Myers-Briggs

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is an assessment of personality based on questions about a person’s preferences in four domains: focusing outward or inward; attending to sensory information or adding interpretation; deciding by logic or by situation; and making judgments or remaining open to information. The MBTI was initially developed in the 1940s by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter, Isabell Briggs Myers, loosely based on a personality typology created by psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

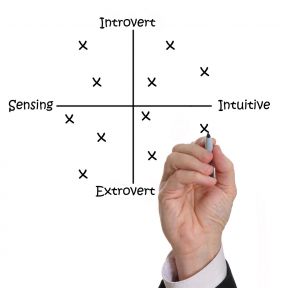

When responses are scored, the assessment yields a psychological “type” summarized in four letters, one for each preference: Extraversion (E) or Introversion (I); Sensing (S) or Intuiting (N); Thinking (T) or Feeling (F); and Judging (J) or Perceiving (P). The results combined into one of 16 possible type descriptions, such as ENTJ or ISFP.

While the MBTI is used by many organizations to select new personnel and has been taken millions of times, personality psychologists and other scientists report that it has relatively little scientific validity. Psychologists who investigate personality typically rely on scientifically developed assessments of traits clustered into five (the Big Five) or six (HEXACO) domains.

Why do experts take issue with the MBTI? One reason is that while the Myers-Briggs assigns people distinct types, scientific evidence indicates that personalities do not fit neatly into 16 boxes.

Traits are more accurately viewed not as categorical dichotomies—extrovert or introvert, thinker or feeler—but as continuous dimensions: For each trait, an individual can rate relatively high, low, or somewhere in the middle, and most people fall in the middle. Personality tests favored by scientists, such as the Big Five Inventory, describe each personality not in categorical terms, but rather based on how high or low a person scores on each of five (or six) non-overlapping traits.

The MBTI’s type-based feedback is also not especially consistent; a person who takes the test twice may well receive two different type designations. Moreover, the MBTI omits genuine aspects of personality that have negative connotations, such as neuroticism (emotional instability) or facets of low conscientiousness. It is untrue that the MBTI measures nothing at all, however. Research suggests that when MBTI preferences are evaluated as continuous dimensions, rather than split into categories, there is some correlation with scores on the Big Five traits.

The MBTI’s type for any one individual is often not consistent over time: People may take the test on multiple occasions and receive different personality types, even if they have not changed drastically in real life. Research has found that over a period of only a few weeks, up to half of participants received two different type scores.

Developers of the MBTI even acknowledged that in their sample, 35 percent received a different type after a four-week period. And despite the use of the MBTI in work settings, research does not suggest that the MBTI types are especially good predictors of job outcomes.

Forced choice fails to capture the dimensional nature of personality. The MBTI’s scoring format places individuals into one of each pair of categories regardless of how extreme their scores are. A person who scores a 53 percent on the introversion-extraversion dimension receives the same result as someone who scores 95 percent: Both are labelled “extravert.” The person who scores 53 percent, however, is probably much more similar to the “introvert” who scored just below the 50 percent mark.

Personality “types,” therefore, miss a lot of information; characterizing everyone as either an introvert or an extravert glosses over the reality that most people actually land somewhere in the middle of the spectrum.

The notion that personality is completely fixed from birth isn’t accurate, and it can be valuable to possess flexibility in how people view themselves and their ability to evolve. But when people take a personality test, they may adopt that label and incorporate it into their identity and life narrative. Labels can be limiting, which is why it’s important to acknowledge the limited nature of the Myers-Briggs itself.

The MBTI has been used in an array of domains. Companies have used it to hire and organize employees. Career advisors have used it to recommend which professions individuals should explore. Premarital counselors have used it to gauge the “compatibility” of couples. However, there is little evidence to support the connection between the Myers-Briggs and outcomes such as job performance or relationship success.

Despite its limits as a valid personality assessment, the Myers-Briggs can be a valuable tool for self-reflection. Taking a fun personality test can serve as a starting point for people to consider how they view their personality, how human behavior can vary, and how they relate to others in their life. The MBTI can provide an initial vocabulary from which to expand.

Personality tests have almost become ubiquitous. A high school guidance counselor may assign students to take a personality test to determine which colleges to apply to. Corporations may administer tests for hiring decisions or team-building activities. Personality tests may lead friends to bond over a shared “personality type,” find others like them, or put words to different dimensions of character.

The desire to understand ourselves better and categorize the world around us helps drive the popularity of the Myers-Briggs and others like it.

People are endlessly fascinated by personality tests. This may be because people seek hidden information about themselves, wanting to understand and access their true nature. People also have an inherent desire to belong; identifying with a “type” can help people feel normal and understood—there are similar people out there. People also appreciate simple ways to categorize and interact with other people.

The Myers-Briggs often delivers results that aren’t entirely reliable—so why do people trust them? One reason for this illusion of accuracy is confirmation bias: When people believe something is true, they begin to filter information based on that belief. People may also love the feeling of being recognized, like the test “gets” them. The results are fairly general which makes them widely applicable, and they skew positive so people are often happy to accept them.

The MBTI is perhaps the most well-known, but other popular personality tests include the Enneagram, which assigns personality descriptions based on nine primary types and often secondary types called “wings,” and the DISC, assessments that assign individuals one of four types, or a blend of the types: Dominance (D), Influence (I), Steadiness (S), and Conscientiousness (C).

Psychologists generally agree that tests of the Big Five personality traits are most valid. The current version of this assessment is the Big Five Inventory-2 (BFI-2).

Most personality psychologists use tests that measure the Big Five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. These five traits represent five categories of individual characteristics that tend to cluster together in people.

This framework has the benefit of 1) being developed with the scientific method 2) using continuums rather than categories 3) showing how people change over time 4) predicting outcomes that personality should predict, such as life satisfaction, education and academic performance, job performance and satisfaction, relationship satisfaction and divorce, physical health, how long people live, and more.