Personality

Wills and Ways: Changing Your Personality

Thinking about the necessary ingredients to become a better you.

Posted January 21, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- There is increasing evidence that we can change our personalities.

- Personality change is best achieved via changing its components in a specific, concerted manner.

- Personality change need not always be self-directed.

We have reached the time of the year when we think about ourselves. Not everyone makes explicit New Year’s resolutions or feels any differently about anything when the calendar changes over, but enough people do that probably everyone, at least briefly, considers the concept of intentional change for the better. As a personality psychologist and professor, probably the most common class of questions I get pertains to personality stability. Can we change? How? When? There are numerous brilliant minds working on these problems, and a full inquiry is too voluminous (and requires more nuance) than this space or my expertise allows (tentative answers: yes, many potential mechanisms, all the time).

But I wanted to discuss a very specific form of change in this post: intentional trait change. A personality trait is a characteristic pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting that distinguishes one person from another. In natural language, traits often show up as adjectives used to describe one’s personality (e.g., friendly, recalcitrant, creative, bold, petty, loquacious) and imply a degree of stability. When you tell me that Fred is quiet, I expect that when I meet him he will speak infrequently or softly or both. And I expect that this is driven internally—Fred’s quiet behavior is carried with Fred wherever he goes and manifests itself in a variety of circumstances. But what if Fred doesn’t want to be quiet anymore? What if Fred prefers to roar? Can he make this happen? Should he hire a coach?

Over the past half decade or so, psychologists (led frequently by Nathan Hudson) have been considering this question in earnest. Early results are generally promising, and sometimes in surprising ways. First, across major (Big Five) trait dimensions—with the interesting exception of Openness to Experience—students who wanted to change a given trait over a 3-month period were generally successful in doing so, at least from their own perspectives (Hudson & Fraley, 2015). Further, these changes could be at least partially traced to changes in behavior, such that logs the participants kept demonstrated changes in behaviors that preceded changes in self-perception.

But how did they do it? It turns out it was more effective to have relevant goals prescribed to some degree rather than to allow people to identify their own change mechanisms. Often, we know the endpoint (“I’d like to be more responsible”), but are less equipped to identify sensible intermediate steps (“I’ll start waking up a half-hour earlier each day to do something productive”). As such, change plans were more successful when participants received some instruction to develop small, concrete intervening goals (e.g., organize the app icons on your phone’s home screen [Conscientiousness], smile at someone you don’t know [Agreeableness]). In fact, there was some evidence that without such coaching, the intervention could have effects opposite of the intent: one might come to see oneself as, say, less emotionally stable when the goal was to enhance this characteristic.

Why would this happen? The authors report that people’s desire for change seems to be relatively uniform, and they suggest that vague (and thus perhaps less obtainable) goals (e.g., “be more positive,” “meet new people,” etc.) may create circumstances wherein one is essentially repeatedly faced with their own failure to achieve change, and thus begins to believe that they are even worse off than they initially thought. For example, someone who would like to more emotionally stable may develop a goal to relax when they’re stressed. But if each week you’re asked to recall instances when you relaxed in the face of stress and cannot find any, the belief that you’re unable to regulate your anxiety may grow stronger, altering your fundamental self-perception for this trait.

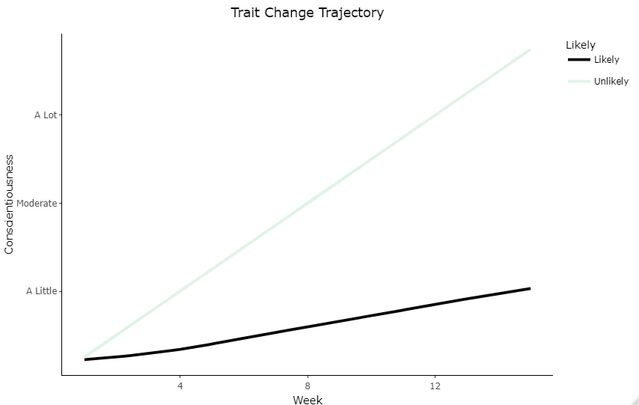

You might ask yourself whether all this is to be believed, given that all information is coming from one source—the person themselves. Is it possible that people say they want to change, then say they do different things, then say they’ve changed? Sure. And future studies employing peer reports of personality and behavioral change would certainly bolster these findings. That said, there are some reasons to believe that these changes aren’t all in our heads. For instance, in a more recent study, Hudson (2021) asked people to identify change goals for a specific trait but subsequently randomly assigned people to different change protocols. For example, I may have stated that I want to become more conscientious, but I received an intervention aimed at increasing my emotional stability. It turns out that changes occurred in correspondence with the intervention, even without the explicit preference for a change in that domain. One caveat here is that this manner of intervention was only tested on Emotional Stability and Conscientiousness, and only worked in one case (Conscientiousness). Further, this does not mean that you can induce get-up-and-go in your lazy cousin through sheer force of your own will, but it might mean that presenting people with challenges that are consistent in nature over time might help them change, even without their desire for that specific change.

So how does it all work? Essentially, there are two competing accounts of how trait change occurs in individuals. One (the Sociogenomic account) posits that small changes in behaviors or emotional states accumulate in ways that directly lead to changes in personality and are mediated biologically—simply doing things, by choice or by external force, changes the way we interact with the world in ways that don’t require consideration of self-perception as part of the process. The other (Neo-Socioanalytic) account suggests that conscious attempts to change self-perceptions work not only to create the molecular state changes but also that these motivations to change affect self-perceptions or identity, which in turn affect personality. The former account would be a tidy way to explain that conscientiousness seems to be changed without the person’s knowledge or investment, but the latter account would be supported by successful changes to Emotional Stability only occurring when the individual has willfully chosen to change and is participating faithfully in the process.

So…About that Resolution

Regardless of the mechanism, there seems to be good news for you if changing an aspect of your personality is on your list. Obviously, some traits will be easier to change than others, and it’s important to note that these changes aren’t dramatic (our quiet friend Fred is unlikely to actually roar), nor are we sure that they would persist if and when your intervention lapses. But in three months, you could be more extraverted or more conscientious than you are today, provided you set clear, consistent, relevant subgoals.

The other day, my students asked me about my greatest weaknesses, and as I mentally scrolled through the prodigious list, one thing that stuck out to me was that I’m not great at enjoying myself or celebrating in general. So, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go write down some good things that happened today to share with my friends and loved ones, prepare to vigorously praise some preschool artwork, and think about some little fun things to do next week. It's going to be a good year.

References

Hudson. (2021). Does successfully changing personality traits via intervention require that participants be autonomously motivated to change? Journal of Research in Personality, 95, 104160–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104160

Hudson, & Fraley, R. C. (2015). Volitional Personality Trait Change: Can People Choose to Change Their Personality Traits? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 490–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000021