Loneliness

The Neuroscience of Loneliness

In this hyperconnected society that we live in, loneliness is an epidemic.

Posted December 19, 2017

Loneliness is an epidemic. We are going through times of profound social change, and the Internet and other new social technologies are huge drivers of this epidemic, allowing us to remain in touch with others without actually having to connect with them.

Humans, like it or not, are social mammals. We need to interact with each other, and as a society, we tend to organize ourselves in communities. Loneliness — another term for social isolation — is nothing new. Authors have written about it for centuries, but it is a lot more than a source of inspiration for the arts; it is a biological mechanism that pushes people to find the social interaction that they lack and need. The brain will push the lonely individual to find someone to interact with, because, again, we are social mammals. We need company because our prehistoric ancestors desperately required company in order to survive; the presence of other human beings ensured protection and support, both for themselves and for their offspring. Our brains still think we need to be surrounded by others to survive and thrive.

Of course, loneliness is also a natural feeling that everyone experiences at some point in their life. But a chronic state of social isolation is linked to depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). These are real threats to members of the groups most vulnerable to social isolation, who are so often overlooked in terms of mental health.

Google “epidemic loneliness” and you will find that many people have already asked such questions as: Can someone die of loneliness? This may seem over the top, but the question has been raised, and loneliness is in fact starting to be considered as a public health concern. But what is the physiological mechanism of feeling lonely? And can loneliness actually kill us?

Research has been published to shed some light on these issues. Researchers have found that social isolation affects the activation of dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons, which are key to our emotional well-being.

Matthews and collaborators found that dopaminergic neurons in a brain region called the dorsal raphe nucleus were activated in response to acute social isolation and triggered the motivation to search for and re-engage in social interactions.

They studied mice that were either housed together or isolated, and tracked their reactions when they were introduced to a new mouse. Mice that had been isolated until that point showed remarkably high activity in that brain region, which motivated them to interact with the new mouse in the cage. On the other hand, mice that were already interacting with other mice (i.e., the mice housed together) showed a lack of interest in the new kid on the block.

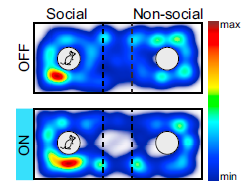

To measure sociability, they used a well-known protocol to study social interactions: the three-chambers test. In this protocol, the mouse is placed in a cage with three different sections. One of them is the so-called “social section,” where another mouse is in place. We expect that the studied mouse (which starts from the central section of the cage) will spend more time exploring the social section and interacting with the new mouse, rather than isolating itself in the non-social section of the cage. Because, like us, mice are social mammals. By the power of optogenetics, the researchers played with the photoactivation of the dopaminergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus. They were able to switch the neurons “on and off” at will and study the changes. The researchers found that when these neurons were "on," the mouse spent more time in the social section of the cage, showing an increase in its motivation for sociability.

Interestingly, they also observed aversive behavior when the dopaminergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus were activated, but the studied mouse was deprived of the possibility of a social interaction (i.e., the new mouse in the social section was absent). In another experiment, the mouse avoided the section of the cage where it received light stimulation, having learned to relate light to the “lonely feeling.” And due to the absence of another mouse, there would be no relief to its loneliness.

All of these results indicate that neuronal connections are potentiated following social isolation, which makes an individual seek the social interaction that they lack. The researchers concluded that the activation of the dopaminergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus is only necessary for isolated individuals, since those are the ones that need social interaction the most.

They compare the craving of company in socially isolated individuals to hunger states that trigger the search for food. Since different neural circuits are involved in the consumption of food because it is yummy, or because we are hungry, they hypothesize that a similar situation applies to social interactions, and speculate that different neural circuits may be at play when the subject wants social interaction because it is either rewarding (yummy), or because they feel lonely (hungry).

Sargin and collaborators came to similar conclusions after looking at serotonergic neurons instead of dopaminergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus in response to social isolation. They identified the SK channels accountable for the alterations in serotonergic neurons after chronic social isolation. So when they blocked these channels, they could treat the anxiety-like and depressive behaviors in the isolated mice (e.g., eating disorders and decreased mobility).

Loneliness, as pretty much all of us feel, is controlled by the brain. Although loneliness is considered a negative feeling, science shows that it is actually something we need in order to overcome a situation that may put us at a disadvantage. Just like feeling physical pain, this is the way your body tells you there is something wrong. So, loneliness cannot kill us per se, but if it is not mitigated, it might trigger anxiety, stress, and depression, which are known to drive people to unfortunate outcomes.

The next time you feel lonely, think about your dorsal raphe nucleus. The neurons there are just trying to help you out; listen to them. Find your social interactions, and give those neurons a break.

This post was originally published in NeuWrite San Diego.

References

The Evolution of Anxiety and Social Exclusion. Buss, D.M. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 9, 196–201. 1990.

Old Age and Loneliness Renee P. Meyer, MD and Dean Schuyler, M. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011; 13(2): e1–e2.

Dorsal Raphe Dopamine Neurons Represent the Experience of Social Isolation, Gillian A. Matthews, Edward H. Nieh, Caitlin M. Vander Weele, Sarah A. Halbert, Roma V. Pradhan, Ariella S. Yosafat, Gordon F. Glober, Ehsan M. Izadmehr, Rain E. Thomas, Gabrielle D. Lacy, Craig P. Wildes, Mark A. Ungless, Kay M. Tye. Cell, Volume 164, Issue 4, 11 February 2016, Pages 617-631, ISSN 0092-8674, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.040.

Chronic social isolation reduces 5-HT neuronal activity via upregulated SK3 calcium-activated potassium channels. Sargin D, Oliver DK, Lambe EK. 2016 Nov 22.