Environment

Nature vs. Nurture: Another Paradox

Our genes are what make nurture so important in determining our behavior.

Posted February 5, 2019

Dr. Claudia Gold, on a post on her Child in Mind blog, mentioned in passing that 700 new connections per second are made in the brains of newborns within the context of caregiving relationships. 700 per second!

In the nature-nurture debate about psychological behavior problems, for most of them I come down on the side of nurture being far more important than nature. Nature just provides us with a range of possible behaviors and reactions, while both nurture and thinking (don't forget about thinking) allow us to choose where within that range we would prefer to reside.

Our nature, as determined by our genes, apparently does have one all-important function. Interestingly, it is the same influence no matter what the rest of our individual genome (assuming we have intact neural functioning) contains: it dictates that we are highly likely to respond to our nurture in accordance with the feedback provided to us by our parents. Paradoxically, it is nature that makes nurture so damned important in determining our behavior.

One of the basic ideas behind my psychotherapy treatment method (unified therapy) for repetitive self destructive or self-defeating behavior patterns is that the behavior of primary attachment figures—in most cases, the parents—are, from a cognitive-behavioral standpoint, simply the most important environmental factors in triggering and reinforcing the problematic patterns. And not only when we are children, but throughout life. Certainly more powerful than a therapist can ever be.

I argue that babies come into the world completely helpless and with absolutely no knowledge about how the universe operates. We remain helpless far longer than the young of most species. Therefore, evolution likely proceeded in a way that resulted in our being biologically programmed to wire our automatic and repetitive behavioral responses in most environmental contests—in particular social contexts—in accordance with what we learn from our interactions with those attachment figures.

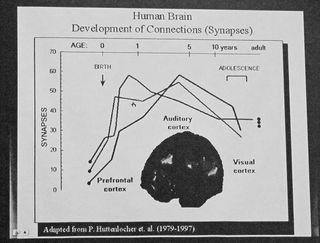

There is much evidence from neuroscience that the brain wiring that develops in this context and remains in the brain is particularly resistant to change through the normal process of neural plasticity. While it is true that later in childhood and adolescence the number of these connections is greatly reduced through a process called pruning, I suspect the ones that are lost are those that are not continually reinforced by the attachment figures.

I looked up the source for Dr. Gold’s assertion and found an article published by Harvard's Center on the Developing Child. It said that those neural connections "...are formed through the interaction of genes and a baby’s environment and experiences, especially 'serve and return' interaction with adults," which developmental researchers refer to as contingent reciprocity. These are the connections that build brain architecture—the foundation upon which all later learning, behavior, and health depend.

Serve and return was further explained: "When an infant or young child babbles, gestures, or cries, and an adult responds appropriately with eye contact, words, or a hug, neural connections are built and strengthened in the child’s brain that support the development of communication and social skills. Much like a lively game of tennis, volleyball, or ping-pong, this back-and-forth is both fun and capacity-building. When caregivers are sensitive and responsive to a young child’s signals and needs, they provide an environment rich in serve and return experiences."