Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

8 Ways CBT Can Improve Your Relationship

Happier individuals have more to give their partners.

Posted March 6, 2017 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

So many of the people I treat in my practice come to therapy because their relationships are suffering, and so they are suffering. It could be a teenage boy whose severe social anxiety prevents him from spending time with friends, a woman with depression that makes it hard to be the partner she wants to be, a father whose expressions of anger have put distance between him and his kids, or a college student whose alcohol-fueled behavior has alienated her friends. It's hard for our relationships to thrive when we're hurting.

Effective therapy can improve our relationships, whether or not those relationships are the specific target of the treatment. A relatively brief course of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—which has been tested more than any other treatment—can lead to marked benefits not only for the person in therapy but for those close to him or her. Some of the major relationship benefits include:

1. Greater presence. It's hard to overstate the importance of our presence in a relationship, since we can't truly "relate" to someone who's not there. One of the biggest complaints about partners that I hear in my practice is that "s/he isn't there for me." Sometimes the person means quite literally that their partner is absent—always traveling for work, for example. Just as often the problem is that even when the person is there in body, his or her mind is elsewhere.

Mindfulness-based CBT can address both of these issues; for example, training in mindfulness has been shown in multiple studies to increase one's ability to attend to the person we're with (as described in this previous post). A CBT framework can help translate one's intention to be present into a plan of action to make it happen.

Try it: The next time your partner talks with you about something, bring your full attention to what they're saying. Practice seeing the person as though for the first time, really focusing on them and what they're saying.

2. Less anxiety. When we're overwhelmed by anxiety, we're not our best selves. It's no surprise that untreated anxiety disorders take a toll on our closest relationships. For example, the need for a "safety companion" in panic disorder and agoraphobia can lead to strain as the supporting partner has to adjust his or her schedule to accommodate the other person's travels. Similarly the chronic worry in generalized anxiety disorder frequently leads to tension and irritability, causing conflict between partners.

For any anxiety diagnosis, the treatments with the most evidence for their effectiveness come from CBT. The relief a person feels from a marked reduction in anxiety extends to greater harmony in the relationship.

Try it: If you've struggled with uncontrollable anxiety, consider looking into the best treatments for your condition on the website for Division 12 of the American Psychological Association. You can also search the therapist directory here at PsychologyToday.com for a therapist who provides the treatment you're looking for. You might also pursue self-guided CBT, which has been shown to be effective.

3. Improved mood. As with anxiety, untreated depression wears on couples. It's a struggle to be the partner we're capable of being when we have no energy, little enthusiasm for activities we would normally enjoy, and no sex drive, among other symptoms. After a typical course of CBT for depression—12 to 16 weeks—the average person will not only feel substantially better but will be able to function much more effectively. And happier individuals make happier couples.

Try it: As with anxiety, you can search for a CBT therapist through the PsychologyToday.com therapist directory. There is also evidence that self-guided CBT can be effective for treating depression (e.g., CBT in 7 Weeks or Cognitive Behavioural Therapy).

4. Better sleep. As many as 23% of adults in the US suffered from bad sleep in the past month. When we're not sleeping well we tend to be cranky and impatient—not a recipe for the best interactions with the people who love us. Furthermore, insomnia can turn the bed into a place of worry and stress, which interferes with a cozy night's sleep beside our partner. CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) is typically 4 to 6 sessions and is the treatment of choice for insomnia. It helps a person fall asleep faster and sleep more soundly, and restores a strong association between the bed and sleep. And better sleep helps with pretty much everything.

Try it: If you've struggled with sleep, consult these guidelines for healthy sleep habits. The National Sleep Foundation has suggestions for finding a CBT-I therapist. CBT-I is also available through self-guided books (e.g., End the Insomnia Struggle) and apps.

5. Healthier relationship with alcohol. Problematic drinking can kill a relationship. Alcohol use disorder is tied to higher divorce rates, greater intimate partner violence, lower relationship satisfaction, and a host of other problems. CBT can effectively target the thoughts and behaviors that maintain problems with alcohol, and replace drinking with healthier ways of coping. Interestingly, the treatment with the strongest research evidence is Behavioral Couples Therapy, with both the patient and his or her partner actively involved in the treatment.

For many individuals with an alcohol use disorder, lifelong abstinence is necessary. However, there is modest support for a treatment program that includes the possibility of moderate alcohol consumption for some people.

Try it: If you're interested in learning more about the Moderate Drinking program, information is available here. You can also consult the PsychologyToday.com directory to find a therapist who provides Behavioral Couples Therapy for alcohol use disorders.

6. Happier kids. When a child is struggling with intense fears (e.g., phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder), it can lead to tremendous stress for the family. Parents inevitably feel the strain when a child refuses to go to school, struggles socially, or has problems at bedtime. As the saying goes, "You're only as happy as your least happy child."

Furthermore, most couples have somewhat different parenting styles, with one partner more lenient and the other more of the disciplinarian. A child's intense struggles will tend to amplify these differences, leading to conflict between the parents. At the end of the night when the kids are finally in bed and both parents just want to unwind, they may instead find themselves arguing about how best to help their child. Thus they may feel like their reserves are exhausted, with little left for their child or each other.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends CBT as a first-line approach for treating many childhood conditions, including anxiety and OCD. Similarly, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends behavioral treatments for sleep problems in infants and children, which can help both the child and the parents sleep through the night.

