Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy

Psychedelic Microdosing: Study Finds Benefits and Drawbacks

Microdosing DMT may have mental health benefits, a new rodent study suggests.

Posted March 4, 2019 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Microdosing psychedelics such as psilocybin (in the form of "magic mushrooms" or "magic truffles"), LSD, or DMT is a hot topic that is trending in popularity among certain subcultures around the globe. Before reporting on the latest science-based findings on microdosing, there is an important caveat: In my opinion, the uptick in recreational microdosing (and taking full doses of hallucinogens) for therapeutic purposes outside a supervised clinical setting is potentially risky.

During this early 21st-century phase of modern-day experimental research on psychedelics, it's imperative for us to exercise prudence and avoid any sensationalized "snake oil salesman" type of hype about psychedelic microdosing being the "next big thing." Much more clinical research on humans and animals is needed before scientists can pinpoint all of the potential benefits and drawbacks of microdosing various psychedelics.

That said, new state-of-the-art research (Cameron et al., 2019) in rodents unearths some potential pros and cons of microdosing DMT. These findings, by a team of scientists from the University of California, Davis, were published today.

As the authors of this paper explain, "Taken together, our results suggest that psychedelic microdosing may alleviate symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders, though the potential hazards of this practice warrant further investigation."

What Is Psychedelic Microdosing?

When microdosing a psychedelic drug, someone (i.e., the "microdoser") typically takes one-tenth the hallucinogenic dose. The growing popularity and buzz currently surrounding psychedelic microdosing stem from dubious anecdotal human testimonials—and some limited empirical evidence—suggesting that very low doses (which aren't potent enough to cause someone to hallucinate or “trip”) may boost mood, improve cognitive flexibility, stimulate creativity, and sharpen overall mental acuity.

A few months ago, I reported on an open-label natural setting human study (Prochazkov et al., 2018) which found that taking a microdose (350 milligrams) of psychedelic truffles boosted divergent thinking, creativity, and out-of-the-box problem-solving abilities.

Whenever I report on the potential upside of using psychedelic drugs (see here and here) in a clinical setting, I’m cautious about being overzealous or appearing to condone the use of hallucinogenic drugs.

Anecdotally, my trepidation and "proceed with caution" advice about ingesting any psychedelic drug is primarily based on my reckless experimentation with magic mushrooms during adolescence.

Clinical research and autobiographical evidence reaffirm that the dose of a psychedelic drug in relation to body weight (in both humans and animals) makes a dramatic difference on how the mammalian body, mind, and brain respond to a hallucinogen.

Based on first-hand life experience, I learned the hard way about the importance of being hyper-vigilant about closely monitoring and personalizing psychedelic dosages—based on your body weight, amount of food in your stomach, and overall sensitivity to drugs—prior to ingesting any type of psychedelic drug or hallucinogen.

For example, the first time I took psilocybin, I knew nothing about dosing. Luckily, I ingested a "Goldilocks" amount of not too much/not too little and experienced a life-empowering hallucinogenic trip. As a first-timer, the dosage of magic mushrooms I consumed led to a blissful and ego-dissolving mystical experience that allowed my entire being to meld with the “oneness” of everything in the surrounding environment (and wider universe). I know ... this sounds woo-woo. But it was profoundly life-changing and something I don't regret.

The "transcendent ecstasy" of my first psychedelic experience opened my eyes to the tangible existence of higher states of consciousness. However, the potential dark side of psilocybin inspired me to pursue drug-free ways to let go of my ego and create peak states of “superfluidity” marked by zero friction, viscosity, or entropy between one’s thoughts, actions, and emotions.

The second time I took magic mushrooms, I was still clueless about the vast difference between megadosing vs. microdosing. Unwittingly, I scarfed down a "mega dose" of psilocybin (which I estimate was more than five grams of dried mushrooms). This dosage blew my mind and resulted in a terrifying, PTSD-inducing “bad trip” that still haunts me four decades later. As I describe in my first book:

I don’t know if you’ve ever had a bad trip, but it feels like all the tumblers in your brain are turning and reconfiguring; unlocking doors that should stay shut, closing windows that should stay open, all the while re-etching the blueprints of your psyche and the foundation of your soul. Psilocybin fuses your synapses into new configurations, permanently rearranging the architecture of your mind. –Christopher Bergland in The Athlete’s Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss

Microdoses of DMT May Produce Positive Effects on Mood and Anxiety

One reason for sharing my own experience with the “pros and cons” of psychedelics is that the above-mentioned study by researchers at UC Davis found that microdosing DMT has two potential benefits, but also has negative effects.

Their paper, "Chronic, Intermittent Microdoses of the Psychedelic N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) Produce Positive Effects on Mood and Anxiety in Rodents,” was published March 4 in the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience.

This pioneering psychedelic microdosing research was led by senior author David Olson, who is an assistant professor in the UC Davis departments of Neuroscience, Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Molecular Medicine. He's also founder and principal investigator of the eponymous Olson Lab.

Notably, another “neutralizing” aspect of the new research by Olson and his team was that microdosing DMT did not seem to improve or impair cognitive function or sociability among lab rats. This finding may debunk anecdotal human "microdoser" claims about such benefits, but more research is needed.

