Health

What Do Calorie Labels Mean for America's Waistline?

Behavior change and information campaigns.

Posted April 11, 2017

In December of this year, restaurant chains with more than twenty locations will be required by federal law to post calorie information on their menus. The requirement, written into the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare), is intended to combat our country’s obesity epidemic by informing consumers how many calories are in their McDonald’s Big Macs (answer: 540) and their Subway 12-inch Italian sandwiches (answer: 860).

But if restaurants follow through, and provide their customers with calorie information, will that actually change America’s eating habits? Two recent studies try to answer this question, by taking advantage of calorie information regulations after they came into effect in several parts of the country.

A study by Jonathan Cantor and colleagues explores the impact of New York City’s calorie information requirement. New York City began requiring calorie information from chain restaurants in 2008. One of the nice things about the city’s law is that it was localized to New York, and therefore allowed researchers an opportunity to compare people’s behavior in New York City versus demographically similar locales such as Newark and Jersey City that did not have such requirements.

Cantor and colleagues surveyed people leaving one of four restaurant chains in these three cities—Burger King, KFC, McDonald’s and Wendy’s. They looked at people’s receipts to see what they’d eaten. And they administered a brief survey to see whether folks had noticed calorie information before ordering their food, and also whether such calorie information had influenced their choices.

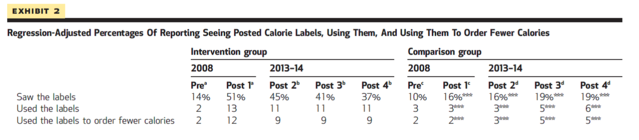

Immediately after the requirement went into effect, many New Yorkers took notice of the calorie information, with 51% saying they saw the labels before ordering their meals. In addition, about 1 in 6 folks said they factored that information into their food orders. By 2014, however, the proportion noticing such information had dropped to 37%, with only 1 in 11 factoring that information into their choices:

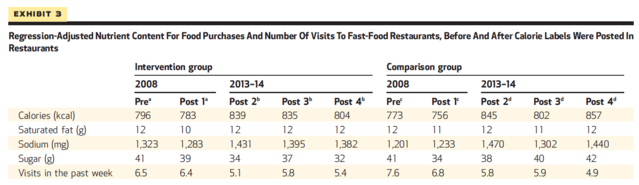

Not very promising data, I’m sorry to say. But the news is even worse than this. The researchers also discovered that calorie consumption per meal did not decline in New York City, relative to before the law passed and relative to cities without calorie information requirements:

Does that mean the calorie rule is a failure?

This is just one study, so we should be cautious about generalizing from its findings. Moreover, the study only looked at four fast food restaurants. People eating at, say, Subway—the restaurant that sells itself as being healthy—may be more responsive to such information than KFC and Burger King customers. In addition, calorie information might influence customers to shift their restaurant allegiance over time.

And maybe most importantly, calorie information might nudge restaurants to offer healthier, lower-calorie entrees to their customers. That is a finding hinted at by a study led by Sarah Bleich from Johns Hopkins University. Bleich and colleagues found that restaurants that voluntarily displayed calorie information from 2012 to 2014 offered meals with fewer average calories than restaurants that did not display such information voluntarily. No big surprise there. Why would restaurants voluntarily post information that would make them look bad? More interestingly, the researchers discovered that the new items added to these restaurants menus were, on average, even lower in calories than their already relatively healthy menus. This raises the possibility that calorie information requirements may not simply influence restaurant patrons, but may also influence restaurants.

So what’s the bottom line on how calorie information requirements influence American waistlines?

First, we don’t know. Restaurant eating behavior is too complex to easily disentangle. Some effects of calorie information requirements may be decades in arriving. Perhaps such information shifts the behavior of young people who aren’t so ingrained in their eating habits, while old fogeys like me remain stuck in our unhealthy ways. Maybe the requirements slowly change restaurant menus, reducing calorie consumption without consumers having to consciously change their behaviors. Or maybe on their own, requirements don’t do diddly.

Second, the effect of calorie count information is likely to be modest on its own, without other nudges to influence behavior. As the New York City study shows, calorie information quickly recedes into the background. To promote behavior change, we need to keep changing our nudges, to draw attention to our behavioral interventions. People are sensitive to changes in their environment. An intervention that works today may be ignored tomorrow. That’s why anti-tobacco efforts seem to shift every handful of years from one type of campaign to another. Today’s shock campaign is tomorrow’s snooze.

As a political moderate and a champion of improving consumer behavior, I think calorie information should be mandatory in many U.S. restaurants. But we shouldn’t stop with calorie displays. We need to find other, even better, ways to help translate dietary information into healthy behavior.

*Previously Published in Forbes*