When Healing Is a No-Brainer

By relying on the human penchant for mental shortcuts and social influences, scientists find they can tap directly into the mind's tremendous ability to heal the body. But first they have to get the rational brain out of the way.

By Samuel Paul Veissière Ph.D. published July 4, 2017 - last reviewed on July 14, 2017

On May 14, 2013, Angelina Jolie announced that she would undergo breast removal surgery to prevent cancer. The decision was disclosed in a widely read New York Times op-ed article. The actress, who was 38 and healthy at the time, had recently lost her mother to breast cancer. She had also been told that she was a carrier of the BRCA1 gene—a genetic mutation associated with high risk for breast and ovarian cancer.

In the 15 days following publication of the editorial, the British Medical Journal later documented, there was a sharp spike in BRCA tests in the U.K. alone, costing an estimated $13.5 million. BRCA testing remained at an all-time high throughout 2013. Strangely, mastectomy rates started plummeting 60 days after the editorial, falling from a stable 10 percent of all tested women to a low of 7 percent.

Angelina Jolie's op-ed did not cause a decrease in preventive mastectomies so much as an exponential surge in breast cancer screening among low-risk women for whom prophylactic surgery was unwarranted—women who would have been unlikely to get tested were it not for the actress's story. The sharp shift in public attitudes about genetic testing following the endorsement became known as the Angelina Jolie effect.

In an age of abundant medical data, ideas about breast cancer, faulty genes, and screening opportunities must have already been out there. Why, then, did so many women attend to the ideas only after Jolie showcased them, but not before?

This unusual imitation spree demonstrates the powerful effect that social influences can have on the body. And it offers some clues to the immense power of culture and how to mobilize it to exploit untapped resources in the mind. When the components are combined the right way, they can induce mental shortcuts that bypass analytical thinking and gain direct access to the array of physical functions regulated by the autonomic nervous system—digestion, heart rate, and blood pressure among them—processes not normally under conscious control. The result can be human healing responses of near-miraculous proportions.

The Power of Ideas and Prestige

In the age of secular humanism, ideas about souls and spirits that once held sway have lost their hold. The world's priestly classes—the theologians and mystics we trust to do the hard thinking about souls and spirits—have receded to the back stages of weddings and weekend rituals. A new canonical class of doctors and biologists—with knowledge of the invisible particles that regulate our health and life outcomes—evangelizes new truths about inner worlds.

But the recipe for influential ideas hasn't changed. For ideas to be powerful—particularly those esoteric ideas assumed to hold the mysteries of our existence—they must be wrapped in the power of a caste of experts who have undergone long initiation rites that justify their superior knowledge.

Sometimes, however, even the sermons of a priestly caste are not enough to convince the masses: Bombarding people with science-based, empirical facts about what is good or bad for them seldom inspires behavior change. But when prestigious people from our own cultural groups adopt a new idea, trend, or practice, we may choose to emulate them. Herein lies the power of celebrities: They are a demigod-like class of people imbued with enough prestige to be looked up to while still being credible as mortals we can relate to.

Harvard anthropologist Joe Henrich calls celebrity actions credibility-enhancing displays, acts that promote cultural learning by influencing cognitive processes. For a behavior to be imitated, it needs to be displayed by prestigious agents, people we can look up to as reliable sources of information.

There is, however, a delicate balance between "priestly" and "mortal" forms of prestige. When Angelina Jolie is caught in a genuine moment of heartfelt confession about her own mortality, people are especially likely to follow suit—believing they have chosen to emulate a prestigious agent.

Mental Shortcuts

A bias for prestige is built into the brain. It draws on remarkably efficient evolved mechanisms that enable our minds to zero in on high-quality information. In a world of exceeding informational complexity, the brain needs to focus on what is of immediate relevance and utility to our survival. The problem is, the human brain might be a little too efficient at simplifying things.

