Genetics

If You Were Wrong About a Core Belief, Would You Admit It?

A single white mother and her adopted biracial son tell their unexpected story.

Posted April 28, 2020

Suppose you had a core belief that you had assumed to be true and defended all of your adult life – and then you came to realize you were wrong? And suppose further that your belief had implications not just intellectually, for your belief system, but for enormously consequential decisions you made that affected your life and a child’s life?

As a single woman considering adoption in the late 1970s, E. Kay Trimberger’s core belief was that “nurture was everything.” It was a widely embraced belief at the time.

“When one applied this theory of the primacy of nurture to adoption,” Trimberger explained, “one healthy baby was as good as another; what mattered was how the baby was raised ... My son, whatever his race, would share my white, middle-class values, with their emphasis on the importance of education and work to the good life.”

That’s not how it turned out.

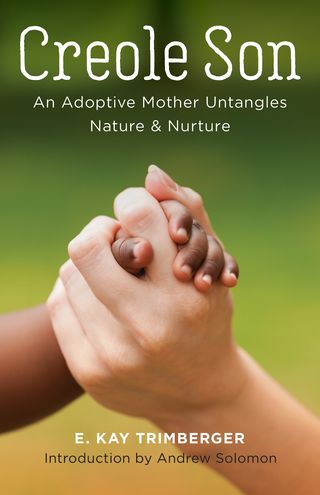

Trimberger tells the story in her new book, Creole Son: An Adoptive Mother Untangles Nature & Nurture. I’ll admit, I only read it because Kay wrote it and because it is about her experiences as a single mother. I have no particular interest in adoption. But I loved this book.

I first got to know Kay Trimberger as a fellow scholar, when I read her important 2005 book, The New Single Woman, a thoughtful and affirming 9-year study of single women that defied all the prevailing stereotypes. We got to know each other over time and wrote several articles together. For example, with UCLA law professor Rachel Moran, we urged our fellow scholars to “Make room for singles in teaching and research,” published in 2007 in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Kay has her own blog here at Psychology Today, Adoption Diaries. She has also contributed guest posts to this Living Single blog, starting back in 2008, when this blog was launched.

Creole Son: A Quick Overview

Trimberger adopted Marco, a biracial baby boy whose birth parents were from Louisiana, and raised him in Berkeley. Marco’s childhood was mostly happy. Mother and son seemed to bond easily and shared many experiences that both still remember fondly. But adolescence was trying, and adulthood even more so, as Marco struggled with addiction.

Over time, Marco’s life seemed to diverge even more markedly from his mother’s. Trimberger is a sociologist. To try to understand Marco’s experiences, and the experiences of other adopted children, she delved into the very challenging behavioral genetics studies of adoptive families. There, she learned that nature plays an indisputable role in the life experiences of adopted children – in many ways, a more significant role than nurture. In fact, one of the most significant findings from behavioral genetics, Trimberger noted, was that “differences between parents and their adopted children increase over time.”

Marco was interested in meeting his birth parents, and when he was 26, his mother helped make that happen. She also traveled to Louisiana to meet his parents and extended family, sharing meals with them in their homes and going to religious services and other events. Her impressions were consistent with what she had learned from the behavioral genetics research; Marco shared some striking similarities with the members of his family of birth.

A Few of the Things I Loved Most

#1 The story is riveting. The brilliant scholar, Kay Trimberger, is so hopeful about her biracial boy born near the bayou and what she could offer by raising him in mostly white, progressive Berkeley, California. By her own admission, her expectations were painfully naïve. How did her sweet, joyful, extraverted boy become a drug-addicted adult, employed in unconventional ways if at all, who spent time in jail and even on the streets? It is shocking and heartbreaking, told unsparingly and without melodrama.

#2 Kay’s experiences with Marco’s birth family, so different from Kay culturally and in many other ways, were equally fascinating. I loved the evocative descriptions of the people and the places. I appreciated the insights Kay gleaned from those visits and from the ties she continued to maintain with some of the relatives for years afterward.

#3 I learned so much from Creole Son. Kay beautifully interweaves her own story and Marco’s with the findings from behavioral genetics studies of adoptive families, explained ever so clearly.

#4 Even the Appendix was a treat. For example, it includes an eye-opening section, “Our changing understanding of adoption,” where I learned that in the U.S. before the 1920s, “Single women, especially unmarried professional women, were encouraged to adopt children, but by 1945 this was no longer permitted.”

Kay explained that in the 1940s, open adoption practices were replaced by strict closed adoptions; often, new birth certificates were created, listing only the names of the adoptive parents. “This attempt to make an adopted family identical to a biological one,” Kay observed, “coincided with the decline of extended family ties and the idealization of the nuclear family.”

#5 Andrew Solomon, award-winning author of the bestseller, Far from the Tree, wrote a terrific introduction.

#6 Marco told his own story in a very touching afterword. Here are a few snippets:

- “For me, being adopted and growing up mixed-race with a white mother in a single-parent household never seemed strange or unusual…”

- “Being adopted gave me an edge, a little more character, so I was not just like everyone else.”

- The one time he experienced a problem: “I was involved in an altercation with a kid who made fun of me for not having a real mom. It didn’t make sense to me, because my adopted mother was then the only mom I knew.”

- “When, in the later years of high school, drugs like weed, cocaine, ecstasy, and meth became part of the arsenal to feed my addiction, it was not about racial identity, because few black kids I knew tried any of them. It was affluent white kids who were drug users and sellers.”

- About the reunion Kay arranged with his birth family: “Even though my mom had arranged for the reunion, I didn’t want her to think for a moment that someone could take her place. I was scared it would hurt her if I connected with my biological mother.”

You can read more about Creole Son at Kay Trimberger’s website.