Odd Emotions

By coming to grips with unnamed feelings—from the need to connect deeply with someone we've just met to the desire to know how things will turn out—we can master our interior life.

By Rebecca Webber published January 5, 2016 - last reviewed on June 10, 2016

The feeling first came over Carrie Aulenbacher after her grandmother died in 2008. "I was old enough then to have an introspective moment about my own death," says Aulenbacher, 37, of Erie, Pennsylvania. "I thought about no longer having a body and no longer feeling. Not being here at all." Trying to imagine her own nonexistence caused cold, heart-pounding fear: "It was an emotion I could not label."

Occasionally, that eerie feeling comes back, spooking her, even making her cry. "I recently got upset about a work situation," she says. A coworker had misunderstood her instructions and botched a project. "I was really frustrated, so I tried to calm down on the drive home," she says. Seeing the blue sky with clouds stretching out before her, it occurred to her that her stress was infinitesimally small in the context of all the time that had passed before she was born, and all that would go on long after her death. She dabbed away tears as she wondered "what eternity would be like. Not being here to love my son, and make coffee, and deal with any work projects at all."

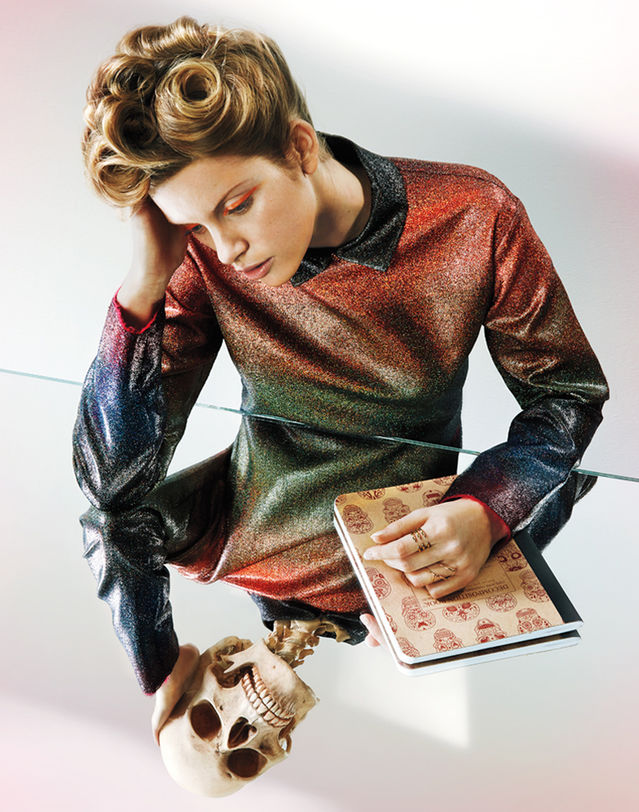

The Latin phrase memento mori means "remember (that you have) to die." It's a concept that appears in Plato's recounting of the death of Socrates and later found a foothold in Christianity. But there is no simple word for it in English.

Or there wasn't, until artist and writer John Koenig, 32, decided he needed to create one. "For years I would get these sudden, stabbing chills when falling asleep, as I remembered that I was going to die one day: This is not a game or rehearsal. This is it. Life is slipping away second by second," he says. After some linguistic research, he christened the feeling moriturism. "Once I gave a name to it, it felt somehow OK," he explains. "Recognizable. Less an abyss than a well-marked pothole. Now it doesn't bother me as much, because I feel like I can control it."

Unusual emotions routinely swirl within us, and they aren't easily named. But it may be useful to stop, examine them, and try to put them into words. "When we label an emotion, it might make it more manageable," says Seth J. Gillihan, a clinical assistant professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. "It might not change the emotion, but it does allow us the possibility of choosing our response."

Our Deep, Confounding Feelings

You would assume that there's an agreed-upon definition of emotion, at least among those who study and write about it professionally. You'd be wrong. "There are several different definitions, each aligned with a particular theoretical view," says Lisa Feldman Barrett, a psychology professor at Northeastern University and the author of the forthcoming book How Emotions Are Made. "I think that an emotion is your brain categorizing sensations, making them meaningful so you know what they are and what you should do about them."

