016 cohort reported race as significantly more important. They were also less likely to say race does not matter, and more likely to report experiences of discrimination and racism. This change was especially notable for Black and Multiracial children in our study.

To be clear, our study does not claim that BLM is the only causal explanation for why children changed their responses about race; children develop within remarkably complex and multifaceted systems. But collectively, children told us a story that signals the importance and relevance of BLM for their development.

The well-rehearsed notions that children “don’t see color,” that they are “too young” and “too innocent” to understand race, contrasts with children’s lived experiences. Children do notice race and they experience exclusion because of it, and yet they also recognize that they shouldn’t talk about it [4]: “I can’t talk about race... and I always feel awkward to do that; we’ll just avoid that” (Black girl, 6th-grade).

Research shows that many parents, especially White parents, report “rarely or never” talking about race with their children [5]. This simply won't do. Racism is real, children notice and experience it, and we must nurture their capacity to maneuver through and disrupt it.

Below are some guiding principles for adults who wish to help young people develop healthy identities and the ability to discuss and reject the racism they encounter in our society.

Recognition: Recognize that children are thinking about race and noticing racism, and they are trying to make sense of it.

Space: Make space and pay attention. Our research consistently shows that when given a safe space and open opportunities, children can and will talk about race. Their awareness that they “shouldn’t” discuss race further underscores the need for intentional, open-ended questions that leave space for children’s wondering and noticing about themselves and the world.

Identity: Reflect on your own identity and experiences with race. What does race mean to you? How do you feel about BLM? If you are uncomfortable or fearful of talking about race, think about why. We cannot engage our children in meaningful conversations about race and support their development if we cannot address our own relationship with race and racism [6].

Intentionality: Be intentional, stay vigilant. Racism is pervasive. We must be intentional in supporting young people through this process of seeing and knowing, and disrupting the systems of racism. Silence will not resolve it [7].

In an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, Kareem-Abdul Jabbar wrote “Racism in America is like dust in the air. It seems invisible — even if you’re choking on it — until you let the sun in. Then you see it’s everywhere. As long as we keep shining that light, we have a chance of cleaning it wherever it lands. But we have to stay vigilant, because it’s always still in the air.”

The BLM movement is shining a light on American racism and our nation’s children are paying attention. The question is whether the adults are listening and if we will be vigilant about clearing the toxins so everyone can breathe.

This blog post was co-authored by R. Josiah Rosario and Chrissy Foo.

R. Josiah Rosario is a Ph.D. Candidate in Social Psychology at Northwestern University where he explores how the sociopolitical context of race and racism shape the way children, adolescents, and young adults think about themselves and their educational pathways.

Chrissy Foo is a graduate of Northwestern University and the DICE lab. Chrissy is now a healthcare consultant at AVIA, working with health systems across the country to increase patient access and equity through digital innovation.

References

[1] Milkman, R. (2017). A new political generation: Millennials and the post-2008 wave of protest. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416681031

[2] Rogers, L. O., Rosario, R. J., Padilla, D., & Foo, C. (2020). “[I]t’s hard because it’s the cops that are killing us for stupid stuff”: Racial identity in the sociopolitical context of Black Lives Matter. Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001130

[3] Rogers, L. O., Rosario, R. J., Padilla, D., & Foo, C. (2020). “[I]t’s hard because it’s the cops that are killing us for stupid stuff”: Racial identity in the sociopolitical context of Black Lives Matter. Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001130

[4] Apfelbaum, E. P., Pauker, K., Ambady, N., Sommers, S. R., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Learning (not) to talk about race: When older children underperform in social categorization. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1513. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012835

[5] Kotler, J.A, Haider, T.Z. & Levine, M.H. (2019). Identity matters: Parents’ and educators’ perceptions of children’s social identity development. New York, NY: Sesame Workshop.

[6] Anderson, R. E., Jones, S. C. T., & Stevenson, H. C. (2020). The initial development and validation of the Racial Socialization Competency Scale: Quality and quantity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(4), 426–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000316

[7] Tatum, B. D. (2017). Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?: And other conversations about race. Basic Books.