Bias

Talking About Racism With Your Teenager

Current urban demonstrations are a good cause to discuss hard social issues.

Posted June 15, 2020

Racism is commanding a lot of media attention at the moment, so naturally parents wonder what to say about it to their teenagers who are wondering what to think about it themselves.

Not a research psychologist, but an observational one, what follows just offers some ideas to help parents consider what they might want to explain and discuss with their adolescent about what is going on.

The protests

Why are these mass protest gatherings happening?

Specifically, they are to express public outrage and opposition to the deadly treatment of an unarmed black American citizen, George Floyd, by a white Minneapolis policeman, Derek Chauvin, while several other white officers looked on.

Symbolically, however, the public outcry is against something much larger—protesting historic and ongoing incidents of social mistreatment of people of color by majority-white law enforcement in America. This issue itself is seen as a smaller part of an even larger problem—majority social oppression of racial minority life in the United States.

The purpose of the current social protest is to focus public attention, organize opposition, and effect reform to address inequities in many aspects of minority life—not just in public safety, but in health, education, employment, among others. It often takes widespread anger at systematic wrongdoing to energize and effect necessary social change.

Racism

“Racism” is both a belief and a behavior. It is a belief that one race is “superior” to another. That belief becomes a behavior when it is used to justify mistreating members of the supposedly “inferior” race in inequitable and harmful ways. Racism has a lot of social and psychological and physical harm to answer for.

Racism can occur on many levels.

- Racism can be individual—personal ideas about racial superiority and inferiority one believes can influence perception. “At least I’m better than them.”

- Racism can be interpersonal—avoiding contact with an “inferior” race someone who is not of the “superior” race kind. “I don’t associate with people like them.”

- Racism can be intergroup—patrolling one’s “superior” group by keeping “inferior” people out. “We stick to our own kind and don’t let others in.”

- Racism can be institutional—where “superior” policies and procedures stop “inferior” folks from getting fairly served. “If they can’t work our system, that’s their problem.”

We/they distinctions

Racism “thinks” in stereotypes—generalizations that favorably contrast one’s superior “we” group to the inferior “they” group that is negatively characterized: “We are/They are not …”; “We know/They don’t know…”; “We care about/They don’t care about …; and so on.

Stereotypes are statements of ignorance because they blanket a whole group with a single descriptor and ignore the reality of vast individual variation among "they" as well as shared human similarities with "we." In the we/they comparison, racial stereotypes usually compliment “we” and insult “they.” Hate crimes are often motivated by stereotyping: “I wasn’t out to get him; I was out to get them!” At worst is genocide: the deliberate annihilation by "we" of an entire "they"—a classification of people based on their ethnic, racial, or religious identity.

Four acts of social oppression

Like other “isms” (sexism, for another example), racism is intended to be socially oppressive, meant to keep minority individuals down by maintaining majority dominance and control. The “We are superior/They are inferior” distinction is used to justify inequitable and even injurious treatment.

How would a person know that they were being persecuted? Consider four acts of oppression that can place one in a socially disadvantaged position.

- There is prejudice—when one is socially de-valued because of the minority category of person you are. “I’m treated as not worthy of the respect that majority people give each other.”

- There is discrimination—when one is denied opportunity because of the minority category of person you are. “I’m treated like I shouldn't be allowed what majority people are by privilege entitled to."

- There is harassment—when one is denied social safety because of the minority category of person you are. “I’m treated more suspiciously, and harshly by authority than majority people are.”

- There is complicity—when social mistreatment because of the minority category of person you are is ignored and so enabled. “By knowing but not responding, silent complicity allows injustice to carry on."

Motivation for racism

All the "isms" of oppression (racism, sexism, and the like) are variations of the one: favoritism—a system of preferential valuing and treatment that advantages some group at the expense of another. Years ago, a friend described the majority motivation for racial inequality of treatment and favored advancement of their own kind as a single question: “Who gets the social goodies?”

What characteristics have this socially selective power? In any culture, you can identify what is favored by looking at shared characteristics among the members of the ruling majority at the top of any large social, organizational, or institutional system.

In the United States, for example, socially ruling positions are disproportionately held by white males. Thus, in our workplaces, racism and sexism can affect occupational opportunity and mobility. Similarity to those at the top can influence who gets hired, who gets better treated, and who gets ahead.

Racism creates lack

Racism creates a minority group of people who can feel they lack basic rights to humane treatment that majority folks often take for granted with each other.

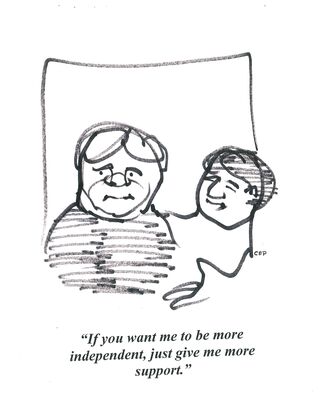

For example, at times minority can feel treated like they lack equity of standing, freedom, welcome, affirmation, safety, protection, services, inclusion, representation, responsibility, respect, dignity, trust, belief, worth, acceptance, appreciation, listening, understanding, support, sensitivity, courtesy, independence, flexibility, consideration, and fairness. These and many other interpersonal rights often feel denied or continually have to be earned.

Talk about it

Racism oppresses human lives. Racial minority people can be told and treated like:

- They are inferior

- They don’t deserve equal freedoms

- They are in constant threat and danger

- They lead lives that don’t socially matter

The current protests create an opportunity for parents and adolescents to talk about this social reality, and what might helpfully be done.