Memory

Why We Stop Noticing the World Around Us

We often don't notice things unless we focus and are present.

Posted June 26, 2018

Despite having an amazingly complex brain, how much of our day do we spend on autopilot? For example, we don’t notice how often we check our phones, or say “Yea, totally, 100%” in conversation. We also start filling in the gaps when things don’t make sense to us.

Here are a few good demonstrations. Count the numbers of F’s in the following passage:

Finished Files Are the Result

Of Years of Scientific Study

Combined With the Experience

Of Years.

Most people count two or three (in the words Finished Files and scientiFic). But there are actually 6 F’s. Did you find all six? If so, you should be an editor. Probably my editor.

If you are still stumped, most people fail to count the Fs in the word OF (three times). It just doesn't register because we often don't think or process the word "OF" as a complex word, and the F sound in OF is pronounced more like a "V" sound (ov). Still, it is pretty amazing that we can't spot an F but humans can create wireless Internet!

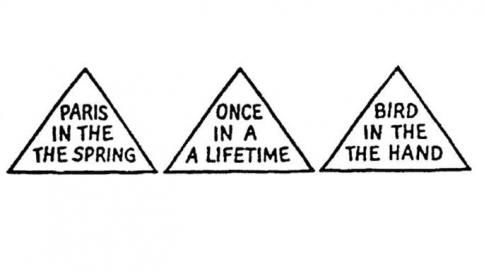

Now, read these sentences below out loud:

Did you notice notice anything anything odd about them? They all have repeated words, but often you don’t notice these words because it makes more sense to read “Paris in the Spring” and not “Paris in the THE THE Spring”. Still, you saw these repeated words (meaning your eyes went over them when reading) but didn’t notice them.

However, sometimes the clearest demonstrations are when we STOP noticing things, such as the buzz of the background traffic or hum of the refrigerator. We can tune out a lot. But when our attention is then drawn to this sound, we begin to notice again. Often we hear and see things that we don’t notice. How about a bright red fire extinguisher? Can you find it in the picture below?

You should be able to find two in plain view, one in the left part of the photo (that one should pop out quite quickly), and also one that appears smaller at the end of the hall. There also is one concealed (but labeled clearly in view) in a glass cabinet by the water fountain, as well as a red fire alarm on the wall. This part isn’t an illusion and is not trick (for Arrested Development fan-speak, there is an important distinction between an illusion and a trick).

Here is the harder part:

Now try to locate or remember where the nearest one is to you right now (at your office, in your home). In an office building like the one pictured above, we found that most people either don’t know or failed to notice (or didn't care) where one nearest to them was. It might be right down the hall, or right outside your door–you could have seen it thousands of times, but it doesn’t register. In our study, rather than telling people where it was, we asked them to find it, and they often failed.1 But here is the good news: First failing to find it, and then actually finding it (plus the experience of some embarrassment when you realized that you passed by it every day), lead to good memory for the location when people were tested again three months later. Failure can be a good learning event. It helps us realize what we don’t know.

A fire extinguisher could save your life, but we rarely need them, so we learn to tune them out. Failing to notice things can have its costs, and sometimes this can be an issue of life-and-death. Busy parents can actually forget a sleeping infant in a car, leading to what is known as Forgotten Baby Syndrome–such a tragic and sad thing that happens often enough that it has its own name.2

One near-universal law of psychology is habituation–we stop noticing things we see or hear many times. For example, we see logos every day, but people often can’t recall the details of the Apple logo (try the test in the references below if you don’t believe me).3 We often overlook things, usually because they don’t matter too much, and our mind helps us fill in the gaps. But there can be costs.

Sometimes we only know how our mind works by noticing when it fails, so don’t be afraid to test yourself. I learn so much about my mind when it fails me, as that is when I begin to appreciate how it works so well most of the time. These demonstrations are not meant to make you feel stupid (though it can be a nice way to illustrate it!). Testing yourself and failing can be a very potent form of learning, as we can learn what we know but sometimes more importantly, what we don’t know. By being present, patient, and observant, and not fear a little failure when the stakes are low, we can notice more about the world around us.

References

References

[1] Castel, A. D., Vendetti, M., & Holyoak, K. J. (2012). "Fire drill: Inattentional blindness and amnesia for the location of fire extinguishers." Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74, 1391-1396.

[2] Blake, A. B., Nazarian, M., & Castel, A. D. (2015). "The Apple of the mind's eye: Everyday attention, metamemory, and reconstructive memory for the Apple logo." The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68, 858-865. For an online demonstration, look here.

[3] Diamond, D. (2016). "Hot Car Deaths: How Can Parents Forget a Child in a Car?" CNN Health.