Two-Minute Memoir: My Muse (With Benefits)

Sometimes right and wrong can get all mixed up when the pleasure principle comes into play.

By Mark Matousek published May 3, 2011 - last reviewed on December 21, 2020

I didn't know my teacher was a thief until after she had already seduced me.

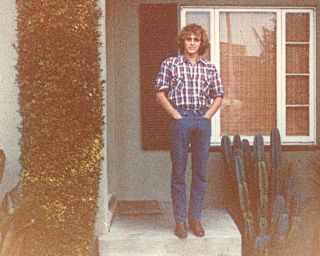

The night it happened was magical. I was a 19-year-old surfer from California enrolled in Marguerite's* college French class. She was a 33-year-old, Sorbonne-educated hottie with a mammoth intellect and luminous copper eyes. Our chemistry was heated and glaring. A few weeks into the semester, Marguerite invited me to dinner. After couscous and wine at her bachelorette pad, she led me by the hand into an Arabian Nights bedroom, complete with a hookah and shawl-hung lamps casting it in a scarlet glow, and had her illicit way with me. I felt as if I'd won the sexual Megamillions jackpot.

I wasn't a virgin—sexually speaking—but I was a suburban hick. Marguerite, I soon realized, was a different breed altogether: a Continental rebel with three holy causes (Plaisir! Liberté! Beauté!) peppered with revolutionary mischief. She was the first freethinking person I'd ever met, refusing to conduct her life minding "bourgeois rules made by idiots!" Marguerite saw nothing wrong in getting students drunk (before sleeping with them), cheating on her taxes, lying to authorities, and flouting every taboo imposed by the Power Elite. Civil disobedience was a badge of honor to her, a duty for nonconformists (like us!).

Her rebelliousness worked in my favor, of course. My mentor amoreuse craved forbidden fruit. Her pet pastime—aside from sex in movie theaters, automobiles, library bathrooms, and her office—was shoplifting erotic accouterments from big-name department stores. Marguerite's favorite contraband was expensive underwear from Macy's and Saks, panties and peignoirs, bras and G-strings, secreted in an attaché case. I was scandalized the first time she told me this but petty thievery was her idea of fun, and since Marguerite only ripped off corporations—never a Mom-and-Pop place where an individual's business would suffer—she justified her dishonesty using proletariat politics.

"Regardes!" Marguerite liked to taunt me after her retail excursions, parading half-naked around the apartment, her kittenish body barely draped in frilly booty with the tags still on.

"Tu l'aimes?" she would ask, twirling around to provide me with the full, lascivious view.

"Je l'aime beaucoup!" I would assure her.

"You must think I'm v-e-r-y bad," she'd tease her puritanical ward, metallic eyes shimmering with delight.

"Very," I'd say, half turned on, half judgmental. There was no use trying to discipline her. In seconds, we'd be at it again.

In truth I was ethically flummoxed. Before meeting my enfante terrible, I thought I understood right and wrong. Now my belief system had split and seemed to be operating on two tracks. On the first, old-fashioned morals held sway; truth and falsehood, crime and punishment, law and order were clear. On the second, things were messier, up for grabs. "When the penis gets hard, the brain goes soft," the Germans say, and in Marguerite's irresistible arms, I felt morally flaccid for the first time.

Our outlaw relationship was showing me who I was, and who I wasn't, when testosterone competed with conscience. Je m'en foutisme, the French call it, the practice of not giving a damn. As a teenager who took things way too seriously, I found it liberating to be with someone who cared so little about social convention. Though I didn't condone her dishonesty, I appreciated the whiff of freedom.

I also thrived on her encouragement. Marguerite was the first person to suggest that writing might be my vocation. At her insistence, I entered a statewide essay competition and won first prize. She introduced me to writers I'd never heard of: Camus, Baudelaire, Yourcenar. She became my muse with benefits that year and, after graduation, invited me to travel with her for a month in Europe. She showed me the building in Paris where Oscar Wilde had uttered his dying words. She sat with me at the table at Café de Flore where Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir argued over infidelities. After Paris, we drove south to Nice, where I found a job slinging barbecue for singer Josephine Baker's brother at the jazz festival. One night, James Baldwin—one of my literary heroes—stopped by for a visit and spent an hour in our tent, smoking cigarettes and giggling like a schoolgirl on the lap of his musclebound boyfriend. Marguerite was thrilled to be grooming me for a writer's life, to be watching me outgrow my suburban naivete and expand toward the land of outcasts and artists.

After Nice, we drove to Barcelona—where we rented a room in a brothel—then down to Marguerite's tiny farmhouse in Andalusia, a rustic aerie overlooking fields where bulls were fattened for the corrida. After indulging in ice cream under a chestnut tree one afternoon, we followed a road up a gorge to Pujera, a collection of whitewashed cottages blooming with bougainvillea and nestled on the mountainside. Marguerite was wearing a white peasant dress with magenta stitching and clear plastic sandals she'd stolen from Uniprix (in spite of my pleas to let me buy them). We sat on a bench and ate apricots from her garden, gazing down into the valley.

Marguerite remains to this day the sexiest, most troubling, most enlightening woman I've ever known; still, her wobbly conscience never ceased to bother me, like a crack in an otherwise water-safe vase. But in that moment, my conscience was quiet. Marguerite's head was leaning against my shoulder, a sultry breeze was warming us, and I felt more perfectly happy than I could remember feeling before. It will never get any better than this, a voice inside me said. And it hasn't.

*Name has been changed