Psychology

The Psychology of Design: Enter the Dynamics

Part III: Antecedent and contextual dynamics.

Posted May 25, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

For those of us who were teenagers in the 1980s, the teen comedy, Ferris Bueller's Day Off, was a classic movie for many reasons. As teenagers, we could relate to the stifling school environment that Ferris Bueller sought to escape from, and we all wanted a day off—anyone, anyone? Ferris worked hard and he worked smart to engineer a great day off from school. We admired his relaxed approach to adventure, his skilled use of gadgets and computers, and his ability to get along with everyone. Ferris also offered us his simple version of mindfulness, illustrated in the opening and closing lines of the movie:

“I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. Life moves pretty fast. You don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

My kids certainly appreciated the sentiment when we watched the movie recently.

Indeed, life moves even faster these days. Information outputs and exchanges have accelerated. The number of apps and gadgets and ‘systems’ we use to manage information complexity and life challenges is mind-boggling. Mark Zuckerberg’s philosophy of “move fast and break things” seems strange to those of us who grew up in households where our mother reminded us regularly ‘not to break things.' And the manic pace of ‘disruptive technology’ design seems, well, a little disruptive— and certainly a world away from Ferris Bueller's relaxed approach to life design.

Well, in this blog series, we’ve said it before and we’ll say it again, system design work isn’t easy. It’s not easy because system design work requires systems thinking, and systems thinking takes time. Some people say that the era of “move fast and break things” is over. Thank God, I hear my grandmother say. But is it really over, really? We need to stop and look around. In reality, it’s not easy to slow down and design better systems when everyone is running around distractedly looking for ‘new ways to be disruptive.' The drive to “move fast and innovate” is everpresent, even if you think you’re not breaking things.

Perhaps what we really need is more speed and less haste. Perhaps, as we make the move from ‘breaking things’ to working cooperatively to design quality systems, we can keep in mind the words of Mitsuyo Maeda: “Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.” A quality system design process might seem slow, but it’s much faster than one hasty mess after another. A critical mass of people needs to slow down together for the era of “move fast and break things” to be truly over. This involves culture change, and culture change takes time.

As we mentioned in the previous blog post, the (slow) learning and application of systems thinking design methods can help groups. And group facilitators can help groups. Facilitators can help design teams with the application of systems thinking methods and the group dynamics involved in the application of these methods.

Good, we can debate this further, but slowing down is often a good start. It allows groups to experience something akin to the ‘extended now’ moment Eckhart Tolle talks about. Now, at least, the design group can begin to embrace the reality that societal systems are complex, there are many elements that need to be considered. This seems obvious when we think about it—particularly when we embrace the systems thinking process—but, still, people are reluctant to slow down and put aside the time needed for systems thinking design work.

We’ve mentioned the excellent book by Michael Jackson, Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity, and all the systems thinking methods a group might use to get a handle on technical complexity (e.g., Operations Research, Systems Engineering), process complexity (e.g., the Vanguard Method), structural complexity (e.g., System Dynamics), organisational complexity (e.g., Organisational Cybernetics and the Viable Systems Model), people complexity (e.g., Strategic Assumption Surfacing and Testing, Interactive Planning, Soft Systems Methodology), and coercive complexity (e.g., Team Syntegrity, and Critical Systems Heuristics).

Another method we can add to this list is Interactive Management (IM), an applied systems thinking method developed by John Warfield. We have used Warfield’s method in a number of projects, including technology design projects. We’ve also combined IM with scenario-based design methods, and, as mentioned, we recognise that methods are not ‘separate’ from one another, they can be usefully combined. We recognise that group facilitators need to continue learning new methods and help design teams think through an optimal synthesis of methods to support project work.

There’s great joy in trying out new methods. Of course, this joy manifests—even if only for brief moments—in the context of complex group dynamics. Let’s enter this complex space now.

