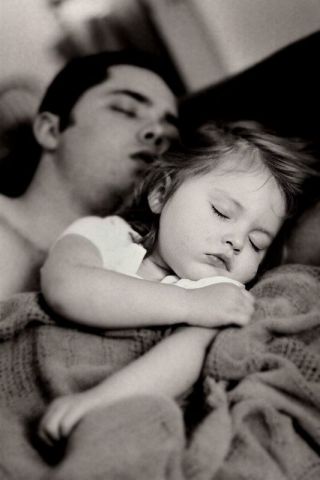

Sleep

5 Counterintuitive Ways to Get to Sleep

2. Don’t go to bed when you feel tired.

Posted February 5, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Scheduled worry time during the day can ease nighttime rumination and worry that perpetuate insomnia.

- Only go to bed when you feel sleepy—when you physically can't keep your eyes open—not necessarily when you're tired.

- Lying awake in bed is like forcing yourself to sit at the table until you're hungry. Get out of bed, work up a sleep appetite, and then return.

People with chronic insomnia experience difficulties falling and/or staying asleep at least three nights per week for three months or longer. Symptoms cause distress and daytime impairment including fatigue, mood disturbance, anxiety, irritability, and reduced quality of life, as well as difficulties with motivation and concentration. Some people struggle with falling asleep, others with maintaining it, and many with both.

Disagreement exists about how to define and quantify sleep onset insomnia—or the amount of time considered “too long” to fall asleep. Some have proffered 30 minutes while others say anything over 40-60 minutes warrants clinical attention.

But most generally agree “healthy” sleepers fall asleep within 10-20 minutes. Anything quicker raises concerns about sleep deprivation or apnea; anything longer might indicate insomnia or a circadian rhythm sleep disorder.

So when counting sheep doesn’t do it for you, consider giving these five counterintuitive strategies a try.

1. Worry (earlier).

People with chronic insomnia have a proneness to worrying—about their sleep or otherwise—especially at bedtime. Worrying is antithetical to sleep; it activates the body’s sympathetic nervous system and initiates a psychophysiological cascade of stress responses, including tachycardia and racing thoughts, keeping the body aroused and awake. But a few minutes of scheduled, daily “worry” time earlier in the day can reduce symptoms. Here’s how it works:

Schedule a 10-15 block of time in the morning or afternoon.

During that protected time, write down all the worries you can think of, big or small, in a notebook. You could stop here and feel better because simply objectifying worries can make them feel smaller (we tend to suffer more in imagination than in reality). But don’t. Instead:

Consider making two columns: one for the worries and another for the steps you could take toward mitigating them. Don’t pressure yourself to fix or solve anything — because some things can’t be fixed or solved. Instead, focus on listing one small corresponding thing you could do to make the worry less worrisome (e.g. worry: “My health”; potential step: Take a 10-minute walk today).

Rinse and repeat, modifying scheduling as needed.

The goal of the exercise isn’t to eliminate worry: it’s to compartmentalize and restrict worry so it doesn’t follow you into the bedroom. If you worry outside of your time, you can practice gently saying one of two things to yourself: either 1) “I’ve already worried about that and have a plan!” or 2) “If it’s really that important, I’ll remember it during my scheduled worry time” and move on.

With sustained practice, like a muscle that strengthens with weight training, you’ll likely notice increases in your cognitive “strength” to restrict, contain, and control worry.

2. Don’t go to bed when you feel tired.

Only go to bed when you feel sleepy, not tired. They don’t mean the same things but often get used interchangeably. Learning how to differentiate sleepiness from fatigue plays a critical role in maintaining overall sleep health.

Sleepiness describes the physical inability to stay awake—think eyelids closing, head bobbing, body feeling heavy. Fatigue describes a state of low physical or mental energy—how one might feel after a long day of work or getting into an argument with a partner (think: low motivation, headaches, low mood, difficulties concentrating and focusing).

Going to bed only when you feel sleepy (vs. fatigued) decreases the odds of spending time awake in bed because it increases the chances of falling asleep quickly and staying asleep. Combined with other behaviors, differentiating sleepiness from fatigue can prevent something called conditioned arousal.

