Creativity

One Simple Trick to Think Outside the Box

Yes, your creativity can be enhanced.

Updated November 20, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Research shows that creative problem-solving is possible for those who aren't natural out-of-the-box thinkers.

- Cognitive psychologists have uncovered over a dozen techniques to enhance creativity in "normal" thinkers.

- Defining what is not true about a problem to be solved can bring powerful benefits.

The air war over occupied Europe and Germany during WWII was taking a heavy toll on Allied bombers as well-trained and equipped German anti-aircraft crews shot down one bomber after another.

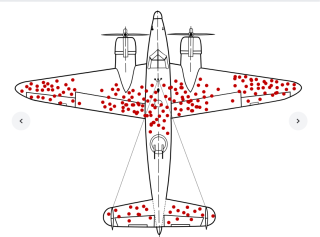

Wanting to increase the survivability of their bombers, Allied air powers analyzed the pattern of damage to aircraft in order to up-armor the most frequently damaged regions. This effort produced a composite “scatter plot” of damage like the one in this diagram.

While the engineers were figuring out how to add armor in the most frequently hit locations, someone on the team suggested that they rethink the approach, pointing out that the scatterplot showed where aircraft could take a hit and still survive, because the plots were taken only planes that had successfully returned to base. Hearing this, the team took a second look at the scatterplot, factoring in knowledge of how the aircraft worked (e.g. it couldn’t fly without engines or a cockpit) and concluded they were about to armor exactly the wrong places. They actually needed to reinforce the blank regions of the scatterplot, because only planes that avoided damage in those vital areas survived.

The team member who redirected the effort was a classic example of an out-of-the-box thinker, the “box” in this instance being an instinctive focus on damage vs. non-damage.

The Problem of In-the-Box Thinking

Like most of the team members in the story, we are often confined to certain mental “boxes,” based on our innate cognitive biases, experience (if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it), incentive systems (bureaucracies and social pressure discourage divergent thinking), or personalities (some people are less open-minded than others).

But the problem is, although we’ve all heard of “thinking outside the box” very few of us actually know what our own “box” is. Unlike the damaged airplane example, where the “box” is sharply defined by the boundary between damage and non-damage, the problem space most of us face is murky and ambiguous, where there are no obvious dividing lines for us to cross to escape our “box.”

Turning award-winning computer scientist Alan Kay described this problem aptly when he observed “I don’t know who discovered water, but it wasn’t a fish.” Put another way, we are usually blind to our own cognitive blindspots and biases because it’s very hard to see ourselves from an outside perspective (like a fish out of water watching fellow fish in the water for the first time).

Researchers who study creativity, problem-solving, and innovation, such as Raymond Nickerson (1) and Jennifer Haase (2), assert that you don’t have to be born a Picasso or Einstein to overcome such cognitive limitations. Rather, you can enhance your creativity in a dozen different ways—including making a list of how to use ordinary objects, such as bricks, in unorthodox ways (3), composing diverse teams, rewarding curiosity, and encouraging risk-taking (2).

And all of these varied techniques are worth investigating if you want to “think outside the box” more than you do now.

But working over 20 years at Disney Imagineering, where I participated in innumerable brainstorming sessions with highly creative Imagineers seeking to become even more creative, left me with the belief that one creativity-boosting technique in particular stands head and shoulders above the others for simplicity and effectiveness: Thinking out of the box by first sharply defining the boundaries of that box, so that you know where to cross them.

Visualizing the Box in Order to Leave It

Let’s return to the fish-in-the-water analogy and imagine that you are that fish. Unless you happen to be a flying fish or a semi-amphibious snakehead, all you’ve ever seen is water, so it would never occur to you that an environment exists that is non-water.

Then someone—maybe a flying fish or snakehead—challenges you to imagine a world where no water surrounds you. Your first question—if Alan Kay is right—is, “What's water?” At which point your interlocutor responds not with an answer, because you wouldn’t understand it, but with a question: “What if you were in a place where nothing went into your gills when you 'breathed' in and nothing kept you from sinking to the bottom, and there was nothing to push against when you moved your body and fins to swim?"

Hearing, for the first time, a definition of “non-water,” you have gained two valuable insights: what water is and, more importantly, from the point of view of thinking outside the box, what it is not.

So now, be the fish and challenge yourself with questions about your personal or professional life. In particular, questions such as “What do I believe is not true about the problem I am trying to solve or opportunity I am trying to seize?"

Here’s an example of using the “not true about my situation” trick to define and escape a mental box.

In 2016, when I was designing the optics for Disney’s Jedi Challenge Augmented Reality display, which turned user smartphones into “holographic” projectors, too much light was escaping from smartphone screens to make the system viable. So, after months of struggling, I paused, and asked “What is not true about light from smartphone screens?”

By randomly playing around with different types of phones, I discovered that what was not true about all smartphones was that the light from the screens was “normal” light. Rather, all brands of phones had some kind of polarization (like polarized sunglasses). That insight allowed me to use special filters to recapture enough escaping light from the phone screens to make the whole project feasible.

Out-of-the-box thinker Steve Jobs provides an even more powerful example of “not true” thinking when he strove to grow Apple’s computer business over 20 years ago by imagining new sales coming from devices that were not perceived as computers (but really were) such as iPods, iPhones, and iPads.

By defining the parameters of what your particular problem or opportunity is not, like our proverbial fish, you will gain fresh insights about what your problem is, along with novel ideas—such as Apple’s spectacular move into mobile devices—about how to tackle it.

The bottom line is that we all carry around a "box" in our heads that confines our thinking, and I believe the most important first step to escaping that box is to admit, 12-step style, that it’s there and to define its boundaries so you know where to step over them.

So, be that fish, define your boundaries so that you can cross them.

Being a fish out of water may be scary, but hey, our distant ancestors did it, or we wouldn’t be here. And the end result—humans that can imagine new ways to create—turned out to be a spectacular out-of-the-box idea.

References

1 ) Nickerson, R.S. (1999). "Enhancing creativity". In Sternberg, R.J. (ed.). Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press.

2) Haase, Jennifer; Hanel, Paul H. P.; Gronau, Norbert (27 March 2023). "Creativity enhancement methods for adults: A meta-analysis". Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. doi:10.1037/aca0000557. S2CID 257794219.

3) https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-020-01802-y