Cognition

When You See Objects, You Think Words

Vision and language are tightly interconnected

Posted June 23, 2015

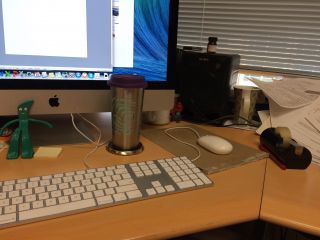

Take a quick look around the room. Chances are, you looked at a number of different objects. From where I am sitting, there is a computer, a coffee mug, a tape dispenser, and a little green Gumby model.

In order for me to describe this scene to you, I had to take the glance around the room and turn it into a description using words for the objects that I saw. If I didn’t have the goal to communicate this information to you, though, would I still have thought of the words for each of these objects?

That question was explored in a clever study by Sarah Chabal and Viorica Marian in the June, 2015 issue of the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

These researchers examined what people looked at when searching for an object. Luckily for experimental psychologists, you only have a small window of clear vision in your eyes. If you hold your thumb out at arm’s length and look at the nail, that is about the size of the high quality vision you get from your eyes. That central part of the retina at the back of your eye is densely packed with light-sensitive cells. The rest of the retina is less densely packed, and so the quality of what you see outside of that focus is less clear.

As a result, you are constantly moving your eyes around to take in new information. There are devices (called eye trackers) that measure where you are looking. You can use that information to get a sense of how people are taking in information over time.

Chabal and Marian showed people a line drawing of an object (like a clock) and asked them to search for that same drawing in a display containing four objects. This is a fairly easy task for people to do.

On some trials, though, the word that would describe one of the other objects in the display shared letters (and speech sounds) with the word for the target object. So, when searching for a clock, the display would also contain a cloud. Notice that no words are being used in this study. Participants see a picture and then search for that picture in the next display.

People glance at all four objects in the display when searching for the target picture, but if there is an item that shares letters with the target, they look at that item much more than any of the other items that are not the target. When searching for a clock, people also focus their eyes on the cloud. This finding suggests that when people see each item, they are automatically thinking about the word that would describe that object.

So far so good. But maybe there is some hidden connection between these items that causes people to look at both. To control for this possibility, the researchers also ran a group of English-Spanish bilinguals. The materials were designed so that some of the trials had items that shared letters with the target object in Spanish, but not in English. For example, the Spanish word for clock is reloj. The display might also contain a picture of a gift (which is regalo in Spanish).

Like the English speakers, the English-Spanish bilinguals shown a display with a clock and a cloud looked at both objects quite a bit. The bilinguals shown a display with a clock and a gift also looked at those objects extensively. The English speakers, though, did not look at the gift very much when they saw that display. Because the words clock and gift do not share letters or sounds, the gift was not a tempting alternative when searching the display.

There are two interesting aspects to these results. First, it is fascinating that just looking around the world leads you to think about the words you would use to describe the situation.

The second interesting thing is that we are prone to use a medium level of abstraction when identifying words. You can use lots of different words for any object you see. A particular clock might be described as a grandfather clock, a clock, a timepiece, or an object. The psychologist Eleanor Rosch and her colleagues in the 1970s noticed that people tend to focus on a medium level of abstraction (clock) rather than a very specific or a very general word when they first identify an object.

It is handy to be thinking of words as we see objects for several reasons. First, we often have to describe things in the world around us, so preparing to use words for things we see helps save time when we are talking to others. Second, language is a useful tool for helping us to remember things. If I ask you to remember a picture for a few minutes, it is helpful to remember what the object looks like, but using the word for the object provides another way to remember what you were told to find.

Follow me on Twitter.

And on Facebook and on Google+.

Check out my new book Smart Change.

And my books Smart Thinking and Habits of Leadership

Listen to my radio show on KUT radio in Austin Two Guys on Your Head and follow 2GoYH on Twitter and on Facebook.