3. Get out of bed.

People with insomnia tend to spend more time awake in bed than asleep, worrying, ruminating, and trying to sleep. Over time, the bed morphs into a cue for wakefulness, anxiety, and frustration—a phenomenon known as conditioned arousal. Conditioned arousal perpetuates insomnia. Stimulus control targets this conditioned arousal to help people with insomnia relearn the bed as a place for sleep, not for wakefulness. To practice stimulus control:

Step 1: Get out of bed if you’re unable to fall or return to sleep. To unlearn the association of the bed with wakefulness and restore the association of the bed with sleep, get out of bed when attempts to sleep feel effortful, frustrating, or anxiety-provoking, after about 15-30 minutes. No need to clock-watch: As soon as you start noticing these symptoms, get out of bed. Only return to bed when you feel sleepy, not tired.

You can think about it like hunger: If you didn’t feel hungry, you probably wouldn’t sit at the table waiting for it. Instead, you’d probably walk away, go work up an appetite, and return once you felt hungry. You can think about your bed and sleeping in it in the same way.

Step 2: When you get out of bed, go into another room—with the lights off or low—and do something relaxing, not stimulating. Find what works for you but refrain from drinking, smoking, or doing anything vigorous like exercising.

Planning ahead and making the activity pleasant can help. Some options may include: practicing a relaxation exercise, meditating, sketching or working on a puzzle. Return to bed only when you notice the symptoms of sleepiness return. Rinse and repeat as necessary.

Other general best practices: Use the bed for sleep and for sex only. Everything else should happen outside of it.

4. Warm up.

The thermal environment plays a major role in governing human sleep. Like light, core body temperature works as a zeitgeber (“time giver”) to synchronize our circadian rhythm or our internal clock. To initiate and maintain sleep, the core body temperature needs to drop by 2-3 degrees Fahrenheit.

Emerging evidence suggests passive body heating with a warm bath or shower 60 to 120 minutes before bed can hasten sleep onset for this reason. While it may sound counterintuitive, taking a bath or shower just before bed elicits heat from the body’s core to the surface, thereby cooling the body.

Integrating passive body heating into a broader bedtime ritual/protocol one hour before your habitual sleep time can optimize sleep health as well as prevent and manage insomnia symptoms. Just like a car that must decelerate before turning a corner, your body and brain require time to down-regulate before going to bed. Combined with passive body heating, dimming the lights, and doing something relaxing but not stimulating about an hour before you usually feel sleepy can promote sleep onset.

5. Try not falling asleep.

What do you notice when you’re asked not to think about a white bear? Probably a white bear. This demonstrates how active thought suppression usually increases the frequency of undesired thoughts or behaviors. Similarly, the common preoccupation with trying to fall asleep among people with chronic insomnia can keep them awake.

Paradoxical intention (PI), an intervention for sleep onset insomnia, leverages and flips this insight—encouraging patients to attempt to stay awake to eliminate the pressure associated with falling asleep.

By eliminating voluntary sleep effort, PI minimizes sleep performance anxiety, hastening sleep onset. It also diverts attention from sleep performance, promoting cognitive de-arousal and relaxation. Consider trying the following PI methods:

- Instruct yourself to “stay awake” tonight (though, of course, the goal isn’t to run around and keep yourself awake.

- When your eyelids feel like they want to close, say to yourself gently: “Just stay awake for another few moments. I’ll fall asleep naturally when I’m ready.”

- Lie comfortably in your bed with the lights off, but keep your eyes open (an exposure exercise, this helps teach patients the non-catastrophic implications of staying awake).

- Give up any effort to fall asleep.

- Give up any concern about still being awake.

- Adopt a mindset of not expecting anything.

- Ask yourself what a good sleeper would do. Nothing. Good sleepers don’t think about sleep and don’t do anything specific to help them sleep.

- Don’t purposefully make yourself stay awake, but if you can shift the focus off attempting to fall asleep, you will find it unfolds naturally.

The more you try to do one thing (stay awake), the more the opposite may happen (fall asleep).

PI’s effectiveness as a standalone intervention remains unclear but probably works best when delivered as part of multicomponent cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), the gold standard behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia.

Frontloading worry, differentiating sleepiness from fatigue, practicing stimulus control, implementing a bedtime ritual, and experimenting with paradoxical intention techniques may help you to dream sweeter dreams, sooner. But if you experience chronic issues falling and staying asleep, and those issues interfere with daytime functioning, talk to your doctor. A referral to a behavioral sleep medicine provider may help.

Facebook image: fizkes/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Pixel-Shot/Shutterstock

References

A version of this story also appears on: https://medcircle.com/articles/how-to-fall-asleep/