"Prior to our study, essentially nothing was known about the effects of psychedelic microdosing on animal behaviors," Olson said in a statement. "This is the first time anyone has demonstrated in animals that psychedelic microdosing might actually have some beneficial effects, particularly for depression or anxiety. It's exciting, but the potentially adverse changes in neuronal structure and metabolism that we observe emphasize the need for additional studies."

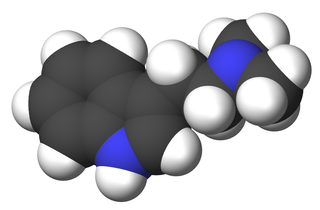

In an earlier paper (Cameron & Olson, 2018), Lindsay Cameron and David Olson give a detailed description of what makes DMT unique:

Though relatively obscure, N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is an important molecule in psychopharmacology as it is the archetype for all indole-containing serotonergic psychedelics. Its structure can be found embedded within those of better-known molecules such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin. Unlike the latter two compounds, DMT is ubiquitous, being produced by a wide variety of plant and animal species. It is one of the principal psychoactive components of ayahuasca, a tisane made from various plant sources that has been used for centuries. Furthermore, DMT is one of the few psychedelic compounds produced endogenously by mammals, and its biological function in human physiology remains a mystery.

For their most recent DMT experiments (2019), the researchers in Olson's Lab administered a "microdose" equivalent to one-tenth of what they estimated to be a hallucinogenic dose of this psychedelic drug in a cohort of lab rats approximately every 72 hours for two months.

The researchers emphasize that there isn't a universal standard or well-established protocol for what constitutes an appropriate microdose of any given psychedelic. (Hence the need to always proceed with caution when taking hallucinogens.) For this experiment, the researchers followed the guesstimate guidelines of 1/10th a “trip” dose based on the bodyweight of each lab rat.

After two weeks of receiving a microdose of DMT every third day, Olson and his team began conducting behavioral tests on the rats during the two days between microdoses. These animal-based lab tests are designed to mimic how a drug might affect cognitive function, mood, and anxiety for humans in the real world.

Olson’s group found that microdoses of DMT in rodents had two potential benefits:

- Anxiety: DMT microdosing appeared to help lab rats overcome a conditioned "fear response" in a behavioral test that is considered to be a laboratory model that mirrors post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other fear-based anxiety disorders in humans.

- Depression: In an experiment that is designed to measure the effectiveness of antidepressant compounds, the researchers found that microdosing DMT caused rats to move around more and reduced their immobility. In animal models, less immobility is considered to be a sign that an antidepressant compound is working.

As mentioned earlier, when the UC Davis researchers tested cognitive function and sociability in rats taking microdoses of DMT, they did not observe any apparent impairments or improvements. This animal-based finding contradicts some anecdotal reports of human cognition and social behaviors benefiting from psychedelic microdoses in real-world situations. Again, more research is needed.

On the downside, the authors found two potential risks associated with microdosing DMT:

- Metabolism. The male rats who were given a microdose of DMT for two months experienced a significant increase in body weight.

- Neuronal Structure. In an unexpected finding, Olson’s group found that microdoses of DMT were associated with neuronal atrophy in female rats. This surprised the researchers because a previous study (Ly et al., 2018) in their lab found that rats who were given a single, higher “hallucinogenic” dose of DMT displayed an increase of neuronal growth.

“The results suggest an acute hallucinogenic dose and chronic, intermittent low doses of DMT produce very different biochemical and structural phenotypes,” Olson said.

One of the most promising aspects of the Olson Lab's latest research on microdosing DMT is that these findings suggest the possibility of decoupling the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelic drugs from the therapeutic properties of their compounds.

"Our study demonstrates that psychedelics can produce beneficial behavioral effects without drastically altering perception, which is a critical step towards producing viable medicines inspired by these compounds," Olson concluded.

References

Lindsay P. Cameron, Charlie J. Benson, Brian C. DeFelice Oliver Fiehn, and David E. Olson. "Chronic, Intermittent Microdoses of the Psychedelic N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) Produce Positive Effects on Mood and Anxiety in Rodents." ACS Chemical Neuroscience (First published online: March 4, 2019) DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00692

Luisa Prochazkova, Dominique P. Lippelt, Lorenza S. Colzato, Martin Kuchar, Zsuzsika Sjoerds, Bernhard Hommel. "Exploring the Effect of Microdosing Psychedelics on Creativity in an Open-Label Natural Setting." Psychopharmacology (First published online: October 25, 2018) DOI: 10.1007/s00213-018-5049-7

Lindsay P. Cameron and David E. Olson. "Dark Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT)" ACS Chemical Neuroscience (First published online: July 23, 2018) DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00101

Calvin Ly, Alexandra C. Greb, Lindsay P Cameron, Jonathan M Wong, Eden V. Barragan, Paige C. Wilson, Kyle F. Burbach, Sina Soltanzadeh Zarandi, Alexander Sood, Michael R. Paddy, Whitney C. Duim, Megan Y Dennis, A. Kimberley McAllister, Kassandra M. Ori-McKenney, John A. Gray, David E. Olson. "Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity." Cell Reports (First published: June 12, 2018) DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022.

Lindsay P. Cameron, Charlie J. Benson, Lee E. Dunlap, and David E. Olson. "Effects of N,N-Dimethyltryptamine on Rat Behaviors Relevant to Anxiety and Depression." ACS Chemical Neuroscience (First published online: April 17, 2018) DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00134.