Enter the Group, Enter the Dynamics

Given the quality of communication and collaborative action required, the application of systems thinking design methods often involves working with small groups (e.g., 5 – 20 people). However, methods can scale to larger groups (e.g., organisations, communities) and the influence of systems thinking design projects can scale to global level impacts. Regardless of what you think of their products, it’s worth noting that the “move fast and break things” community are often, at their core, comprised of relatively small design teams, but when they push their designs out into the world, the global impact of the designs—as my granny might say—‘can be a little disruptive.'

Regardless of the system design methodology selected, it’s important to note that groups will have varying levels of past experience working together and regardless of the size of the group working together, their {small group dynamics} are always embedded in {larger group dynamics} that influence their functioning and societal impact.

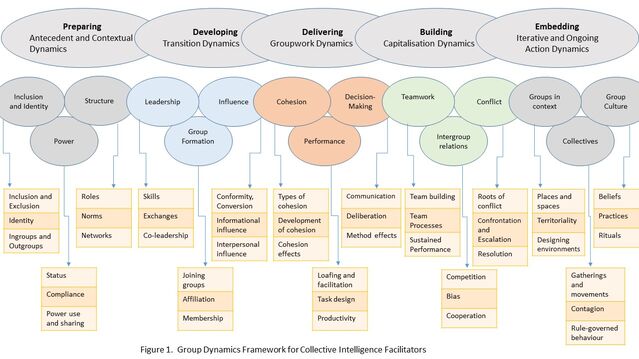

From a group facilitation perspective, given the process focus of systems thinking and design work, we make a distinction in our paper between {proximal} and {distal} group dynamics, that is, dynamics that play out in the proximal interactions between group members during the systems thinking group-work phase (located in a central position in Figure 1), and the broader antecedent, contextual, transition and post-session group dynamics within which systems thinking group-work interactions occur.

As we move to talk about group dynamics, I want to make something clear: Michael Jackson’s book, Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity, is a brilliant book. But you may notice an interesting gap as you read, the book says less about how to facilitate groups in the use of systems thinking design methods. Yes, I hear you, this is the type of ‘interesting gap’ that perhaps only a group facilitator would notice. While often ignored, the role of the group facilitator is important. Now this varies across approaches, but the application of systems thinking methods in a group design project generally involves working with a facilitator, and sometimes, a facilitation team. The facilitator(s) work closely with the expert and stakeholder group, helping them apply methods in a way that is fit for purpose. From our perspective as group facilitators following Warfield’s method— and we are strict in this regard—the facilitation team focuses exclusively on method and process, and thus we adopt a curious, reflective, and neutral position in relation to systems thinking content. The ‘content’ of system design work is exclusively the product of the stakeholder and expert group.

While most of the skilled engagement of the facilitation team centres on supporting groups in the application of systems thinking methods, facilitators also need to understand, monitor, and manage the proximal group-work dynamics that play out within the group during the application of the method. And facilitators need to understand, monitor, and manage more distal group dynamics. This includes the antecedent, contextual dynamics that influence how systems thinking sessions are brokered and organised in advance of group-work. It includes the transition dynamics that influence the coming together of a group and their initial productive functioning. And it also includes the post-session group dynamics that influence the ongoing systems thinking and design process and outcomes.

We’re going to talk about all these different phases of work as we move forward here. The main reason for this wide lens of analysis and engagement—where we focus on distal group dynamics in addition to proximal group dynamics—is because, very often, facilitation teams are embedded as part of a project for an extended period of time. As such, the facilitation team needs to maintain a focus on group facilitation in a principled and informed manner and in a way that serves the productive and successful workings of the group. Overall, this implies understanding distinct but overlapping aspects of group dynamics during different phases of working with a group. While these phases can vary depending on the method used, systems thinking project work tends to have a duration that extends from months to years, and even decades in some cases (Broome, 2006).

