Fear

Alan Robert and the Healing Power of Horror

A visual artist and musician finds purpose in fear.

Posted February 18, 2021

“Well, I’ll bleed on through the night

I suppose I’ll be dead by the morning light

So, don’t be surprised if you mind when you find me.”

–From “River Runs Red” by Life of Agony

Can horror be healthy?

My first instinct is absolutely not. That may be because I don’t tend to enjoy more conventional forms of fear-inducing activities. Roller coasters? Hate them. Bungee jumping? Not interested. Skydiving? No thanks. And generally, whenever I’ve tried watching “horror” movies, it didn’t go well. The Exorcist (1973) made me fear the entire supernatural realm. The Shining (1980) ruined snow and people who dressed up like animals for me. And Jaws (1975) guaranteed that the ocean was permanently less enjoyable. These experiences feel triggering rather than soothing.

And yet I absolutely love darker, more intense, and more frightening forms of music and art. For example, I love all things zombie—from AMC’s The Walking Dead to 28 Days Later (2002). And while many people find the content, style, and imagery of extreme heavy metal to be “horrifying”—I often find it soothing. Taking it a step further, I often find the musicians and artists who produce these forms of art to be anything but frightening. Rather, they tend to be quiet, contemplative, and empathic people who seem to be willing to grapple with difficult issues faced by themselves and the world. Overall, this art and the people involved make me feel validated and understood—that it is OK to have darker thoughts and emotions.

In fact, research suggests that the potential for horror genres of film, art, and music to improve well-being may not be so outlandish. For example, one recent study of 310 participants found that people who enjoy horror or “prepper” genres (e.g., alien invasion, apocalyptic, or zombie) films tended to show higher “resilience’ in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, one study of extreme metal music found that, like me, fans of the music demonstrate physiological responses to the music that indicate increased calm and lower stress. Further, one study found that people who identified as “metalheads” during the 1980s later became happier and more well-adjusted than their decidedly less metallic peers.

The stakes are high as research suggests that both art therapy and music therapy can have significant mental health benefits. Thus, understanding the potential benefits of more extreme forms of art and music in helping people cope with trauma, depression, and addiction offers possible avenues for helping people treat their mental illnesses.

Can horror help us heal?

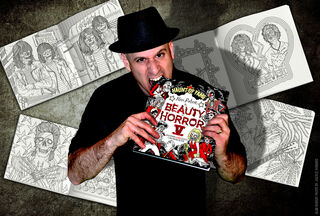

I took this question into my conversation with artist and musician Alan Robert for The Hardcore Humanism Podcast. Robert has distinguished himself in two forms of horror-related art forms. He is the bassist and songwriter for the heavy metal band Life of Agony, whose album River Runs Red was rated as one of the greatest heavy metal albums of all time by Rolling Stone. Also, he is a lifelong horror buff and the author and artist behind the best-selling Beauty of Horror coloring book series, including the upcoming fifth book in the series, The Beauty of Horror V: Haunt of Fame.

And I arrived at the conclusion that I was asking the wrong question. Perhaps the more appropriate question is not “whether” horror can be healthy or healing, but rather “how” horror can be healthy for those who enjoy and embrace the genre. And based on the discussion with Robert, I concluded that what determines the therapeutic value of horror is not how we passively experience the genre, but rather our willingness to actively connect with and engage with the material—that gives it its true potential healing power.

One metaphor I considered when trying to understand Robert’s connection to horror was likening it to a form of therapy. A factor that may make a particular form of therapy effective is whether the client/patient buys into the overall theory and therapeutic technique in question. At an early age, Robert seemed to have a preternatural ability to connect to horror. He recalled the first time he was able to watch Amityville Horror (1979). Even though he ran out of the room in fear, he still managed to listen to the movie and found he connected to the music. “I listened to the whole movie through the wall,” Robert told me. “... But my imagination took over and listening to the sounds and the sound effects and the music was scarier than anything I could imagine.”

In fact, as he got older, the connection to horror in film and music grew as he discovered that being a horror or metal fan was less common. It became a badge of honor to engage in art forms that were more underground and less widely accepted. “What made horror cool growing up as a kid was there were no stars in there. It's not like, ‘Oh, there's that actor—I gotta go see that movie.’ It was like all unknowns. And they were kind of low-budget films. And fans of those movies, you know, really attached themselves,” Robert recalled. “It was like something special that only I know about this. ‘You never heard of that movie? Oh, you’ve got to go to the video store and find out.’ Same thing with metal, you know, ‘I got the Metallica No Life ‘Til Leather demo. Have you heard it yet?’”

The next factor that tends to make a particular therapy work is that there are concrete actions that can be taken to facilitate the therapeutic process. For example, the actions can be actively listening to and talking with a therapist or learning different forms of cognitive and behavioral coping—there’s something a person can do to practice the therapy to deepen its effects.

Similarly, in Robert’s experience with horror, he went from actively watching horror to using it as a vehicle to create art. He maintained his connection to the material by drawing the characters he saw from memory. “The visuals and the feeling that I got from watching them inspiring me to create artwork. And that's something that has never left me, you know,” he recalled. “And as I got better as an illustrator, I would go into my own realms of horror stories and characters, inspired by the things that I loved growing up.”

The third thing that we often need for a therapy to work is seeing real-world results. Robert first saw results when he realized that his art could help him gain popularity among his peers. “I was always the kid at the school lunchroom table drawing in my note pad, crazy monsters and whatever came to my mind,” he said. “And a lot of kids would circle around to see what I was doing. … And that's how I made a lot of friends in school—just by drawing and people would check it out.”

Soon Robert discovered that art could be a business as well. As a heavy metal fan, he was drawn to the gory horror-movie images of bands like Iron Maiden and its unofficial mascot “Eddie The Head.” Little did he know that this would be the beginning of his professional development as both a visual artist and eventually a musician. “In the '80s, if you remember, especially in the metal scene, everyone had denim jackets that were painted with the album covers on the back. And, you know, at 16 I was making loot man. I was painting Eddie all over the place … it turned into like a little business,” Robert explained. “I think that's almost how I got into metal too. Because between the visuals of Kiss and Iron Maiden—I didn't even know what Iron Maiden sounded like, I just bought it because of the album covers. And I would draw them on my notebooks and stuff. And it just happened that they wrote kick-ass music at the time, too. And that's, it was kind of a meld of my favorite things, scary imagery with cool music.”

As time went on, Robert found that his initial interest in horror opened him up to being connected to the world in general. And to this day he uses his art as a way of healing—of processing his emotions and being open to the world. “I think it's just like certain things, whether it's movies, or music, or certain pieces of art, inspiring me to be creative. And then my emotions, or whatever comes out through those different channels … I almost feel like people that do creative work, have an antenna. And when that antenna's up, and you can kind of pull in certain pieces of energy, it can channel through you,” Robert explained. “… Ultimately, my passion for horror and music opened doors for me in life-changing ways and put me on a path …

“I can’t imagine my life without either one.”

References

You can listen to Dr. Mike's conversation with Alan Robert on the Hardcore Humanism Podcast at HardcoreHumanism.com or on your favorite podcast app.