Attempts to pinpoint emotion centers within the brain have been largely unsuccessful. "Empirically, there's no biological imprint or even neural circuit for a category of emotion like 'anger,'" Barrett says. Instead, our inner feelings appear to arise from complex systems of chemical and electrical interactions within and between cells.

Labeling emotions isn't necessary for their primary—and immediate—purpose. "The conscious understanding of emotions is superfluous from a survival standpoint," Gillihan says. "If I'm running away from a tiger in caveman days, I never say to myself, 'I am afraid.' I just think, Tiger! I've got to get out of here! I handle the threat and survive." In modern times, however, our feelings often arise from our relationships, careers, and travel, and we benefit from a more considered response, he says. "It helps to be able to put a frame around more complex emotions."

Aristotle categorized many familiar emotions—anger, fear, shame, pity, love. But our feelings often seem far more nuanced than these common terms can capture. At a given moment, they might incorporate varying shades of multiple emotions or be heavily influenced by context. Consider pride: We feel it when we've accomplished something difficult or impressive at work. But that's different from the pride we feel when our adult child achieves a milestone. Or the pride that surges through us when our national soccer team wins the World Cup. The variation in just one significant variable—cause—changes our experience of pride and our resulting actions: We might bask quietly in success at work, brag to friends about our child, or high-five strangers in soccer jerseys on the street.

"I think about our descriptions of emotions like our descriptions of the weather," says Mark R. Leary, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. "There are all different kinds of cloudy days. There are really dark, cloudy days; there are bright, cloudy days; and then there are cloudy days where the sun just breaks through. Sometimes it's raining and sometimes it's not. But we use a single word to describe it: 'It was cloudy today.'

"Emotions don't come in neat little boxes," he says. "They're often blends of a lot of different things you're experiencing." For example, we can feel happiness tinged with sadness, and happiness accompanied by fear. "I'm happy to get this job, but I'm also afraid because I'm going to have to prove myself," Leary says. "You have these mixed feelings that don't feel exactly like any of the standard emotion words because they're a mixture of things. A lot of dimensions are being activated."

And while emotions sometimes do combine smoothly into an easily comprehensible new experience, the way a tiny dab of white paint can turn a dollop of red paint a vibrant pink, at other times they clash and confuse, leaving us unsure how to respond.

Dale Koppel, 72, of Boston recounts a recent vacation in Italy with her husband and four other couples, including a man—let's call him Hank—whom she had never much liked: "He thinks nothing of making racist and homophobic comments." On the trip, Hank almost immediately made a vile remark that felt personally insulting to Koppel, while another man in their party stood by silently. "It wasn't just what I felt about what he said. It was about the other man not even speaking out," she says. Koppel was insulted, angered, saddened, and hurt, all at the same time: "Sometimes it's the depth of an emotion that cannot be described, especially when you're around people who seem unable to identify with it."

Koppel tried to challenge Hank, but got nowhere. And while the other members of the group supported her when she talked to them about it, no one mediated the issue. "It was extremely awkward," she says. "I held my tongue to keep the peace, and the situation wasn't resolved." Weeks later, it still rankled her. Koppel's experience happens to correspond with what Koenig has named exulansis—a sense of frustration when you realize that you are trying to talk about an important experience, but other people are unable to understand or relate to it, so you give up.

"Emotions have motivational consequences," Leary says. "They tell us what to do." Fear tells you to get away from danger. Anger tells you to strike out or defend yourself. "If you can't tell what you're feeling, then it's a lot more puzzling to know how you should react: I don't know whether to laugh or cry. I don't know whether to approach you or avoid you."

Emotions that Evade Labels

Our ineffable feelings come from all manner of inputs, from external circumstance to internal musings. Many, though, tend to fall into some broad categories of experience.

Encounters With Nature

As we spend more of our time staring at screens, many of us spend less of it stargazing or walking in the woods. But throughout human history, our encounters with the natural world, whether looking at calving glaciers, leaping schools of dolphins, or soaring sequoia trees, have inspired novel feelings.

"At night, if you look out at the big, rough ocean, you probably feel scared because it could engulf and kill you," says Eric Wilson, an English professor at Wake Forest University. "But you might also feel elevated. You feel reduced to an insignificant speck in a vast universe, but also feel as if you're as big as that universe."

