Coronavirus Disease 2019

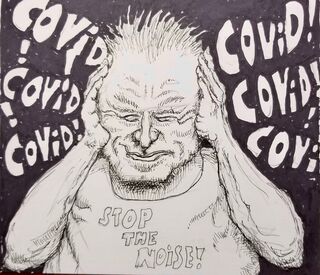

Tinnitus: Another Symptom of COVID-19?

While the link is unclear, new research offers hope for sufferers.

Posted June 18, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Tinnitus-related queries skyrocket as COVID-19 patients report related symptoms.

- An accidental discovery during a deep-brain stimulation experiment may have a potential solution.

- A new therapy based on brain/auditory stimulation indicates significant reduction in tinnitus symptoms and is worthy of further research.

One of the many ironies of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the relative quiet that has settled on usually noisy human environments, despite the crisis, and the resultant feeling of well-being associated with such calm. New Yorkers accustomed to the crash and whine of traffic and the near-constant shriek of jetplanes landing or taking off suddenly heard birds singing and squirrels chattering in streets where, before the pandemic, noise from human machinery had overwhelmed everything else.

But such solace has not been granted to everyone. One group relatively impervious to the drop in noise is the estimated 15 percent of the population suffering from tinnitus, the condition whereby a person experiences constant noise in their ears—noise that is generated not externally but from within.

A report from the British Tinnitus Association states that COVID-19 has exacerbated tinnitus generally, noting that webchats associated with tinnitus symptoms increased by 256 percent from May to December 2020 compared to the previous year while calls to its helpline rose by 16 percent. Online searches for "tinnitus causes" in the UK nearly doubled in February 2020 compared to the previous February.

At the same time, a study run by the University of Manchester, also in the UK, concluded that 14.8 percent of COVID-19 patients in Germany and the Republic of Ireland reported tinnitus as a function of the disease. Those data must be treated with caution, however, given that the study did not ascertain whether these were new cases of tinnitus or aggravations of old ones. It is also unclear whether the tinnitus symptoms were associated with the virus or with the medications used to treat it.

But given the prevalence of tinnitus and the extent to which constant, unwanted noise in the ears can pollute the lives of those suffering from it, researchers are still battling to find ways to reduce or eliminate its effects. And one recent study offers a certain degree of hope—and another example of how accidental discoveries can be beneficial to science.

Dr. Hubert Lim, a professor of biomedical engineering and otolaryngology at the University of Minnesota, was conducting experiments on deep-brain stimulation—"zapping" patients with electrodes in various contexts—when one experiment "went off course." Subjects of the experiment reported a reduction or disappearance of tinnitus symptoms as a result.

A randomized, multidisciplinary study based on Lim's experience subjected patients to electrical stimuli aimed at a particular subset of abnormally firing brain cells. In concrete terms, patients' tongues were fitted with a small set of electrodes that "zapped" the tongues at the same time as sequences of sounds were played in both ears. This therapy of "bimodal neuromodulation" was practiced for one hour daily over a 12-week period.

And the results were significant: 86 percent of subjects who went through with the treatment reported a reduction or disappearance of tinnitus symptoms. Moreover, these results persisted for a year following the therapy.

Another case of an unexpected reduction in noise amid the media-generated din of a pandemic.