Marriage

Selfishness in Marriage: "I Need ___"

Needs vs. wants—it's not just semantics.

Posted March 1, 2019

Much of marital advice is based on a view of marriage that says what we bring to the relationship is our needs. This idea is captured very well in the following quote:

“You have a right to ask for the things you need (emphasis added) in a relationship. In fact, you have a responsibility to yourself and your partner to be clear about your needs (emphasis added). You are the expert on yourself. No one else, not even your partner, can read your mind and know what you need (emphasis added) in the way of support, intimate contact, time alone, domestic order, independence, sex, love, financial security, and so on.”1

In my work with couples, I have stressed that when you are talking about the things in life that are important to you to live well, you should use the concept of “want” rather than the currently popular construct of “need.” For example, saying to your spouse, “I want to have sex with you,” is quite different than saying, “I need to have sex with you.” While you might want to argue that this is semantics, it is not.

The construct of need became popular in psychology during the middle of the twentieth century as an expression of the more general idea that we are all motivated primarily (or only) by self-interest.2 This view is not new; in fact, it has been the dominant view in psychology and in much of Western thought in general for decades. When applied to intimate relationships, it translates into the idea that we must fulfill our partner’s self-identified individual needs. (I say “self-identified” needs because there really is no way to identify a list of needs that is universally accepted.) In this view of things, we can call anything we want or prefer a need, without having to explain it.

Operating from this premise, couples are stuck with the idea that they must fulfill each other’s needs—advice that has toxic effects. These effects are:

- We are entitled to have our needs fulfilled—that’s the definition of need.

- Needs cannot be negotiated because they are entitlements; they are exchanged in tit-for-tat or quid-pro-quo arrangements (I’ll have sex with you if you will spend more time talking to me).3

- Not to have a need fulfilled is an injustice that will breed resentment and justify bad behavior.

- Valuing one another in terms of how well our self-identified “needs” are fulfilled implies that a partner has no intrinsic worth independent of how well they fulfill your self-identified needs.

- There is no end to the list of things you can need. Any want, preference, or desire can be identified as a need.

- You do not have to be concerned about how fulfilling your self-identified needs affects your partner because you believe you are entitled to have them met.

- People who promote this view tend to adopt the idea that men and women have biologically determined, different needs (e.g., men are from Mars and women are from Venus). In this view, husbands and wives must fulfill each other’s sex-based needs.

A better marriage relationship: “I want, I prefer __."

The idea of partners having things they want or prefer in order to flourish as individuals and as a couple is a better way to promote a good marriage. To have a want or preference is an expression of yourself; it is an expression of what you believe is important for you to live well, to have a good life. As such, it is important that your wants and preferences be acknowledged. At the same time, they are not demands that must be catered to. Wants or preferences are things that you value but are willing to negotiate in good faith with your spouse.

From my perspective, my wants (and associated preferences) are the best expression of who I am, so long as I carefully and critically examine them on a regular basis. My wants stem from my values, my desire to flourish, my gender, and my experience in life.

Differences between the sexes—to the degree that we know what these are—may be important in determining individual wants of husbands and wives. As wants and preferences, they can be negotiated, avoiding the risk of having gender differences create the opportunity for an unequal relationship by “privileging” male over female “need” or vice versa.

Negotiating Wants (Preferences) Collaboratively

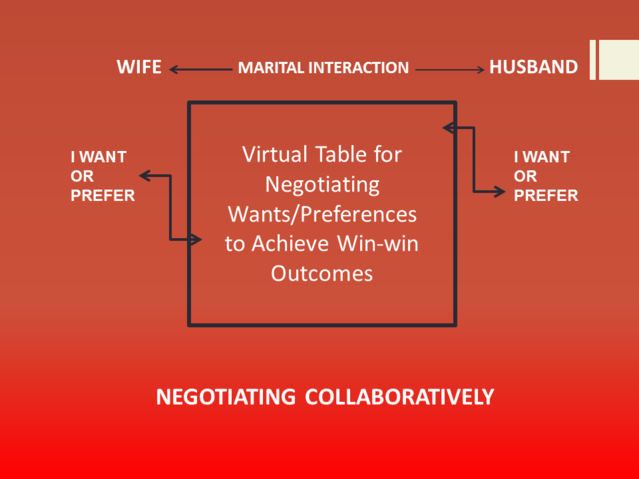

Collaborative negotiation is the ultimate form of jointly weighing your individual wants and preferences. This is the way to create a committed marriage relationship in which each of your wants is respected and honored. This schematic depicts the collaborative negotiation of individual wants.

A committed marriage is a lifelong partnership that links two people around their most fundamental wishes and wants so that the two people involved can flourish as individuals and as a couple. This requires great attention to the maintenance of a collaborative environment of negotiation.

References

1. McKay, Matthew, Patrick Fanning, and Kim Paleg. (2006) Couple Skills: Making Your Relationship Work. New Harbinger Publications.

2. Wallach, Michael A. and Lisa Wallach. (1983). Psychology’s Sanction for Selfishness: The Error of Egoism in Theory and Therapy. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

3. Psychologist John Gottman (The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work) says that good marriages should not be based on “reciprocity”—e.g., “You help me with vacuuming the house, and I’ll help out by taking out the trash.” This is often an unwritten agreement to offer something in return for each word or deed—it’s an approach to marriage that requires you to keep a running tally of who has done what for whom. Gottman argues that this kind of unspoken contract is full of anger and resentment because each partner is consciously or subconsciously keeping score. Happy marriages are not about 50/50 transactions. In happy marriages, partners find a way to share tasks and feel good about their partner and their relationship.