Media

Animal Cruelty Does Not Predict Who Will Be A School Shooter

The idea that most school shooters have a history of abusing animals is a myth.

Posted February 21, 2018

Nikolas Cruz, the 19 year-old who methodically killed 17 people at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida had a history of animal cruelty. He posted pictures of dead animals on social media, he shot squirrels and chickens with a pellet gun, he jammed sticks into rabbit holes, he killed toads. This is not a surprise. Other school shooters also abused animals. For instance, both Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Columbine, Colorado shooters, boasted of mutilating animals. And Kip Kinkel who murdered his parents before killing two people and wounding 25 others in a high school in Springfield, Oregon was said to have mutilated a cow and to have stuffed fire crackers into the mouths of cats.

Tragically, a school shooting occurs about once a week in the United States, and researchers are desperately looking for warning signals that can identify potential perpetrators. A history of animal cruelty is often touted as one of these red flags. For example, in the wake of the Parkland shooting, a headline in the New York Daily News proclaimed “More animal abuse scrutiny could stop killers like Nikolas Crus.”

It would great if we could reduce or even eliminate school massacres by screening children and adults for animal cruelty. But we can’t. Here are three reasons why animal abuse is not a good predictor of who will become a school shooter.

Reason 1. There is a surprisingly weak relationship between animal cruelty and human-directed violence.

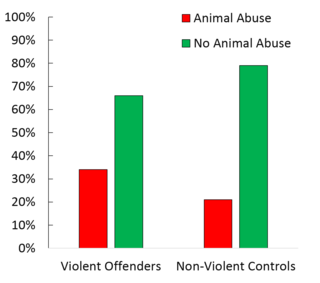

To understand rates of animal abuse among school shooters, we first need to examine the strength of the link between animal cruelty and human-directed violence. Many investigators have compared rates of animal abuse in violent criminals and in people with no history of violence. In 2016, Dr. Emily Patterson-Kane used a statistical technique called

meta-analysis to combine the results of 15 of these studies. She found that 34% of violent offenders had a history of animal abuse. But so did 21% of non-violent individuals in the control groups. Patterson-Kane concluded these differences in abuse rates were, from a statistical point of view, real but small. Indeed, she is more impressed with the fact that most people who commit violent crimes against humans do not have a history of violence directed at animals.

Further, animal cruelty is surprisingly common in “normal” people. For example, studies have found that nearly 30% of college students admit to having committed some form of animal abuse. Indeed, in a recent paper, the psychologists Bill Henry and Cheryl Sanders concluded “Some participation in animal abuse may be considered normative in American males.”

In short, most violent criminals do not have a history of animal abuse, while a large percentage of apparently normal people do.

Reason 2. Most school shooters do not have a history of animal cruelty.

Thanks to the media and publicity by animal protection groups, the idea that nearly all school shooters are animal abusers is widely accepted by the public. But while it sounds good, this claim is not true. Researchers have investigated the incidence of animal cruelty among school shooters. Here is what they have found.

- A joint task force of the U.S. Secret Service and the Department of Education reported that only 5 of 37 school shooters had a history of animal abuse. The committee concluded, “Very few of the attackers were known to have harmed or killed an animal at any time prior to the incident.”

- A 2003 study found that perpetrators had a history of animal cruelty in only 3 of 15 school shootings committed between 1995 and 2001.

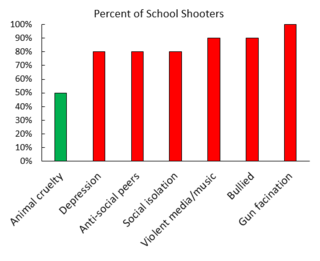

- Pacific University researchers examined risk factors associated with 10 school shootings. As shown in this graph, they found that 50% of the shooters had a

Source: Graph by Hal Herzog

Source: Graph by Hal Herzoghistory of animal cruelty. However, other risk factors were much more important. Among these were depression, bullying, social isolation, preoccupation with violent music or media, and a fascination with guns.

But the most thorough study of the relationship between shootings and animal cruelty was a 2014 investigation by Arnold Arluke and Eric Madfis. They studied both the frequency and form of animal cruelty among 23 young perpetrators of school massacres that occurred between 1988 and 2012. Unlike prior studies, they examined the actual types of animal abuse committed by the shooters.

Consistent with other studies, they reported that most of the shooters (57%) had no history of animal cruelty. They did, however, find that the types of cruelty committed by the perpetrators who were animal abusers were often different than the cruelty committed by “normal” animal abusers. In nine of the ten cases, the animal abuse was “up close and personal.” That is, the acts involved hands-on direct contact with the animal. Indeed, only one of the school shooters had used a method of torment which did not require touching the animals. In seven cases, the abuse was directed at dog and cats. But in no case did the animal cruelty involve the shooters' personal pets or even animals in their neighborhood.

But here is the big surprise. Arluke and Madfis found that four of the school shooters had a record of pronounced empathy and affection for animals. Sandy Hook Elementary School killer Adam Lanza, for instance, apparently became a vegetarian because he did not want to harm animals. And Charles Andrew Williams who killed two classmates and wounded 13 others became extremely upset when one of his friends killed a frog. Williams would keep field mice as pets and even have little funerals for them when they died.

Reason 3. "Link" logic is flawed.

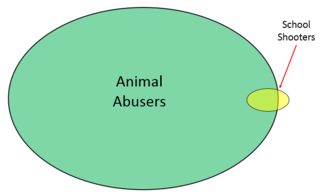

The final reason that screening for animal abuse is unlikely to make a dent in school shootings boils down to a fundamental principle you may remember from Logic 101: “All A’s are B’s does not mean that all B’s are A’s.” This point is illustrated in this Venn diagram, and it plays out in lots of ways in social issues.

For example, just because most heroin addicts start out with cigarettes does not mean that most cigarette smokers will become junkies. And just because most dog attack deaths in the United States are attributed to pit bulls does not mean that most pit bulls are dangerous. It’s the same with school massacres and animal cruelty. Indeed, even if ALL the school shooters had a history of animal abuse, we could not conclude that most animal abusers, including those of the "up close and personal" variety," are likely to walk into a school with a gun. The truth is that, at some point in their lives, millions of Americans have mistreated an animal. By comparison, there is only a relative handful of school shooters.

The Bottom Line

School massacres are an unspeakable tragedy. But increased scrutiny for animal abuse will not make them less frequent. There are plenty of reasons we should be concerned about animal cruelty, but preventing violence in our schools is not one of them.

References

Arluke, A., & Madfis, E. (2014). Animal abuse as a warning sign of school massacres: A critique and refinement. Homicide studies, 18(1), 7-22.

Henry, B. C., & Sanders, C. E. (2007). Bullying and animal abuse: Is there a connection? Society & Animals 15, 2:107-126.

Leary, M. R., Kowalski, R. M., Smith, L., & Phillips, S. (2003). Teasing, rejection, and violence: Case studies of the school shootings. Aggressive Behavior, 29(3), 202-214.

Patterson-Kane, E. (2016) The relation of animal maltreatment to aggression. In Animal Maltreatment: Forensic Mental Health Issues and Evaluations. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 140 - 158.

Verlinden, S., Hersen, M. & Thomas, J., 2000. Risk factors in school shootings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(1), 3-56.

Vossekuil, B., Fein, R. A., Reddy, M., Borum, R., & Modzeleski, W. (2002). The final report and findings of the Safe School Initiative. Washington, DC: US Secret Service and Department of Education.