Spirituality

The Rainbow's Promise

Lawrence's novel is about a spiritual awakening.

Posted April 28, 2021 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

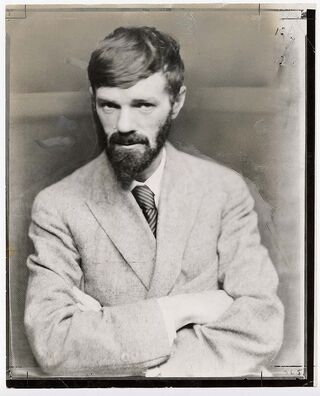

D. H. Lawrence is best known for Lady Chatterley's Lover, in which a woman is awakened to herself through sexual experience. The Rainbow, published in 1915, is also about a woman's awakening but to much more than herself. It is a spiritual awakening.

A long novel, The Rainbow concerns three generations of a rural family, the Brangwens. At the start, looking back to even earlier times, they are a humble dynasty of farmers in a remote Nottinghamshire valley where the pace of life is gentle. Here, the seasons' and years' coming and going are marked by the regularity of the church bell and the liturgy of the church calendar. The first intrusion is the arrival of a young Polish widow, Lydia, and her child, Anna, who both, in turn, marry stolid Brangwen men. Ursula Brangwen is the firstborn child of Anna and her husband, Will.

When Ursula appears, industrialisation is already having an appreciable effect on valley life. The local coalfields are being exploited. Factories appear, and townships are expanding into ugly suburbs as people flock from the countryside to work. Farms are increasingly mechanised. Canals and railways are constructed to carry coal, raw materials, and factory-finished products to their destinations. Attitudes, values and priorities change, and Lawrence is critical, referring to the commercial takeover as, "Corruption triumphant and unopposed," describing too, for example, "The blackened hills opposite, the dark blotches of houses, slate-roofed and amorphous, the old church-tower standing up in hideous obsoleteness above raw new houses on the crest of the hill."

Of the teenage Ursula, he says, "The girl had come to the point where she held that that which one cannot experience in daily life is not true for oneself... So the old duality of life, wherein there had been a weekday world of people and trains and duties and reports, and besides that a Sunday world of absolute truth and living mystery... this old, unquestioned duality suddenly was found to be broken apart. The weekday world had triumphed over the Sunday world." It is a kind of lament.

In the same passage, we read, "As Ursula passed from girlhood towards womanhood, gradually the cloud of self-responsibility gathered upon her. She became aware of herself, that she was a separate entity in the midst of an unseparated obscurity, that she must go somewhere, she must become something." This dawning of self-awareness marks an important step on the road to spiritual maturity, out of conformity into individuality. People are drawn both ways: to conform in thinking and behaviour within society, to stay safe; alternatively to become independent, exercising personal choice. The latter, however, carries risks of isolation, especially when acknowledging the accompanying responsibility, as does Ursula. Lawrence describes her reaction: "She was afraid, troubled. Why, oh why must one grow up, why must one inherit this heavy, numbing responsibility of living an undiscovered life? Out of the nothingness and the undifferentiated mass, to make something of herself! But what? In the obscurity and pathlessness to take a direction! But whither? How to take even one step? And yet, how stand still? This was torment indeed, to inherit the responsibility of one's own life..."

Ursula experiences doubt of an extreme but necessary kind; necessary for growth to proceed. "The religion which had been another world for her, a glorious sort of play world... now fell away from reality, and became a tale, a myth, an illusion, which, however much one might assert it to be true, an historical fact, one knew was not true — at least, for this present-day life of ours... The Sunday world was not real, or at least, not actual. And one lived by action... Only the weekday world mattered... Her soul must have a weekday value, known according to the world's knowledge... One was responsible to the world for what one did. Nay, one was more than responsible to the world. One was responsible to oneself." And, of course, there is no Sunday world anymore. Trading continues 24/7.

