Health

Housing the Homeless Could Eventually Pay For Itself

Supportive housing was associated with lower healthcare expenses

Posted June 13, 2016

A study of a supportive housing facility in Portland, Oregon, provides provocative evidence that a decent chunk of the cost of running such a facility might be paid for through healthcare savings. It might be time to give homeless people a stable home with onsite medical care.

The facility is known as the Bud Clark Commons, and it is a 130-apartment unit complex with onsite medical care, mental healthcare clinics and substance abuse treatment programs. The facility houses formerly homeless people, the majority of whom have well-established health problems, including a high rate of mental illness and/or substance abuse. This population is also known to incur high healthcare expenses, with their limited access to primary care often leading to expensive E.R. visits.

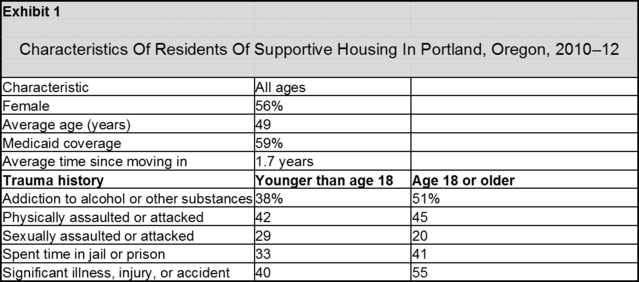

In a study published in Health Affairs, Bill Wright and colleagues from the Center for Outcomes Research and Education in Portland assessed what happened to 98 homeless people who moved into the Bud Clark Commons, a population with a staggeringly high rate of substance abuse and a disturbingly common history of being assaulted.

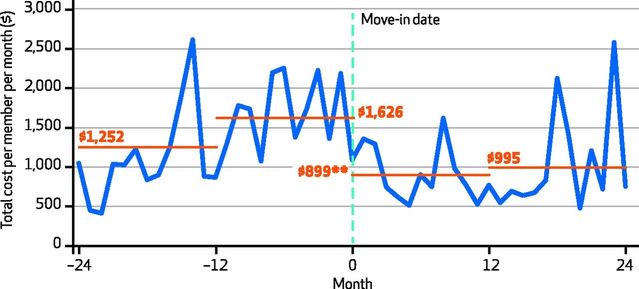

In the first year following their residency in the Bud Clark Commons, these 98 people experienced a significant drop in healthcare expenditures, a reduction that was largely sustained in the second year:

There is no way to know what healthcare these people would have received, at what cost, if they hadn’t been living in the Bud Clark Commons. The study did not report a randomized trial of supportive housing but, instead, a before/after look.

Which is why I would love to see much more research on this kind of program. And I would like to see such research assess other potential benefits of such housing, such as what impact it might have on rates of incarceration.

In the old days, we housed people with serious mental illness in asylums where we took extremes to limit their freedoms, supposedly for their own good. Then we went to another extreme, and released many of these people into the world, hoping they would thrive in their new state of freedom. Our homeless epidemic is a result, in part, of this decision to leave people with serious mental illness to fend for themselves, instead of leaving them institutionalized in asylums. Perhaps supportive housing is a better alternative to either of these extremes.

***Previously published in Forbes***