Our group dynamics framework is presented in Figure 1. The relevant scientific literature for educational programme designers can be accessed across a variety of textbooks (e.g., Forsyth, 2014, 2018; Levi & Askay, 2020). I’ll include a few hyperlinks in the flow going forward, but they are largely for illustrative purposes and to give you a sense of where analysis and exploration can take you in your group dynamics adventures. My advice is to begin by reading the textbooks, they’re ideal for reflective thinking and as a prompt for context-specific analysis work.

Antecedent and Contextual Dynamics

Let’s begin by noting a few key considerations in relation to Antecedent and Contextual Dynamics, located to the left of Figure 1. The key aspects of group dynamics we focus on here relate to

- Inclusion and Identity

- Power

- Structure

It should be noted that we are doing two things as we work. First, we are analysing the existing empirical group dynamics literature to understand the types of dynamics that have been observed across different study contexts. Second, we are analysing our local problem situation in an effort to understand group dynamics that are operative, while also working to anticipate and plan for the different group dynamics that may play out when groups come together to engage in collaborative project work.

In simple terms, in advance of inviting a group to engage in a systems thinking design session, we need to do our homework and engage in some advance planning. A curious, reflective, and neutral stance in relation to all aspects of engagement, analysis, planning, and simulation of group-work is sustained throughout, in advance of working with a group, while working with a group, and in follow-up work with a group. To begin with, we need to understand Inclusion and Identity dynamics. This often begins with a process of mapping the stakeholder and expert ecosystem. This is essential if you want to design a process that is truly collaborative and cooperative, including and engaging key stakeholders and experts. In this context, the group facilitator needs to understand the effects of inclusion and exclusion on group behaviour, the influence of group identity on behaviour, and inter-group interdependencies including in-group and out-group dynamics. Key questions you might ask here include:

- Have you a clear understanding of the stakeholders and stakeholder groupings for whom the problem you are addressing is directly relevant?

- Do you have an understanding of the key expert groups and domains of knowledge and skill that are relevant to address the problem?

- Do you have an understanding of how different group identities influence the perception of the problem situation?

- Do you have an understanding of how people with different group identities perceive one another and behave in relation to one another?

- Do you have knowledge of the history of inclusion and exclusion of different stakeholder and expert groupings in the context of past efforts to address the problem, and the impact of inclusion/exclusion dynamics on current experience and behaviour within and across groups?

- Can you perceive and anticipate inter-group interdependencies that are important for modelling both the current state of the system and future transformations of the system?

Also critical for brokerage and planning of systems thinking group-work is an understanding of Power dynamics, including the group dynamics linked to status, compliance, and power use and sharing within and between stakeholder and expert groups. While systems thinking facilitators need to manage and monitor equality of input and influence during group-work, they also need to understand how power dynamics influence group activity and productivity throughout the whole lifecycle of a project. Key questions here include:

- How are status and power differences between group members likely to influence their communication and collaborative engagement during a systems thinking session, and during follow-up system design implementation work?

- Do you have an understanding of compliance histories between groups and members, and can you simulate how past and present dynamics will influence future power use and power-sharing dynamics that are proposed as part of system change?

Importantly, a comprehensive understanding of inclusion, identity, and power dynamics cannot be achieved without an understanding of group Structure, including the roles, norms, and network structure of groups. Immersion in the working context of groups is needed to understand the specific dynamics at play. Members of the facilitation team will often use the word ‘immersion’ in this context, as it highlights both the depth of reflective engagement, and time, needed to develop an understanding of groups and their organisations in advance of bringing stakeholders and experts together.

Systems design project work is often initiated on the assumption that partnerships across stakeholders, experts, and implementation teams will be established. From a naïve point of view, they might be assumed to be ‘a given’—but these partnerships play out across multiple group structures and organisations, which often operate with different norms, across a diverse role landscape, and with a collection of stronger and weaker network ties within and across groups and organisations. Understanding the overall structure of groups across this landscape is important for effective group facilitation.

None of this is easy, and indeed, it’s only the beginning. In the next post, we will consider the transition dynamics, as we seek to facilitate groups to work productively together, assuming we can get them to the design room in the first instance.