Both in spite of and in pursuit of these confounding feelings, everyone from poets to joggers seeks time alone in nature. "Everything's quiet but the birds, and there's this really relaxing calm," Leary says. "It's more than normal calmness: There's a sense of connection to the woods and other things wrapped up in there, feelings we don't have really precise words for."

Clinicians routinely encourage people to spend more time in nature as a way to create the mental space we need to better understand our emotional state, even as we're creating new ones. "When we have time to reflect and be alone, to daydream, take a walk, and have spontaneous thought—this is how we know ourselves," says Carrie Barron, an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University. "This is how we understand what affects us, what we feel deeply about, what moves us, and what doesn't really move us. I think it's very important for our mental health to have that thread to our deeper self."

Even interactions with depictions of nature can push our emotions to extremes. "Powerful art, be it painting or music or poetry, de-familiarizes our sense of the world," Wilson says. Stare at Van Gogh's The Starry Night, and you can get lost in the colors, the brush strokes, and the vibrancy. Afterward, your own vision of the nighttime sky may look different. "It's the same sky, but it's a little strange now," he says. "Art can weird the world, if you will, but in a way that's enlivening to us."

Encounters With Time

We typically measure time by the ticking of a clock—knowing the rough duration of a second, an hour, a day—but certain experiences challenge that understanding. Life experience tells us that the old adage, "Time flies when you're having fun," is true, but we feel a similar effect at our office on Monday morning, when it's lunchtime before we even feel settled, and perhaps the opposite effect, time dragging, as we await 5:00 on Friday.

Other experiences, rooted in fear, can also make us feel as if the seconds have slowed to an unbearable crawl—such as when you're in the dentist's chair. At moments of peak stress, an increase in the stress hormone cortisol intensifies our encoding of memories of scary experiences. Studies have shown that people who are afraid of spiders, for example, overestimated how long they had to look at them, while new skydivers thought their falls lasted longer than they did.

Lisa Finkelstein, 50, of Tallahassee, Florida, remembers a moment when time slowed down for her: Carrying too many books as she exited a library, she tripped and tumbled down the concrete stairs. The fall could have taken only a few seconds, but to her, it felt far longer. She remembers her toes grazing the edges of the steps, the open-mouthed look of surprise on the face of a child in the parking lot, and the soft thud as she crumpled at the bottom—fortunately, mostly unhurt.

For Cynthia Larson, 54, of Berkeley, California, time occasionally gets ahead of itself. Once, while expecting her daughter's arrival home, Larson could have sworn she heard her, even though her daughter wasn't yet there. Norwegian actually has a word for this—vardogr—meaning a premonitory sound or sight of a person before he or she arrives. So does Finnish. But not English.

Encounters With Other People

Our social lives regularly inspire emotions from the loving to the murderous. Many have no English name, but you're probably familiar with the German term schadenfreude, which describes the pleasure we may derive from someone else's pain. The word made rare appearances in English publications before 1985, according to Google's ngram tool, after which usage of the term shot up tenfold.

But even a term which so many of us have added to our repertoire of experiences can come up short. Joanne Cleaver, 57, of Manistee, Michigan, for example, has felt a "deflated" variation of schadenfreude, which she describes as when someone "finally comes around to your point of view or is served a very cold helping of karma, but sadly, you've matured past the point of really caring anymore." It happened to her when an old frenemy who had disdained her in the past for being a working mom responded to Cleaver's Facebook post about a career achievement by writing, "I always envied you, even when our kids were little."

The frenemy was probably experiencing an ineffable emotion herself, Gillihan says, "the sort of envy that you feel seeing someone's carefully produced life on her Facebook page. It's helpful to tell yourself: 'OK, that's a thing. People feel crappy when they see other people's fabulous posts on Facebook.' It normalizes the emotion."

Social media in general have given rise to a wave of new, nameless feelings, many based on how disconnected we often feel even while being only a text or tweet away from just about everyone we've ever met. "We are animals, and connection is really important," Barron says. "The subtleties of facial expression, body language—even on Skype, you don't see them and feel them in the same way." She suspects that disconnection is a key factor in the widely reported increase in depression and anxiety among American college students.

