Sex

Are Sex Differences in Mate Choice Really Universal?

A recent study compares men's and women's mate preferences across 45 countries.

Posted March 29, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Classic findings suggesting that men and women prefer different characteristics in a mate are now decades old.

- Investigators in 45 countries surveyed 14,399 people in an attempt to replicate earlier findings.

- Classic sex differences, especially an age difference between men and women, were found across societies.

- Some earlier findings about cultural variations were not replicated.

Do men and women really differ in what they want in a mate? If there are differences in the U.S. or other Western countries, are they reliable across time, and do they hold up across cultures?

Katy Walter and Dan Conroy-Beam are researchers at UC Santa Barbara who set out, along with over 100 other investigators (hailing from 45 different countries, from Algeria to Uganda, including Chile, Malaysia, Australia, Slovakia, and many points in between), to investigate the universality of sex differences in preferences for mates.

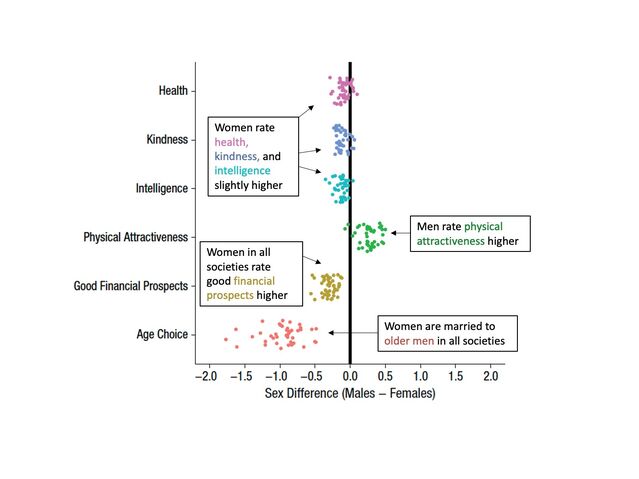

Classic findings in the area have suggested that:

a) A mate’s financial prospects matter more to women than to men.

b) A mate’s physical attractiveness matters more to men than to women.

c) Women are attracted to men who are slightly older than themselves.

d) Men desire partners who are relatively younger than themselves, but this desire for younger partners is small in young men, only becoming pronounced as men get older.

Walter and Conroy-Beam and their team also investigated a couple of more fine-grained details, related to particular evolutionary and social role theory predictions about cultural variations. Steve Gangestad, Martie Haselton, and David Buss had found that the preference for physical attractiveness was higher in countries with higher levels of infectious and parasitic diseases — a result that was explained as related to physical attractiveness indicating good health, and presumably, disease-resistant genes. In a separate line of research, Alice Eagly and Wendy Wood had found that some sex differences in mate choice were correlated with societal gender inequality. That finding was explained as supporting the idea that societies with more sex-linked division of labor placed more emphasis on men’s financial well-being, and women’s physical health.

The sample for the Walter et al. study was very large — 14,399 — which made it easy to detect any actual sex differences that existed, and to be confident that a lack of differences would be meaningful, and not just due to a lack of statistical power.

A few things stood out about the findings, reported in an article in Psychological Science. First, in every society Walter and colleagues examined, women placed more importance on financial prospects than did men (see the Figure). Second, men in most societies placed more emphasis on a woman's physical attractiveness, but this was not universal. The sex difference was close to zero in a couple of the societies, and very slightly reversed in a couple of others. Third, the biggest difference, one that held in all societies studied, was that women were married to older men (and conversely men were married to younger women). This difference varied according to participants' age, and was very small for people around 20 years old, but got substantially larger as people got older (in line with findings that Keefe and I collected from numerous societies three decades age, and which I discussed in the post "When statistics are seriously sexy").

In the new data set, Walter and colleagues did not replicate the finding that physical attractiveness was more desired in countries with higher levels of disease-carrying microbes and parasites. That might be because, since the time of the earlier studies, less developed countries have progressed greatly in health care, and vaccinations for formerly deadly diseases have become nearly universal (as discussed by Hans Rosling, see "10 biases that blind us to a world getting better").

Walter and colleagues did not find much support for the idea that sex differences in mate preferences are related to a country’s level of gender inequality. They did find that the age gap between men and their wives was greater in countries with greater inequality. This correlation may or may not inform us about causation — age gaps are lower in countries where women are less likely to age rapidly, due to lower birth rates and better health care, and women in those countries are also better educated, which means that they marry slightly later, rather than in their teens. Nevertheless, the general tendency for women and men to differ more over the lifespan held true across societies.

So, although there was not strong support for nuanced predictions about cross-cultural variations, there was very strong support for the existence of universal sex differences, suggesting that despite all the changes in the modern world, men and women still differ in what they prioritize in mates.

References

Gangestad, S. W., Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2006). Evolutionary foundations of cultural variation: Evoked cul-ture and mate preferences. Psychological Inquiry, 17, 75–95.

Kenrick, D. C., & Keefe, R. (1992). Age preferences in mates reflect sex differences in mating strategies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 15, 75–133. doi:10.1017/S0140525 X00067595

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions ver-sus social roles. American Psychologist, 54, 408–423. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.6.408.

Walter, K. V., Conroy-Beam, D., Buss, D. M., Asao, K., Sorokowska, A., Sorokowski, P., ... & Zupančič, M. (2020). Sex differences in mate preferences across 45 countries: A large-scale replication. Psychological Science, 31(4), 408-423.