Leadership

The Psychology of Design: Leadership and Transition Dynamics

Part 4: Understanding group dynamics can help to facilitate system design work.

Posted August 20, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Leaders have a perspective on the problem their group is facing and the team they are working with.

- Group facilitators work closely with leaders, but they stand outside of the group content and work to facilitate group intelligence.

- Facilitators must be resilient and adaptable and work to uphold freedom as non-domination for the purpose of maximizing group intelligence.

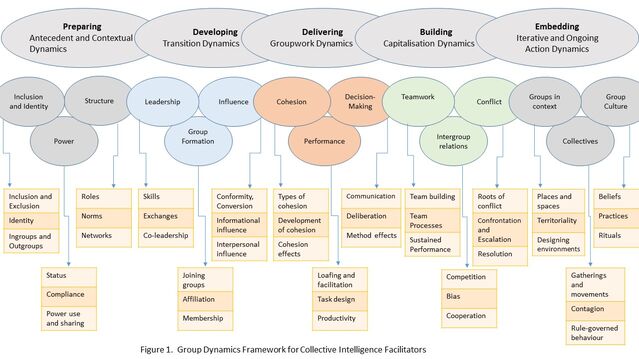

Welcome back to our fourth blog post in this series focused on group dynamics and system design. Central to our blog series is a simple idea: We need to understand group dynamics if our goal is to facilitate groups engaged in system design work. Our framework can be seen in Figure 1 (below). In this blog post, we will focus on transition dynamics.

The transition

As a group facilitator working with multiple groups across a variety of different projects, you need to get comfortable with transitions.

Imagine a three-year project where you’re working with stakeholders and experts to develop an open data platform that allows citizens and public administrators to make good use of open data while addressing a variety of different national and local problems. Your goal is to facilitate the group as they engage in system design work. A team needs to come together to understand the design challenge they face and develop specific requirements for an optimal system design.

Transition dynamics unfold from a point in time when you have developed an initial understanding of the design challenge to a point in time when you will meet with a group to facilitate their system design work. During this transition, the facilitator is focused on (1) Leadership, (2) Group Formation, and (3) Influence dynamics.

Leadership

Leadership is always important. As mentioned in Part 3, when working with groups, we often use a collaborative system design method developed by John Warfield. In his classic work, Warfield (1976) proposed three functions and 12 elements (including leadership) that need to be coordinated in system design work:

- The enabling function, says Warfield, is critical for establishing (1) the team that will use a specific (2) methodology to address a societal problem. This enabling function involves (3) a sponsor who controls (4) funds and who has sufficient interest in (5) the ideas related to a specific (6) societal issue.

- The implementing function involves coordination between (7) the stakeholders in the societal issue and (8) the doers who decide to act and carry out the proposed actions based on (9) the results of the system design work.

- Finally, the managing function involves (10) leadership in identifying issues to focus on and (11) planning and designing a scenario for the future, where ultimately, “Through (12) brokerage among the sovereign entities involved, including the sponsor, the team, the stakeholders, and the doers, plans that incorporate the results of exploration of the issues are translated into results in society” (1976: p. 34).

Group facilitators work closely with leaders. Leaders will have a perspective on the problem the group is facing and a unique understanding of the team they are working with. However, they generally don’t understand systems thinking and design methodologies.

The group facilitator will often serve as a teacher/educator in explaining to sponsors/brokers/leaders what can be done and how much time will be required for system design work. As the group dynamics needed to optimize productive systems design work may clash with the normal project management approach adopted by leaders, a natural tension between group facilitators and group leaders can arise. Indeed, central to a productive working relationship with leaders is the cultivation of a natural, cooperative, and open, reflective tension in relation to group process facilitation.

Understanding the behavior of leaders is critical. This includes the relationship that leaders have with their group, their specific leadership style and skill, leader-follower exchanges, co-leadership dynamics, and the vision and goals the leader communicates in leading their group. In the transition to working with a design team, group facilitators need to meet with leaders for brokerage work. Here, they will (1) reflect on the issue the group seeks to address, (2) clarify system design objectives, and (3) discuss different systems thinking and design methods. Group facilitators will describe the procedural details of each method in turn, and it will take time for leaders to understand the methods.

On the face of it, group facilitators have certain things in common with group leaders: for example, a shared focus on project and team facilitation. But the group facilitator is not a group leader. Facilitators stand outside of the content the group is focused on; they focus instead on the group process and the implementation of system design methodologies.

While leaders might naturally be interested in the behavior of facilitators, once methodologies are agreed on, and a plan is in place, the leader’s focus is oriented to the systems thinking process. Conversely, the group facilitator pays close attention to the behavior of the leader, along with other members of the group, as they seek to manage the implementation of the process.

During early brokerage and planning meetings and throughout the project, facilitators maintain a curious, reflective, and neutral stance in relation to all aspects of group work. If the leader's influence is too dominant to proceed with productive group work, the facilitator will provide feedback on the conditions that need to be in place to maximize group intelligence and collaborative systems thinking and design work.

A sense of hopefulness runs throughout all stages of group work. For example, a group dealing with difficult issues will sometimes become discouraged, and a facilitator’s understanding of what can be accomplished through continued group work becomes critical. This hopefulness needs to be coupled with resilience, and when a facilitator demonstrates resilience in the face of adversity, this can help a group through difficulties. It can also support leaders who can struggle to maintain resilience in the face of challenges their team is facing.

When a leader commits to the application of systems thinking methodologies, in principle, they are agreeing to empower collective intelligence and pass over a degree of influence to a design team. Facilitators must operate with mindfulness and resilience and adaptability throughout and work to uphold freedom as non-domination for the purpose of maximizing group intelligence. Fundamentally, the facilitator is oriented to the issue, the team, their methods, and their group process. The facilitator recognizes the leader as one member of the group—an influential member in the overall group and project dynamics.

Transition dynamics include not only a focus on (1) leadership dynamics but also (2) group formation and (3) influence dynamics. The formation of groups for the purpose of system design thinking is somewhat unique. Facilitators need to understand group formation dynamics: joining, affiliation, attraction, and membership dynamics. Influence dynamics extend beyond the influence of the leader to the set of influences across the whole group. We’ll talk about these influences in more detail in coming blog posts.

References

Hogan, M.J., Harney, O., Moroney, M., Hanlon, M., Khoo, S.-M., Hall, T., Pilch, M., Pereira, B., Van Lente, E., Hogan, V., O’Reilly, J., Groarke, J., Razzante, R., Durand, H., Broome, B. (2020). A group dynamics framework for 21st century collective intelligence facilitators. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. doi:10.1002/sres.2688

Warfield, J. N. (1976). Societal systems: Planning, policy, and complexity. New York: Wiley.