And yet overwhelming feelings of connection have their own uncanny power. Finkelstein remembers one random drive home from the grocery store when she was overcome by an encompassing love and acceptance of everyone she saw: A couple standing outside a pay phone struggling with the classified ads. A large woman with an unusual hairdo walking on the side of the road. A middle-aged man with a gun rack in his truck window. "None of these people were the types I hang out with, but I felt a great and equal love for all," she says.

Encounters With Ourselves

When we're faced with choices that can change the course of our lives, we inevitably have to confront feelings we can't quite pin down, although if we could, it might make our decisions clearer. "When we use cognitive behavioral therapy, we usually focus on valued actions, choosing things that are consistent with our values, rather than making spur-of-the-moment decisions," Gillihan says. "Then we end up living lives that are in line with things we actually care about."

Charlie Houpert, a 28-year-old Philadelphian living in Medellin, Colombia, has felt the strange comfort that comes from resigning himself to a painful or difficult action because he knows it's the right thing to do, like confessing a mistake to someone he's hurt or volunteering to sing karaoke, which scares him. The feeling is "a mix of trepidation, because you know it will hurt, but also clarity, because you know you are taking the right path," he says. "You feel yourself resist the action, but you also feel at peace with yourself."

Leah Jones, 38, lives with an ongoing conflict about where she should reside, an emotion she describes as a sort of reverse-homesickness. She yearns to be in Israel, which she has visited nearly a dozen times since converting to Judaism. But family responsibilities, immigration complexities, and professional obligations keep her in Chicago. What she feels is "more than longing, but it's not nostalgia," she says. "It's more like the homesickness of study abroad, but in reverse." Students abroad wish they were home. Jones is home, but wishes she were somewhere else.

Mastering the Feelings You Can't Pin Down

Psychoanalysis, Barron explains, distinguishes the experiencing ego from the observing ego: The former, she says, "experiences, feels, and is thrown by the emotion. The latter can step outside of the emotion and say, 'OK, I was thrown, I am upset. I feel despair. Here, I can look at it and I can name it, and that is a step towards managing it.'"

Our states of inner feeling are a great source of information, and those that are hard to name have a special sort of power: "They are so intense, so overwhelming, that we lose our ability to step outside of them, put a circle around them, and call them something," she says. If odd emotions disturb or distract you, a therapist could help you sort things out and, if possible, put them into words. "It might be fear for you. It might be anger. It might be tenderness," Barron says. But it's almost never just one thing: "Conflict and ambivalence are part of the human condition. You might feel two opposite things at the same time. But when you can name it, you are more in control. You feel better."

Once you have wrapped your head around, or even named, an odd emotion, you can do something with it, and about it. You might make a change in your life, so that you don't experience an unpleasant feeling as often—or so you're more likely to feel a lovely, hard-to-capture one. With work, you can ideally become able to simply sit quietly with it. A crucial realization, Barron says, is that "running from emotions is much more exhausting than actually feeling them."

You can apply the skills of emotional interpretation in your daily life, Gillihan says, where some of us are prone to bouncing off emotions in unconsidered directions. An extreme example: You're driving on the highway, you get cut off, and you see red. Your knee-jerk reaction is to retaliate and punish the aggressor. You might flash your brights or tailgate. But at the same time, "there may be a tiny voice in the back of your mind saying, 'You probably shouldn't be doing this,'" he says. "If you can take a moment to recognize: This is how I feel. Now how do I want to react to that?" then you might end up making a better decision. And if you can call on that voice again in a moment of stress, by name or not, you may avoid a life-changing mistake.

A Glossary of the Uncanny

Many languages have words for emotions for which there is no direct English translation, schadenfreude being perhaps the best-known example. "It wasn't that people never felt pleasure at another's misfortune before," Barrett says, "but without a word, there were no normative rules for it. If I told my lab about a colleague who had treated me very badly once and, later, he didn't win some important award, and I said I felt pleasure in his misfortune, they would think, 'What a horrible person!' But now that we have the word, I can say I felt a touch of schadenfreude, and they will understand. Once a concept has a name, all of a sudden there are cultural rules for when it's OK to feel it. So now it's OK to have schadenfreude at certain times. People will think of you as more human and be more likely to join you in that feeling for a brief moment."

Jesse Till, 25, a native of Honduras living in Orlando, Florida, sometimes feels pena ajena, directly translated as "foreign embarrassment." "It's feeling embarrassed for someone, but not in an empathetic way. It's more of an 'it's painful to watch' kind of way, when you have to turn away or change the channel," she explains.

