Adolescence

Helping Your Unhappy Adolescent Feel Better

Adolescence is a mixed emotional experience; parents can coach when downs occur.

Posted January 27, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

There's no getting around it: At times, growing up is an emotionally bruising business.

What with challenges from ongoing changes, chance misadventures, social pressures, and normal adversities, the journey of adolescence brings intermittent experiences of unhappiness for most young people.

I’m not talking here about debilitating states like deep despondency or abiding anxiety, for which outside help is often advisable. I mean lesser times of feeling downcast that are dispiriting to bear. “It’s felt like a really hard time!”

Now the young person often wishes she or he could find a way to emotionally recover, but may not see a way.

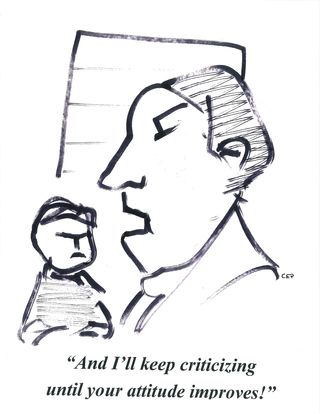

“Why don’t you cheer up?” ask the well-meaning parents trying to be helpful. The offended adolescent retorts: “I can’t just turn bad feelings off and good ones on, you know!”

That’s true. However, just because your teenager can’t alter emotions through force of will doesn’t mean she or he cannot influence feeling better, because they often can.

I believe parents have a role in teaching their teenager strategies for recovering happiness. Consider these four: finding supportive listening, using unhappiness as an instructor, positively reframing thinking, and taking rejuvenating action.

Finding supportive listening

When beset by unhappiness, the teenager does not have to keep it to themselves. Confiding in another person can help relieve some of the pain: “Talking about my hurt felt better than keeping it to myself.”

While isolation can intensify suffering, sharing with someone can ease the emotional load. Parents can tell their teenager: “If you are ever going through significant unhappiness; that is no time to go it alone. Find us or someone else to talk to about it.”

In addition, it’s usually healthier to talk out painful feelings than to act them out. Although they are good informants about experience worth paying attention to, emotions can be very bad advisors when allowed to dictate decision-making. They can tempt a person to bypass judgment and give them decision-making power in an intense moment. “I got angry, lost my temper, and did what I wish I hadn’t.”

At the very worst, despondency and isolation can be suicidal.

Parents must always monitor when their adolescent is passing through a period of unhappiness to encourage talking out and to prevent acting out.

Using unhappiness as an instructor

Sometimes the source of unhappiness, the presenting emotional problem, can suggest a solution. Since happiness is a state of felt well-being, identifying what contributor to happiness has been lost can suggest what to replenish.

“When I ran out of interests, I ran into boredom.” So develop new interests. “When I ran out of company, I ran into loneliness,” So find new companionship. “When I ran out of hope, I ran into hopelessness.” So find new objectives to look forward to. “When I ran out of acceptance, I ran into rejection.” So find other dimensions of yourself to affirm.

Thus one recovery question is: “Having run into unhappiness, how might I replenish a source of well-being that I seem to have run out of?”

Positively reframing thinking

I believe that practical psychologist Abraham Lincoln was largely correct: “People are about as happy as they make up their minds to be.” Mental sets can have emotional consequences. Thus, although feelings can be hard to directly control, they are susceptible to mental influence.

Consider the emotional power of mental sets like expectations. Expecting good outcomes may often encourage hope while anticipating bad outcomes may often provoke worry or despondency. This is why parents need not only to be help givers with their children but hope givers as well.

The reframing question is: “What am I thinking when I’m feeling unhappy, and how might changing those thoughts encourage myself to feel better?”

A young person can curse their difficulties or count their blessings, can punish their errors or learn from their mistakes, can exaggerate what happened or can put it in perspective. Their thinking can affect their feeling.

Taking rejuvenating action

Actions can also influence feelings.

For example, consider the young man who used watching favorite funny movies to feel better: “Laughing just lightens me up.” Or the young woman who had this personal practice when downcast: “I stand in front of the mirror and smile at myself and keep smiling until I start to feel happier.” Or there was the mom who explained why she liked to exercise: “Stressed from a hard day, working out at the gym restores my spirits.” Or there was the dad who explained his volunteer activities on top of his job like this: “When I do for others, I feel good about myself.”

The rejuvenation question is: “What can I enjoyably do to help myself feel better?”

So let the downcast adolescent know that while unhappy feelings can be hard to directly change, they can often be indirectly influenced: by getting a good listen, by replenishing what is needed, by positively reframing thinking, and by taking restorative action.