Resilience

How to Build Resilience During the Post-Pandemic Transition

Being flexible is key to coping with uncertainty.

Posted April 27, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- During the past year, COVID-19 has been a chronic stressor. Research has shown that chronic stressors can be psychologically challenging.

- The confusion and stress of the pandemic have damaged many people's confidence in their own capabilities and ability to make good decisions.

- The science of emotion—and in particular, psychological flexibility—can provide an anchor and compass in navigating this unsettling journey.

This post was written by Robert M. Gordon, Psy.D., and Jed N. McGiffin, Ph.D. Dr. Gordon is a member of the Medicine & Addictions workgroup (established by 14 divisions of the American Psychological Association) that sponsors this blog.

During the past year, COVID-19 has been a chronic stressor, which research has shown to be more psychologically challenging than acute adversity events (Bonanno & Diminich, 2013).

Numerous factors have made COVID-19 potentially traumatic for individuals, including persistent anxiety about being both the agent spreading the virus and the victim of it, the prolonged state of vulnerability and uncertainty as to when the pandemic will end, collective grief and loss, social isolation, and the disruption of daily life (Gordon et al., 2020). The pandemic has precipitated an acute awareness of the fragility of life and aspects of our life that were previously taken for granted (Gold & Zahm, 2020).

In the aftermath of chronic stress or adversity, individuals typically undergo a transition period that involves readjusting to a state of relative safety and adapting behaviors accordingly.

There are a number of unique features of the transition phase. While we are no longer in the acute early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, neither are we in a post-pandemic world. There is a sense of uncertainty of “standing in the spaces” between different identities (Bromberg, 1998). In certain situations, we may feel confident and more like our “old self,” but at other moments, we may experience a lack of confidence—especially when judging which decisions are safe. Much of the tension during the transition phase comes from the anxiety that we are not getting it right, and we may fear that changing patterns and coping strategies developed during the pandemic might be too risky (Shea, 2021).

These psychological challenges have left many individuals feeling unsettled about how best to move forward during this time of uncertainty and unsure what psychological skills might facilitate inner strength and a sense of agency (Shea, 2021). The science of emotion—and in particular psychological flexibility—can provide an anchor and compass in navigating this unsettling journey.

Flexibility as a Mechanism for Resilience

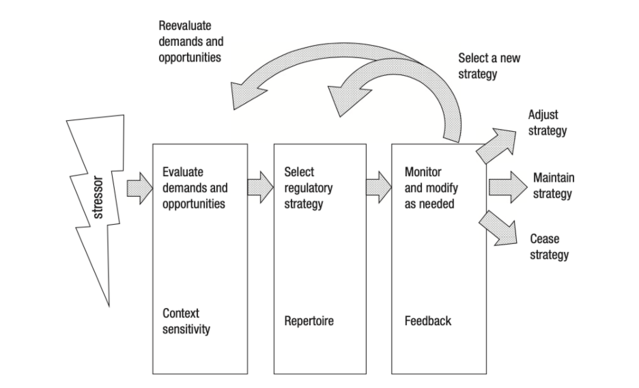

Psychological flexibility is an important and modifiable predictor of resilience and has even been proposed as an explanation for how resilience works (Bonanno, 2021a; Bonanno, 2021b). Being flexible in the midst of a life stressor has been described as a sequence of three stages (Bonanno & Burton, 2013):

- Evaluating the demands of the situation or context

- Selecting a response or coping strategy

- Monitoring the success of an approach and modifying as needed (Bonanno et al., 2013)

Facilitators of Flexibility and Resilience

What then, can we do to improve psychological flexibility and resilience during the current time of transition? At least one answer lies in creating the optimal conditions for being flexible.

Both resilience and flexibility are facilitated by several constructs, such as hope, optimism, grit, perseverance, and mindfulness. These traits indirectly influence outcomes by providing internal resources and increasing motivation for flexibility and problem solving (Bonanno, 2021a).

Hope and Optimism

Hope and optimism are two psychological constructs that focus on an individual’s beliefs about the future (Rabinowitz et al., 2018). While optimism is a stable personality state related to a sense that good things will happen in the future, hope involves the will to effect positive outcomes and the ability to generate flexible problem-solving strategies when facing obstacles to achieve desired goals (Rabinowitz et al., 2018).