"In English, anger is one concept," Barrett says. "In German, there are three. And in Mandarin there are five concepts of anger. What differs among cultures is what you're calling out as a significant shared experience."

Examples of potentially useful expressions abound: The Dutch talk about feeling gezellig—that warm, delighted sense you get when spending time with dear friends. Russians have razliubit—the emotion of falling out of love. And the Japanese have age-otori—the regret one feels after getting a bad haircut. ("I need that concept, for sure," Barrett says.)

But no language fully satisfies or could ever keep up with the complete array of human emotion. It may be a task beyond our capabilities, like naming every possible gradation of color (although marketers have made noble efforts).

"People like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth had a real sense that there are certain experiences that language cannot describe," Wilson says. "For them, those are the most important experiences." These Romantic poets referred to such feelings with the bucket term "the sublime," which, Wilson says, included "any experience that was overwhelming, that made us feel pain as well as pleasure, that struck us as boundless and infinite and weird and bizarre and outlandish. They believed that we're most alive when we're having these experiences that we can't quite name." And while the sublime could not be fully captured in words, literary language helped them grope toward an explanation.

John Koenig joined this effort 10 years ago, when, as a student at Macalaster College in Minnesota, sitting in the campus library trying to write poetry, he imagined a book—The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, "so old its pages shattered in your fingers when you turned them," he says. "It had full Latin classifications, different conjugations of sadness, little daguerreotypes of various woeful faces. Very mysterious in tone, somehow both clinical and heartfelt." The image stuck with him, he says, "this idea that all the built-in confusion and emptiness of being human had already been fully documented, that someone had waded into the psychological wilderness and mapped it all." But no one actually had. Three years later, he decided to give it a shot—with a Tumblr page.

On his site, Koenig strives to grasp the often-fleeting emotions that strike us in rare moments, examine them at length, "like moths pinned in a little box," and, finally, name them as elegantly as he can: The perverse pride we feel about a scar (scabulous), for example, or the sudden, shocking realization that every other person is the protagonist of his or her own life (sonder).

He often begins with a related word, then explores its etymology using virtual and printed resources, seeking ways to combine word roots. Avenoir, a mashup of the French words for "future" and "memory," is defined by Koenig as the desire to see your memories in advance; opia is the ambiguous intensity of looking someone in the eye, which can feel simultaneously invasive and vulnerable; and chrysalism is the amniotic tranquility of being indoors during a thunderstorm.

Koenig's goal, besides word creation for its own sake, is to reassure visitors to his site that, as he says, "Whatever you're feeling right now has been felt by someone else out there."

Trying to name our own odd emotions—or seeking out other cultures' terms—can be fun and enlightening, but there's a larger purpose. "It's good to have a sensitivity to your inner state, not that there is a right or a wrong, or that you have to always be labeling yourself," Barron says, "but to know how you are moving and shifting and what the dynamics are."

She recommends making a regular habit, whether for a few minutes a day or an hour a week, of "going without structure into your mind and being there. Know what's going on. Honor those powerful personal emotions. They are what make each of us unique."

The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

Writer-artist John Koenig attempts to capture the ineffable on his website by coining names for complex feelings. the Following are just a few of his original terms for previously unnamed emotions:

Adronitis: The frustration with how long it takes to get to know someone, and the wish that you could start by exchanging your deepest secrets.

Ellipsism: The sadness that you’ll never be able to know how history will unfold.

Enouement: The bittersweetness of finally seeing how some aspect of your life turned out, while wishing you could share the news with your younger self.

Occhiolism: The awareness of the smallness of your perspective, from which you couldn’t possibly draw any meaningful conclusions because your life has a sample size of only one.

Pâro: The feeling that no matter what you do, it’s always somehow wrong, that there’s some obvious way forward that everybody else can see but you.

Vemödalen: The frustration of photographing something amazing when thousands of identical photos of it already exist.

Zielschmerz: The exhilarating dread of finally pursuing a lifelong dream, which requires you to put your true abilities out there to be tested on the open savannah, no longer protected inside the terrarium of hopes and delusions that you created in kindergarten and kept sealed as long as you could.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.

Facebook image: racorn/Shutterstock