Tend and Defend

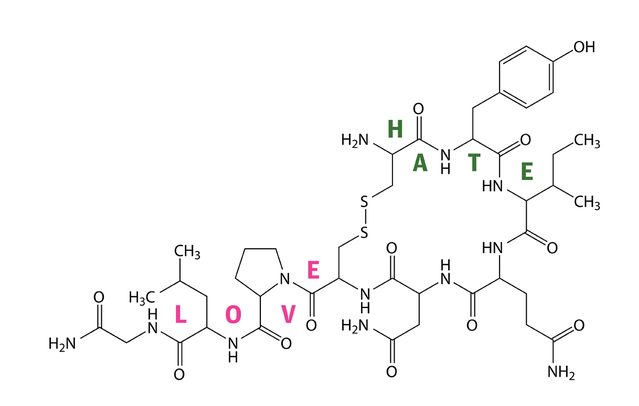

Oxytocin is best known for generating human connection, but research increasingly reveals that the hormone has a dark side.

By Jennifer Bleyer and Christopher Badcock Ph.D. published March 7, 2017 - last reviewed on May 1, 2017

Hormones are often cast in an exclusively positive or negative light. Testosterone, for example, is the archetypal rogue hormone blamed for all manner of bad behavior. Oxytocin plays its virtuous opposite, thought to leave nothing but warm, fuzzy feelings in its wake.

But hormones aren't substances that monolithically determine how people feel or act. Rather, they're chemical messengers that rely on receptors in the body and brain to trigger their effects—effects that are much more complicated than "good" or "bad." And in the case of oxytocin, researchers are increasingly identifying a dark side of the so-called "love hormone" that counters its cuddly image.

Released by the brain's hypothalamus, oxytocin plays a role in a wide range of prosocial behaviors. It facilitates social bonding and acts as a buffer against stress, anxiety, and depression. It cements attachment between mothers and babies, bathes the brains of couples falling in love, and floods the body during orgasm, strengthening intimate connections. One might think of oxytocin as the magic ingredient in Danish hygge—the cozy, contented feeling of being with trusted others.

Yet the same hormone that helps people feel warmth and camaraderie with friends and family is also implicated in the hatred and contempt they may feel for opponents. In recent years, researchers exploring the intricacies of oxytocin have revealed that it rouses envy as well as gloating over others' misfortune. Psychologists conjecture that oxytocin plays a part in fueling ethnocentrism, xenophobia, and intergroup conflict.

In 2010, social psychologist Carsten K. W. De Dreu reported the results of a series of double-blind, placebo-controlled experiments in which he'd set out see whether the oxytocin-fueled trust in one's own group has a related outcome of promoting distrust of other groups. The experiments, published in the journal Science, grouped men randomly and then asked each to participate in a game with financial consequences for himself, his own group, and competing outgroups. Compared to those who received placebos, De Dreu found that those who were administered oxytocin were more favorable toward their group—and less cooperative toward the outgroups.

In a paper published the next year, De Dreu extended his study to ethnocentrism by testing the attitudes of indigenous Dutch men toward Arabs and Germans. One of the experiments in the follow-up study posed a classic moral dilemma, telling the Dutch men that a trolley was careening toward five nameless people who would be killed if nothing was done. The participant had an option to hit a switch and divert the trolley to another track where just one person would be killed. In De Dreu's dilemma, the potential victim had either a Dutch or Arab name. Participants who were adminstered oxytocin were much more likely to save a prospective victim named "Maarten" and to sacrifice a prospective "Muhammed." There was limited support for the idea that oxytocin actually enhances the willingness to sacrifice the out-group, but De Dreu theorized that "through its influence on in-group favoritism, oxytocin contributes to the development of intergroup bias and preferential treatment of in-group over out-group members."

Drawing in part on De Dreu's work, Amar Annus, an associate professor of Middle Eastern religious history at the University of Tartu in Estonia, put forth a theory that ancient Mesopotamian people reflected hormonally powered beliefs in their religious doctrine. In texts from the first millennium BC, the Assyrian king is portrayed as a baby—suckled, comforted, and protected by the goddess Ishtar—who appears as his mother or wet nurse, and is also shown fiercely attacking the king's enemies. While Ishtar's role as the goddess of both love and war may seem paradoxical, Annus says it suggests that ancient people observed what science has only recently begun to parse.

"When you look at ancient Mesopotamian religions, one becomes aware of so many paradoxes," Annus said. "It always seemed a contradiction to me that Ishtar was a goddess of both love and war, but when I found out about this study of hormones, it became clear why people saw her this way."

Previous studies have linked oxytocin to religious feeling—prayer, for instance, releases oxytocin and activates the same neural pathways as social interaction, and oxytocin has been shown to enhance spirituality. To the extent that oxytocin is involved in religion, and to the extent that religion has historically fueled violence and persecution, the hormone may help explain both the good and bad behaviors provoked by spiritual belief.

Annus, who is working on a book about traces of biology in ancient religions, argues that because religious and nationalist feelings emerge as natural byproducts of the prosocially wired brain, a society without religion or nationalism is impossible, and it's the role of society to be aware of the connection and mitigate its negative effects through humanistic principles and well-informed science.

For the "love hormone," a moral of the story seems to be that one should neither blame—nor lionize—any chemical messenger. While oxytocin may indeed inspire love, it may also drive hate and hurt. By allowing for a more nuanced understanding of all hormones, we may learn not only how to encourage their benefits, but also how to lessen their more destructive consequences.