Law and Crime

Why Defense Forensics Experts Matter

The presentation of forensic evidence is typically one-sided.

Posted April 11, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- At criminal trials, a defense expert can change how jurors view evidence.

- A defense expert who does not offer contrary conclusions can still affect how jurors perceive the methodology.

- A true battle of the experts could give a jury more information about the strengths and limitations of forensic evidence.

Courtroom dramas play up the idea of criminal trials as a hard-fought contest between the prosecution and the defense. The prosecutor, representing the state, tries at all costs to secure a conviction of the defendant, who is represented by a skillful, underdog defense counsel. The prosecutor may call expert witnesses, who may sway the jury with their credentials and crime lab technology. The defense, however, typically relies on more family or alibi witnesses. There is a courtroom battle, but no battle of the experts.

That much about courtroom dramas is fairly accurate. The presentation of forensic evidence is typically one-sided. Judges often refuse requests from indigent defendants to hire their own expert, particularly in state courts. Indeed, few cases proceed to a criminal trial, and without an expert of their own, the defense may have little way to assess any forensic reports. When cases do go to trial, the defense cannot present their own expert's view of the evidence.

What happens if the defense actually gets an expert?

In a recently published article, Gregory Mitchell and I conducted a “battle of the experts” experiment to see what would happen if mock jurors heard from a defense expert, and not just a prosecution fingerprint expert. These jurors watched a video of a fingerprint expert for the prosecution and found it very compelling: most would convict a defendant just based on that short video.

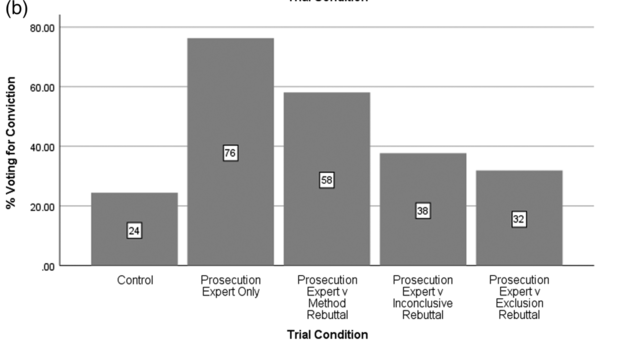

However, when they saw a video of a defense expert, everything changed. The figure below shows the rates at which these mock jurors convicted.

If the defense expert reached a different conclusion, such as that the evidence was inconclusive, jurors were far less likely to convict the defendant. The defense expert helped to neutralize the prosecution fingerprint evidence. The figure above shows how many fewer people voted for a conviction when the defense expert said that the evidence was inconclusive, contradicting the prosecution expert, and how many fewer people voted for a conviction when the defense expert said the evidence actually excludes the defendant. To be sure, it is troubling that over one-third would still convict, where an expert with equal experience and credentials tells them that the defendant could not have been the one who left the fingerprint.

How often might a separate expert come to a different conclusion in a real criminal case? We do not know, but we do know that expert conclusions vary when forensic experts are given realistic case materials.

We also learned from this study that just having a defense expert re-explain how fingerprint methods work had a real impact on conviction rates. In the figure, this is referred to as a methodological rebuttal. There, the defense expert discussed the difficulties that can arise from the subjective examination of latent prints and summarized academic studies on error rates in fingerprint identification. That type of defense expert caused many mock jurors to view the prosecution's case as substantially weaker and made them significantly less likely to vote to convict.

Traditionally, a vigorous cross-examination is seen as enough. Judges often deny the defense funding for an expert, by noting that they can simply question the prosecution expert. We emphasized that:

Even when cross-examination is effective at raising doubts about an expert's opinions, it will rarely bring out directly contrary evidence of the kind that a rebuttal expert can present. Our results suggest that the use of a rebuttal expert will be a more effective and reliable way of educating jurors about the limits of fingerprint evidence because this method permits parties to use a central route to persuasion: by focusing juror attention on a rebuttal expert, the defendant can present information that raises questions about the fallibility of fingerprint evidence in general and about the government's fingerprint evidence in the case at hand.

Judges should reconsider their traditional reluctance to appoint defense experts. Laypeople place extremely strong weight on fingerprint evidence. People assume a fingerprint match is infallible, even though error rates are far higher than what people commonly suppose. And yet, jurors can place more appropriate weight on fingerprint evidence if they hear from experts on both sides.

A true battle of the experts can give the jury far more information about the strengths and the limitations of forensic evidence. It raises serious fairness concerns, in my view, to so routinely deny the defense the tools needed to respond to forensic experts. The one-sided presentation of forensic evidence is manifestly unjust and it should end.

References

Mitchell, G, Garrett, BL. Battling to a draw: Defense expert rebuttal can neutralize prosecution fingerprint evidence. Appl Cognit Psychol. 2021; 1– 12. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3824