Try it: There are books available that detail how to apply the techniques of CBT to help your child with anxiety (e.g., Helping Your Anxious Child) or OCD (e.g., What to Do When Your Brain Gets Stuck). There are also many CBT-focused web resources available, such as from the International OCD Foundation and the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

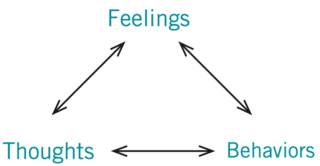

7. Healthier thought patterns. Even if we're not dealing with a diagnosable condition like anxiety, depression, insomnia, or a substance use disorder, the tools of CBT can have powerful effects on our relationships. CBT is based on an understanding of the connections among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (see figure). When our thought patterns are aligned with reality, they generally lead to positive feelings and behaviors. However, when our thoughts become distorted in some way, they start to work against us, including in our relationships.

For example, we might notice that our partner left his clothes on the floor and think, "He expects me to pick up after him. He thinks I'm his maid." The result might include a fight driven by resentment and defensiveness. Or we could think that our partner seems distant and tell ourselves, "She's unhappy with me and our relationship," leading us to withdraw in turn.

The cognitive part of CBT encourages us first of all to notice the thoughts we're telling ourselves; often they happen so quickly and automatically that we don't even recognize the story our mind is creating. Once we've identified the thoughts we can test them out to see if they're accurate. Maybe our partner's clothes on the floor say nothing about his view of us, or expectations that we clean up his mess. And perhaps our partner's preoccupation has nothing to do with our relationship and everything to do with her worries about her ailing mother. With practice we can replace distorted and destructive thoughts with more accurate and constructive ones.

(Importantly, cognitive techniques are not about fooling ourselves or pretending things are better than they are. It would be important to know if our thoughts are actually valid so we can deal with the situation directly.)

Try it: The next time you're upset with your partner, write down the thoughts you notice and the emotions you feel. Then ask yourself the following questions (adapted from Retrain Your Brain: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 Weeks):

- What is the evidence for my thought?

- Is there evidence that contradicts my thought?

- Based on the evidence, how accurate is the thought?

- How could I modify this thought to make it fit better with reality?

8. Greater enactment of our intentions. All of us want to be the best significant other we can be. We want to be attentive, supportive, generous, patient. And like anything else, the road to impoverished relationships is paved with the best of intentions. If we're not deliberate about living out our values, we risk leaving them in the abstract—vague platitudes without substance.

For example, we might tell ourselves, "My family matters to me more than anything," and then live as though family is our last priority. We might idealize presence in our relationship yet attend more to our phone than to those around us.

The tools of CBT can help even when there is no "disorder"—when we simply want to commit to sustained action that supports our deepest values. It starts with taking an inventory of our relationship, and setting clearly defined goals based on what we find—for example, To listen when my spouse talks to me. It includes identifying specific behaviors we want to practice that will move us toward our goals.

We might plan, for instance, to turn off our phone during dinner and focus on our conversation. The goals and activities can be anything important to us in our relationship: We get to decide. It can be very beneficial to collaborate with our partner in the process by asking what they need more of from us.

A CBT approach also includes planning activities as specifically as possible so they stay on our radar, like putting "Come home early to make dinner" in our calendar, and protecting the time. Through daily practice of our intentions, we give our relationship the nourishment it needs not only to last but to be extraordinary.

Try it: Can you have a conversation with your partner this week about your relationship and who you want to be for your partner? From there, make a specific plan to move toward your goals. Notice any effects on your relationship.

Wherever we are in our relationships, CBT has tools that can help align our thoughts and actions with the life we want.

Questions, comments, or other ways you've found CBT helpful for your relationship? Please leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

- Find me on the Think Act Be website and on Twitter.

- Join the official Facebook group page for CBT in 7 Weeks.

- Sign up for the Think Act Be newsletter to receive updates on future posts.

Facebook image: Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

References

Burke, L. (2003). The impact of maternal depression on familial relationships. Review of Psychiatry, 15, 243–255.

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 17-31.

Collins, R. L., Ellickson, P. L., & Klein, D. J. (2007). The role of substance use in young adult divorce. Addiction, 102, 786-794.

Gillihan, S. J. (2016). Retrain the brain: Cognitive behavioral therapy in 7 weeks - A workbook for managing depression and anxiety. Berkeley, CA: Althea Press.

Marshal, M. P. (2003). For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 959-997.

Okajima, I., Komada, Y., & Inoue, Y. (2011). A meta‐analysis on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 9, 24-34.

Powers, M. B., Vedel, E., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2008). Behavioral couples therapy (BCT) for alcohol and drug use disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 952-962.

Roth, T., Coulouvrat, C., Hajak, G., Lakoma, M. D., Sampson, N. A., Shahly, V., ... & Kessler, R. C. (2011). Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, criteria: Results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 592-600.

Schutte-Rodin, S., Broch, L., Buysse, D., Dorsey, C., & Sateia, M. (2008). Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4, 487-504.

Stuart, G. L., Meehan, J. C., Moore, T. M., Morean, M., Hellmuth, J., & Follansbee, K. (2006). Examining a conceptual framework of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 102-112.