Grit and Perseverance

Grit is a personality construct initially described by Angela Duckworth and colleagues as perseverance, persistence, and passion toward long-term goals (Duckworth et al, 2007). Grit enables individuals to engage in effortful activities including studying or exercising, particularly when practicing may not be intrinsically rewarding (Duckworth et al., 2011; Rabinowitz et al., 2018).

Mindfulness

Mindfulness involves the ability to be open and to observe rather than judge or “push away” thoughts and feelings (Harris, 2018). Being mindful enables us to appreciate our common humanity and to reflect on the present moment with awareness, self-compassion, and perspective (Germer et al., 2013).

Strategies to Develop Flexibility During the COVID-19 Re-Entry Phase

The following tips are related to improving psychological flexibility and resilience:

- Cultivate optimism. Questions including “What have you discovered about yourself through the pandemic?” and “Are you aware of any aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic that has changed you for the better?” allow one to construct a more flexible and self-compassionate narrative (Gordon et al., 2020).

- Make a list of things you can and cannot control.

- Accept events as they actually happen during the transition and focus on your reactions and attitudes.

- See your struggles as part of the human condition rather than an isolated experience.

- Your decisions during the transition phase should be consistent with your most important values, what kind of person you want to be, and long-term goals (Harris, 2018).

- Consider context—determine whether you are appraising the situation accurately, then adjust your coping strategy to match the situational demands.

- Self-monitor and give feedback. After trying a strategy, ask yourself “How well is what I am doing working?” “Could I try something else that might work better?”

Concluding Thoughts

Making time to cultivate mindfulness, optimism, and hope can provide the motivation for flexible coping and resilience during the pandemic transition, while harnessing our inner perseverance and grit can help us not give up when we realize that our previous approach to the threat needs to change.

Robert M. Gordon, Psy.D. is the Director of Intern Training and Associate Director of Postdoctoral Fellow Training at Rusk Rehabilitation and Clinical Associate Professor at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Dr. Gordon has specialties in the areas of neuropsychological and forensic testing and psychotherapy with children and adults with physical and learning disabilities and chronic illness. Dr. Gordon is a member of the COVID Psychology Task Force (est. by 14 divisions of the American Psychological Association working group: Hospital, Healthcare, and Addiction Workers, Patients, and Families that sponsor this blog.

Jed N. McGiffin, Ph.D. received his doctorate in clinical psychology at Teachers College, Columbia University under the research mentorship of Dr. George A. Bonanno in the Loss, Trauma, and Emotional Lab. He has research interests at the intersection of psychology and medicine, including the psychological impact of acute medical events and more broadly the process of psychological adjustment to disability.

References

Bonanno, G. A., & Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504116

Bonanno, G. A., & Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual Research Review: Positive adjustment to adversity—Trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 378–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12021

Bonanno, G. A. (2021a). The resilience paradox. European Journal of Psychotraumatology.

Bonanno, G. A. (2021b). The end of trauma: How the new science of resilience is changing how we think about PTSD (1st ed). Basic Books, Inc.

Bromberg, P. M. (1998). Standing in the spaces: Essays on clinical process, trauma, & dissociation. The Analytic Press.

Germer, C. K. & Neff (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 69(8), 856-867. http://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22021

Gold, E. & Zahm, S. (2000). Buddhist psychology informed gestalt therapy for challenging times. The Humanistic Psychologist, 48(4), 373-377. http://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000213

Gordon, R. M., Dahan, J. F., Wolfson, J. B., Fults, E., Lee, Y. S. C., Smith-Wexler, L., Liberta, T. A., & McGiffin, J. N. (2020). Existential-humanistic and relational psychotherapy during COVID-19 with patients with preexisting conditions. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. Published online: November 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820973890

Harris, R. (2018). The happiness trap: How to stop struggling on start living. Trumpeter Books.

Rabinowitz, A. R., & Arnett, P.A. (2008). Positive psychology perspective on traumatic brain injury recovery and rehabilitation. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. 25(4), 295-303. https://doi.org/0.1080/23279095.2018.1458514

Shea, L. M. (2021). The courage to be: Using DBT skills to choose who to be in uncertainty. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(1), 260-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820950887