Charisma

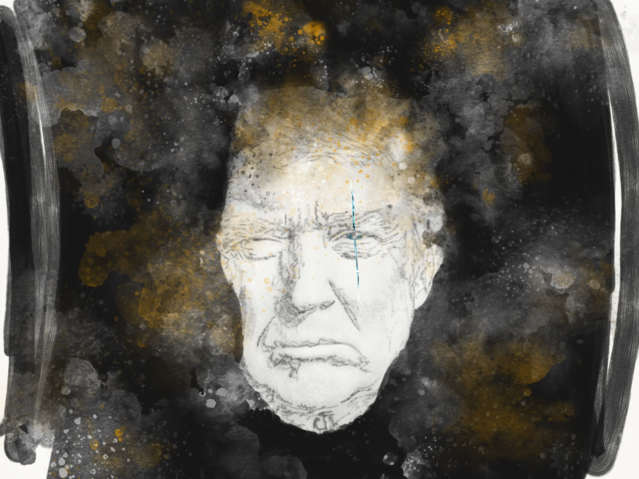

Should Charismatic Leaders Come with a Warning Label?

The reality we must face about charismatic leaders.

Posted March 24, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Is there anything more terrifying than a sea of faces, nodding like drones, drooling at the mouth as their chosen speaker is delivering a feel-good speech? With the upcoming presidential election, serious questions about the role of charisma and popularity need to be addressed.

Psychologists have spent well over a hundred years attempting to understand why, as a collective, we can be persuaded to do awful things. Over the most recent decades, there has been an attempt to become increasingly sophisticated and nuanced in trying to explain this phenomenon. Forget obedience to authority, or mass contagion, let us instead talk about leaders oozing with charisma.

In a previous article, I highlighted how Milgram's infamous obedience to authority studies actually demonstrate less of a willingness to mindlessly obey an authority figure, and more of an ability to persuade an individual using charisma. When you get right down to it, Milgram's studies showed that arguments designed to convince and persuade seem to have more effect at eliciting a response from the participant than forced obedience by the experimenter. Indeed, the experimenter actually elicited obedience without a rigid order, and when a direct order was given, obedience failed.

Truthfully, knowledge about the dangers of charismatic leaders has been in the public zeitgeist for decades. A soon to be motion picture based on the critically acclaimed, bestselling sci-fi novel of all time, Dune, explores the dangers of developing a cult around a messiah-like figure to "save" people. Back in the 1950s, the author stated:

“I wrote the Dune series because I had this idea that charismatic leaders ought to come with a warning label on their forehead: May be dangerous to your health."

His books follow the rise and fall of such leaders and the horrific damage done to humanity when a cult of personality attempts to control the destiny of mankind. Herbert’s warnings appear to be directly connected to American Presidents:

“I think that John Kennedy was one of the most dangerous presidents this country ever had. People didn't question him. And whenever citizens are willing to give unreined power to a charismatic leader, such as Kennedy, they tend to end up creating a kind of demigod...or a leader who covers up mistakes—instead of admitting them—and makes matters worse instead of better. Now Richard Nixon, on the other hand, did us all a favor...Nixon taught us one hell of a lesson, and I thank him for it. He made us distrust government leaders. We didn't mistrust Kennedy the way we did Nixon, although we probably had just as good a reason to do so.”

The rise of the charismatic president to propel a 'movement' appears to be an upward trajectory. When researching the awe struck effect, researcher Jochen Menges attended an Obama speech, during this charismatic speech of hope and unity, Menges noted feeling "warm" and "mesmerised." However, to his surprise upon scanning the crowd, there were not expressions of smiles or excitement, but frozen faces simply staring. This emotional suppression observed by Menges (throughout a series of studies) is posited to absorb mental resources typically used for memory and cognitive performance. As such, according to Menges, the audience member is less able to make critical decisions, leaving them far more vulnerable to individuals who wield power.

When listening to a speech delivered by the highly charismatic Obama, Megnes turned to a member of the audience and asked what it was about Obama's speech they liked. That person could not identify coherent, reasoned arguments, only a sense or feeling of memorization. Replicating this in future studies, participants scored poorly when recalling key points to a message from a charismatic leader and did significantly better when the same speech was delivered with a "normal" voice. Chillingly, the charismatic group thought they heard the message and processed it, whereas in fact they only felt it. They could not distinguish between feeling the speech and cognitively processing the speech.

With heavy doses of charisma and a deadly drop of envy, leaders such as Castro and Hitler inspired millions to turn their anger and desperation toward an outgroup as a means of control. If people are susceptible to persuasion during difficult times, and a charismatic leader can so readily turn off the thinking part of one's brain, without knowledge of the audience, what dangers does that breed in an uncertain age of populism? Certainly, it does not appear that democracy shields humans from such folly. Charisma appears to be a trend within the American presidency. JFK, Reagan, Clinton, Obama and Trump, like them or not, are all considered more charismatic than their opponents.