In seeking guides for our thoughts and actions, our prestige-hungry, information-simplifying minds crave people we associate with (the in-group bias) and zero in on specific in-group members with prestige and status (the prestige bias). We outsource to an in-group the task of gathering most of the information that is relevant to us, drawing on other cognitive biases about whom to learn from. This package of cognitive biases and social cues possesses the power to direct our attention, prescribe our beliefs and preferences, and guide most of what we do and think. It includes the fundamental attribution error: We focus on the attributes and personality traits of a single person when making sense of behavior while ignoring all the contextual, big-picture clues. The tendency runs deep in human psychology.

The package of cognitive biases also includes intuitive errors, which we make by way of the availability heuristic. Ideas that spring to mind effortlessly tend to reflect whatever we picked up from prior learning and frequent exposure—but not from critical thinking.

Here's a simple trick to try at home. Assuming they were raised in the West, ask anyone over the age of 10 the following question: "How many of each kind of animal did Moses take on the ark?"

Most people answer two. The answer, of course, is none. In the biblical story, it was Noah, not Moses, who brought the animals on the ark. The Moses illusion task is a famous measure of analytical thinking. Most people—including students and graduates of elite universities—fail to see the obvious answer.

The availability heuristic and intuitive errors tend to be primed by culture—that is, by ideas that seem intuitive because they are already culturally widespread, at least within one's specific group. In the Moses illusion task, most people raised in the West are so familiar with biblical stories that they invest no mental effort in examining the context of the riddle.

The words Moses and Noah share a phonetic structure, but more important, they are stored in memory within a similar cultural schema—a package of related thoughts and actions. People raised in countries in which biblical stories are distant and exotic tend to do much better on the Moses task. If they have to think "Wait a minute... what was that Ark-thingy again?" and remember Noah only with effort, the answer will seem obvious to them.

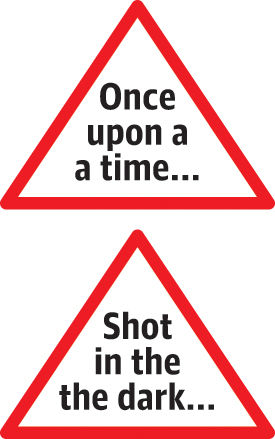

Can you remember the words that appeared in the red triangles a few paragraphs above? If you think they say "Once upon a time," and "A shot in the dark," think again! Try covering the words with a finger and reading them one by one. If, like most of us, you experienced difficulty in seeing the actual words in the triangle, you were trumped by a maladaptive schema.

The brain is a prediction machine. Prior learning prompts us to see the world as we expect it to be, not as it really is. Once a cultural schema is in place and the cues around us look right enough, we are blind to details and context; we automatically process information as we expect it to appear, without investing any mental effort.

From Biases to Body Control

In the popular imagination, placebos are pills that have no medicinal properties and work through the power of belief alone. Because people expect them to be medicine, and the priestly class of medicine is wrapped in a halo of prestige, expectations do the heavy lifting of healing.

But placebos need not entail a pill. Sham surgeries with nothing more than an anesthesia procedure and a superficial cut-and-stitch ritual have been shown to be very effective in the treatment of chronic pain.

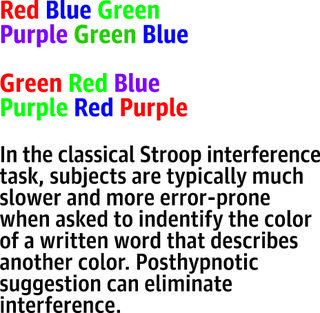

The Raz Lab at McGill University, where I work, specializes in the experimental study of the neural, cognitive, and social mechanisms that regulate attention and the powers of mind over body. Meditation, hypnosis, and placebo effects are among the many varieties of mind-body regulation that are of high interest to us. Before earning his Ph.D. in brain sciences, lab director Amir Raz spent years fooling audiences as a stage magician. A skilled hypnotist, Raz demonstrated that the famous Stroop effect, in which colors are confused with the words describing them, can be bypassed with hypnotic induction. He later found that when the context is right, a suggestion alone, without hypnotic induction, is sufficient to override Stroop interference.

Hypnosis, an atypical form of attention, is a remarkable phenomenon. When people relax their rational minds and loosen their vigilance mechanisms, they can be led to experience an array of extraordinary effects, from amnesia and burning sensations accompanied by boils and scars to rapid skin healing and the elimination of pain. But hypnosis procedures are demanding, and it takes time to learn to relax and let the unconscious mind take over.