When Ursula was born, her mother had experienced something similar but had retreated into motherhood. "Anna loved the child very much, oh very much. Yet still she was not quite fulfilled... What could she see? A faint, gleaming horizon, a long way off, and a rainbow like an archway, a shadow door with faintly coloured coping above it. Must she be moving thither?... Dawn and sunset were the feet of the rainbow that spanned the day, and she saw the hope, the promise. Why should she travel any further?... And soon she again was with child. Which made her satisfied and took away her discontent... She was a door and a threshold, she herself. Through her another soul was coming." But Ursula would not accept this conventional solution. She is attracted to men, and they to her. Nevertheless, she will not be a "social wife." She cannot accept their proposals: "She liked Anthony, though. All her life, at intervals, she returned to the thought of him and of that which he offered. But she was a traveller, she was a traveller on the face of the earth, and he was an isolated creature living in the fulfilment of his own senses... Ultimately and finally, she must go on and on, seeking the goal that she knew she did draw nearer to."

The symbol of that goal is the rainbow. By recounting the biblical story in which Noah, after surviving the great flood, receives divine assurance in the covenant of the rainbow, Lawrence asserts this glory of nature as a deliberately spiritual symbol. However outdated the church buildings have become by the beginning of the twentieth century, as the book draws to its close, the rainbow still promises hope. Ursula must eventually face the proposal of her long-time lover, Skrebensky, a soldier with the Royal Engineers, who, despite their undoubted and powerful mutual attraction, "Somehow, had created a deadness round her, a sterility, as if the world were ashes... At the bottom of his heart his self, the soul that aspired and had true hope of self-effectuation lay as dead, still-born, a dead weight in his womb... He was just a brick in the great social fabric, the nation, the modern humanity. His personal movements were small. and entirely subsidiary. The whole form must be ensured, not ruptured, for any personal reason whatsoever, since no personal reason could justify such a breaking. What did personal intimacy matter? One had to fill one's place in the whole, the great scheme of man's elaborate civilisation, that was all."

He is too predictable, and Ursula, responding to her own soul's relentless drive to live and breathe independently, cannot accept him. Utterly torn, sending him finally away, she reaches a crisis in which she falls seriously ill to the point of becoming delirious. Her eventual recovery marks a turning point, an epiphany, as the final climax approaches: "As she grew better, she sat to watch a new creation... In everything she saw she grasped and groped to find creation of the living God, instead of the old, hard barren form of bygone living... She saw the stiffened bodies of the colliers, which seemed already enclosed in a coffin, she saw their unchanging eyes, the eyes of those who are buried alive: she saw the hard cutting edges of the new houses, which seemed to spread over the hillside in their insentient triumph, the triumph of horrible, amorphous angles and straight lines, the expression of corruption triumphant and unopposed..."

Then we have the rainbow. "In the blowing clouds, she saw a band of faint iridescence colouring in faint colours a portion of the hill. And forgetting, startled, she looked for the hovering colour and saw a rainbow forming itself... Steadily the colour gathered, mysteriously, from nowhere, it took presence upon itself till it arched indomitable, making great architecture of light and colour and space of heaven, its pedestals luminous in the corruption of new houses on the low hill, its arch the top of heaven... And the rainbow stood on the earth. She knew that the sordid people who crept hard-scaled and separate on the face of the world's corruption were living still, that the rainbow was arched in their blood and would quiver to life in their spirit, that they would cast off their horny covering of disintegration, that new, clean, naked bodies would issue to a new germination, to a new growth, rising to the light and the wind and the clean rain of heaven. She saw in the rainbow the earth's new architecture, the old, brittle corruption of houses and factories swept away, the world built up in a living fabric of Truth, fitting to the overarching heaven."

With these final apocalyptic words, Lawrence reveals this, the quest of one woman, a fallible human being, to be full of hope, seamlessly and gloriously linking earth and heaven, time and eternity, nature and all humankind. In a time of dominant and often corrupt materialism, increasing technological wizardry, devastating eco-destruction and climate change, Ursula's spiritual vision is surely one to seek, discover and realise for ourselves as we each awaken and learn how to take increasing responsibility for our individual and collective destiny on this fragile and beautiful planet.

Copyright Larry Culliford