Mindfulness

Did I Already Do That?

Mindfulness is more than meditation

Posted May 24, 2021 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Technology allows people to do multiple tasks at a time; how effective they are is something else.

- Mindfulness goes way beyond meditation, and cultivating mindfulness aids retention of information.

- Mindfulness begins with quieting the inner critic, which enable people to maintain focus and attention.

- Start by making a compliment sandwich.

We’ve all done it. Going through the motions of showering in the morning and not remembering whether you shampooed before you put in the conditioner. Meeting someone new, engaging in a whole conversation but unable to remember the person’s name afterward. Driving somewhere and then wondering how you got that far.

Our brains are amazing machines, capable of countless thoughts and processes every second. As technology has advanced, the number of things we can do at the same time has increased. We can watch TV and play a game on our tablet. We can listen to an ebook or music while we drive. We can participate in a video conference and answer email. Some people can do more than two things at the same time—how effectively is up for debate. But all this multitasking takes a toll on what information we retain and how well we retain it.

When people talk about mindfulness they tend to describe it as being aware of things in the present moment and looking at the world around you as well as your own thoughts in a nonjudgmental way. Mindfulness has been popularized by talk shows, self-help books, and even apps. And while these presentations teach mindfulness in the moment, they don’t really address how to make mindfulness a habit outside of the time you might spend meditating.

When we meditate, we try to suppress our internal dialogue—we may begin to think about a sound in a different room or what we want to do after work. Mindfulness practice teaches us to look at those thoughts with curiosity but to not focus on them. If we can’t fully clear our minds, we can at least not get drawn down a rabbit hole of thoughts.

However, mindfulness is more than meditation, and there are ways we can train our minds to be more mindful as we navigate our day to day. One of the keys to developing this kind of mindfulness is to harness our internal dialogue. We all have that voice in our head that tells us: “You shouldn’t have said that.” “Why didn’t you say…?” “First, I need to get coffee, then go to the dry cleaners, and maybe after that…”

Many people subconsciously use this metacognitive conversation to criticize themselves, often harshly. At the very least, we use the conversation to evaluate our behavior and actions. Making a concerted effort to make this conversation more positive can help with our day-to-day mindfulness. We can do this by making a conscious effort to compliment ourselves—even if it’s just recognizing that we found fault with what we did—rather than just criticizing ourselves for the behavior.

I describe this as a compliment sandwich; for every critical thing your inner voice says, you should get in the habit of making sure that there are two compliments in there as well. Besides making you feel good and focused, this compliment sandwich can help you reduce stress. Stress has a negative impact on neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, so a more positive inner conversation can stimulate the development of new neuropathways.

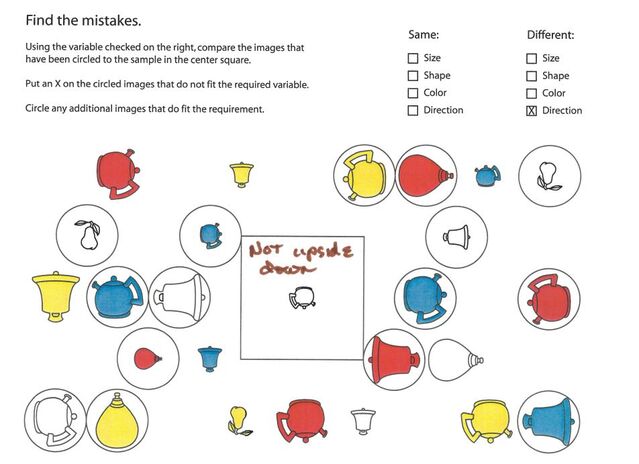

In my practice I use exercises to get participants to use their inner dialogue to maintain focus and attention. For example, in this first exercise, the participants are asked to identify the mistakes on the page using just one variable: Direction.

Looking through each of the pictures, the participants need to determine which objects are not upside down. By focusing on just one variable, the participants can concentrate on determining the orientation of each object.

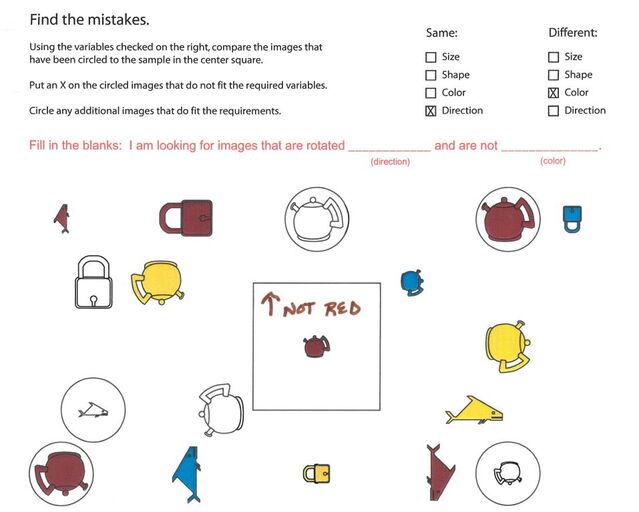

As we increase the number of variables, the participants must be able to hold multiple criteria as they evaluate the exercise. In this next exercise, the participants use two variables: direction and color. They need to determine which objects are oriented upright and are NOT red. In addition to having two variables, one of the variables is a negative—not red. This increases the complexity of the metacognitive conversation.

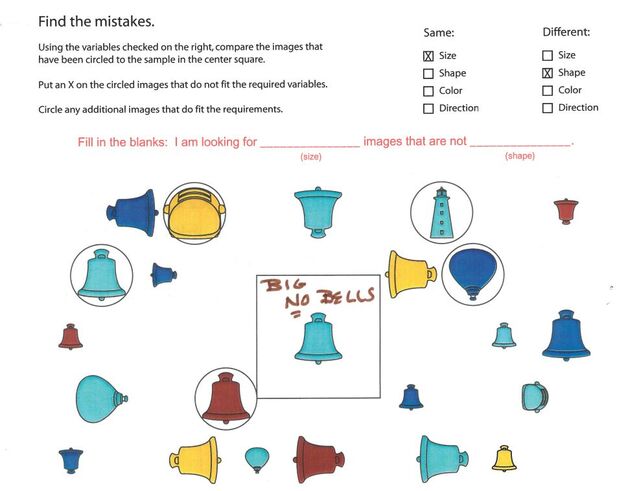

In this next exercise, we still have two variables: size and shape, which pose a further challenge. Color or its absence tends to be easier as a variable. But in this case we don’t care about color, just size and shape.

Increasing the number of variables is like increasing weights when you go to the gym. When you first begin, 5 pounds might seem difficult. As it gets easier you might increase the number of reps. When the number of reps gets easier, you can increase to 10 pounds, etc.

To complete these exercises, we must use our internal dialog to direct our focus and to maintain mindfulness. By learning to control our internal dialogue, we can reduce stress, enhance working memory, negotiate ambiguity, assess different perspectives, ensure goals and intentions align, and finally, stay focused and mindful.