Like hypnosis, schemas present another situation in which people bypass analytical reasoning. With schemas we process information in line with expectations. As we discovered in our lab, something similar occurs when we present subjects with cultural props that induce strong expectations of medical healing.

Most recipes for placebo effects draw on the cognitive biases of prestige and rarity and the power of priestly knowledge. Placebo effects are stronger when the experimenters look like real doctors and the settings appear clinical. Treatments that seem expensive and hard to obtain work better than those that look cheap and easily accessible. Technologically elaborate placebos (such as sham surgeries) work better than pills. When patients feel they have earned the experience, sacrificed something for it, and honed their anticipation in long waiting-room sessions, sham treatments work even better. Others draw on environmental cues: Blue and purple pills typically produce soothing effects, while red pills work best as stimulants.

Culture has a hand in here, too. For example, for Italian men, blue pills are not very successful at inducing calming effects. Why? Because Italian men tend to associate the color blue with their national soccer team and the excitement they feel during the games. For intuitions to be really strong, people must believe that many others in their group also expect the same thing. As our lab has discovered, tapping into deeply held cultural expectations begets the strongest healing responses of all.

In 2008, Harvard psychologist Irving Kirsch ignited controversy by pointing out that while SSRI medications used for treatment of depression outperformed placebos in clinical trials by only a very small margin, both drugs and placebos appeared to have become more effective over time. The scientific community was mystified.

When a group of psychiatrists from Columbia University reviewed 75 published trials of various antidepressants (tricyclics and SSRIs) compared with placebos, they found that, between 1981 and 2000, the effectiveness of drug treatment for depression trended up—from about 40 percent to about 55 percent—while the proportion of patients responding to placebos increased from 20 percent to 35 percent. The team concluded that unknown factors associated with the level of placebo response had changed.

For University of Michigan medical anthropologist Daniel Moerman, there was no mystery about the missing factor. In his view, the collective response is grounded in collective belief—a notable "shift in consciousness among doctors, patients, friends, and generally everyone, to the effect that depression can be treated with drugs."

As Kirsch sees it, the increase in efficacy was caused by two shifts in cultural expectations: an increased collective belief in the existence of depression as a brain disease and the belief that many who suffer from depression and take SSRIs have gotten better.

Over the past 12 years, drug companies in the United States have faced greater difficulty in completing clinical trials of new agents. It's not that the drugs have changed much but that there's a nagging interference in tests of their efficacy: The effects of placebos have gotten much stronger in several classes of drugs. An analysis of clinical trials of a pain medication conducted between 1996 and 2013, for example, found that the gap in effectiveness between medication and placebo dropped from 27 percent to a paltry 9 percent. The findings have proved robust in Canada and the U.S. but not in Europe or Asia.

The jury is still out on the causes of this effect. It may be related to direct advertising from pharmaceutical companies, which is legal only in the U.S. and New Zealand. But it showcases the faith placed in medical and pharmacological solutions.

Medical Magic

Explanations and technologies that involve neuroscience possess a similar power. In a series of clever experiments on what they term "neuroenchantment," Raz and his colleagues have found that even advanced students in psychology and neuroscience could be tricked into thinking that a sham brain scanner could produce improbable diagnostic and physiological effects.

Exposed to fake brain technology crudely built from a hairdresser's chair and discarded odds and ends, participants had no trouble believing that the machine was reading their thoughts. With a later, more realistic-looking (but equally fake) brain scanner, participants were convinced that the technology could not only read but also influence their thoughts; many reported an "unknown force" directing their thinking toward specific numbers.

Jay Olson, an experimental psychologist who, like Raz, first trained as a magician, finds that the sham scanner can even get participants to change deep-seated moral attitudes. The conclusion is clear: As decades of research in decision science have shown, humans are usually blind to context, prone to intuitive errors, and extraordinarily susceptible to culture and prestige. On the other hand, the same research reveals those processes as key to mind-body regulation.

Experiments conducted in our lab clearly show that when people's cultural schemas are carefully curated and met, hard-thinking cognitive resources shut down. And that opens the way to physiological responses that normally lie outside of conscious control.

Slow and inefficient, our reflective mechanisms are recent evolutionary developments that make huge demands on our energy. Hypnotists, magicians, and con artists are highly skilled at exploiting this design flaw to elicit confusion. Getting subjects to perform a simple mathematical operation or spatial reasoning task almost invariably makes them so blind to everything else around them that their watch or wallet can be lifted with little fuss.

The rational, volitional, thinking mind, truth be told, doesn't account for much in the realm of healing. From digestion and immune responses to heart rate, blood pressure, and pain, most of our physiological functions are regulated by the autonomic nervous system and are typically inaccessible to conscious control, although strong emotions like fear can radically disrupt any of them.

Real Effects

Olson and I have found that the symbolic power of mock brain technology and clinical settings can be very effective in the treatment of headaches, stress, anxiety, and involuntary behaviors like nervous tics.

Matthew is a 9-year-old who suffered from chronic debilitating migraines. Six months before our initial experiment, he was primed by being told that he "might have a chance to be selected for a very expensive new cure" in which an elaborate machine would "teach his brain how to heal itself and push out the pain of his headaches." Family members and friends told the boy stories of this revolutionary new treatment, and he began asking if he would be selected for the project.

When the day finally came, everything—the hospital setting, the waiting room, the large banners depicting cartoon brains and the word NEURO in light blue—conspired to induce healing expectations. Clad in white coats and wielding clipboards, Olson and an assistant walked Matthew through a perfunctory medical interview, then invited him to lie in the mock scanner. As he anxiously entered the noisy machine, he was told that "invisible gamma rays" would find the faulty connections in his brain and teach it to heal itself quickly.

Matthew later confessed to his father that he had had a migraine before entering "Dr. Olson's room," and that the pain disappeared minutes after he was put into the machine. Over the next few weeks, the frequency, longevity, and intensity of Matthew's migraines decreased by more than half.

In a second session, in which he felt more relaxed and eager to re-enter the machine, Matthew was shown sham 3-D brain images rotating on a computer screen. The first picture, representing his brain before treatment, was littered with red parts ostensibly showing where his pain originated. A second image, with radiating 3-D blue streaks, highlighted just "how well his brain had learned to heal itself." Four weeks after his second session, Matthew had experienced no more migraines.

Our pilot experiments strongly suggest so far that the battery of healing effects that can be induced under hypnosis can be replicated with greater ease under suggestion assisted with such accessories as white coats and noisy contraptions. The suggestive power of symbols, rituals, accessories, and curated contexts allows us to produce faster, stronger, longer healing responses.

Promoting accessory-assisted suggestion as evidence-based treatment might be a difficult sell. In theory, culturally widespread knowledge that the method is a placebo might dampen the effect. But our preliminary results suggest otherwise. When a few sessions in a sham scanner give clients the hope, then the expectation, then the proof that their symptoms can ameliorate or vanish, they subsequently come to expect that their brain has learned to fix a problem.

Once their attention is retrained and new skills are ingrained, the hindsight knowledge that treatment was initiated by suggestion is unlikely to reverse the new habits. In a very real sense, new automatic schemas are in place, and the clients' brains are rewired.

How Ethical Is It?

People may object to the use of suggestion on moral grounds. Suggestion raises difficult ethical questions and dilemmas on the nature and limits of truth and rationality.

On the one hand, cognitive science has shown that cultivating an analytical stance is critical in reducing intuitive errors and addressing our implicit biases. On the other hand, meditation, hypnosis, and placebo science have shown that tapping into our unconscious resources can have huge healing effects.

Suggestion-assisted healing cannot, and should not, be used for well-understood conditions that demand medical attention and respond well to pharmacological treatment. Culturally attuned, accessory-assisted suggestion cannot mend broken bones, prevent malaria, or substitute for insulin, chemotherapy, or physiotherapy. But it can help people who suffer from syndromes and chronic conditions that elude current medical understanding and treatment.

The healing potential of culturally enhanced suggestion may become the new no-brainer treatment choice for many conditions that resist standard medical care.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue