Teamwork

Teamwork and Societal Problem Solving

The challenge of integrating content expertise and methodological expertise

Posted July 3, 2019

'Teamwork makes the dream work!' So the saying goes, and somehow we intuit the underlying wisdom. But how do we support teams to collaborate effectively? And how do we do this when team members have diverse knowledge and skills that need to be coordinated for effective collective action?

Amidst the globalized banter of modern society, one could form the impression that wisdom is going out of fashion. Drawing upon the Latin form sapiens in 1758, it’s unclear if Linnaeus viewed the ‘wisdom’ of Homo sapiens as derived from their capacity for communication and cooperation. An ideal of the enlightenment era, and one we still hold dear, is that we can communicate our way to wisdom, and cooperation will follow suit. Global communication and information flows have certainly increased since 1758, and cooperation dynamics have grown in complexity, but the wisdom of the crowd is often drowned out by the noise of the larger crowd. In a previous blog post, we noted that dynamic choices are most accurate in small groups and thus the wisdom of a large crowd might best derive from the iterative, distributed work of a team-of-teams, with the larger ‘crowd’ working across multiple sub-teams.

However, this is largely an ideal, an elaboration of the enlightenment ideal, which is difficult to engineer in practice. Indeed, cooperation in modern societies is increasingly challenging as groups grapple to synthesize increasingly diverse knowledge and skills in efforts to resolve shared problems. In academic speak, although teamwork is increasingly valued (Forsyth, 2014), multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary teamwork is difficult. Major national and international research funding agencies are investing in multi-disciplinary research designed to achieve societal impact, but these teams often struggle to communicate with one another and identify practical teamwork methods (Warfield, 1976, 2006). In the broader world of innovation, the new ideal of ‘quadruple helix’ cooperation that transcends traditional silos between government, industry, academia, and civil participants is increasingly prominent. But again, beyond the ideal, the reality of this work is challenging.

Case study analyses reveal the difficulty of establishing cooperative dynamics in groups, particularly when group members lack established cooperative norms, have no means of monitoring each other, no effective sanctions to prevent non-cooperation, and no methods to support consensus-building (Ostrom, 1990). Other teamwork challenges include poor planning in advance of group work, organizational culture barriers, and group composition and cultural diversity barriers (Broome and Fulbright, 1995).

Consistent with the collective intelligence and applied systems science approach advocated by John Warfield (1976; 2006), we believe it’s valuable to understand the challenges associated with cooperation when facilitating teams that are working to address complex societal problems. As collective intelligence facilitators, we often make use of Warfield’s method, Interactive Management (IM), to support teams in developing structural models describing interdependencies between problems they are working to address. Central to Warfield’s collective intelligence method is a software facilitated process that embeds the logic of group members, represented in a matrix of decisions, in the form of a graph or systems model. Members of our Collective Intelligence Network Support Unit (CINSU) have used Warfield’s method to support teams across a variety of contexts, including mediating peacebuilding in protracted conflicts (Broome, 2006; 2017), improving tribal governance process in Native American communities (Broome, 1995a, 1995b), developing a national wellbeing measurement framework (Hogan et al., 2015), and mobilising communities across Europe in response to marine sustainability challenges (Domegan et al., 2016).

Recently, CINSU members published a paper focused more directly on cooperation dynamics. Specifically, we sought to understand the typical challenges that teams face as they work to integrate content expertise and methodological expertise when addressing complex societal problems. CINSU members identified a broad range of challenges (see Table 1), voted to select the most critical challenges, and then examined relations between these critical challenges in a systems model (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Challenges teams face integrating content expertise and methodological expertise

Stakeholders

Failure to correctly identify and include all of the key stakeholders

Lack of buy in from stakeholders

Failure to ensure that all stakeholders have a minimal common core of knowledge or understanding

Group dynamics

Unequally empowered stakeholders

Unwillingness to share due to protection of domain expertise

Inability to appreciate and respect different expertise as being equally valid

Planning

Failure to systematically plan and prepare for the integration of content and methodological expertise

Failure to specify adequate delivery timelines

Lack of contingency planning

Resources

Lack of funding, time, or other supporting resources

Refusal to recognize resources of team members (i.e., a deficit mentality)

Tensions due to time investment of various stakeholders e.g. short-term academic goals, agencies, clients

Defining goals

Failure to clearly state or agree the goal or problem

Unwillingness to image alternative futures

Failures in prioritization of critical issues by experts

Engagement

Inherent inertia in the system which militates against change or innovation

Lack of active engagement

Lack of accountability

Communication Issues

Lack of openness and ability to listen with curiosity

The challenge for the facilitator to be able to recognize and communicate stakeholders voices in the process

Inability to translate ideas into ‘languages’ understood by a diversity of stakeholders

Resistance and fears

Failure or inability to question

Resistance to learning or to taking in new information

The impact of previous negative experiences on initiative and willingness to change

Collaborative Methodology

Resistance to methods and content which are seen as being less valid, reliable, or prestigious

The demand for a ‘solutionist’ approach distorts and dominates integration and collaboration processes

Shortage of platforms, methods, and procedures enabling different views to be heard

Epistemic Heterogeneity

Conflict between ideological assumptions – paradigmatic (nature of the issue) and prescriptive (what is to be done) levels amongst stakeholders

Excessive specialization (shortage of holistic perspective)

Conflict between broad methodological worldviews e.g. positivist vs critical

Collective Intelligence Group Systems Model

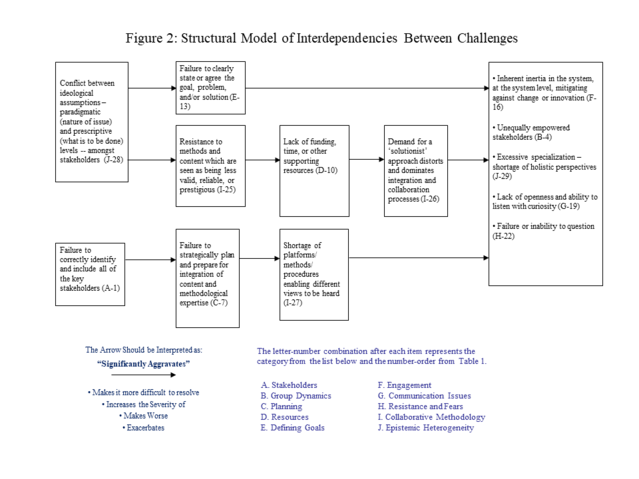

The systems model describing interdependencies between selected challenges is to be read from left to right, with arrows connecting challenges indicating ‘significantly aggravates’. There are two primary paths of influence in the model.

First, the challenge to the left: conflict between ideological assumptions amongst stakeholders for both paradigmatic and prescriptive issues significantly aggravates other challenges, including failure to clearly state or agree the goal the team is addressing, and resistance to methods and content seen as being less valid/reliable/prestigious.

Resistance in turn has negative effects on the allocation of resources for cooperative teamwork and demand for a ‘solutionist’ approach which distorts and dominates integration and collaboration processes. These challenges aggravate a host of interdependent problems to the far right of the systems model, included inertia, lack of openness, failure to question, excessive specialization, and unequally empowered stakeholders.

The second path from the far left of the structure begins with failure to correctly identify and include all of the key stakeholders, which significantly aggravates Failure to systematically plan and prepare for integration of content and methodological expertise, which in turn significantly aggravate Shortage of platforms, methods, and procedures enabling different views to be heard. Again, these challenges collectively drive a host of other problems to the far right of the structure.

Reflections

The deliberations and systems thinking of the CINSU team reinforce a number of key ideas that are widely understood: First, although there is limited consensus across academic disciplines as regards how best to achieve it, inclusive participatory planning processes are seen as increasingly important when addressing complex societal problems (Leyden et al., 2017; Reed et al., 2017).

Warfield recognized this better than anyone else in his classic 1976 book, Societal Systems. Indeed, when it comes to integrating content expertise and methodological expertise in a team-based setting in efforts to design and implement solutions for complex social issues, the most critical challenge identified by the CINSU team during voting relates to the need to identify and include all key stakeholders.

While it is often ignored in practice, it is clear that if stakeholders are not included, relevant perspectives and skills cannot be shared and synthesized by the team. Related challenges include unequally empowered stakeholders, a classic challenge in organizational teamwork and democratic designs (Forsyth, 2014; Mulgan, 2018). Unequal power across stakeholders can cause tension, conflict, and disengagement – and it violates a basic principle that when working together democratically people should be free from domination in their relationships with one another (Pettit, 2014).

Another cluster of challenges relates to planning, resources, and defining goals. It’s a common problem, but without proper planning, teams often waste their time and resources. Conversely, with effective planning, good things can be achieved, for example: steps can be taken to integrate group work in the context of the organization's culture, group composition can be better determined, and appropriate methodologies can be selected in advance of teamwork. More generally, teams need clarity of purpose and direction in order to work together effectively, and working to achieve this clarity is all part of effective planning as a group sets off to address complex societal issues (Warfield, 1976, 2006; Hackman, 2002).

As the teamwork process unfolds, other challenges are notable, including those associated with engagement, communication, and resistance and fears. For example, CINSU members noted the inherent inertia of a system acts as a barrier to change and innovation, and awareness of these dynamics is important for organization change (Wong-MingJi and Millette, 2002). A lack of active engagement limits the potential of a team to integrate knowledge and skills, and lack of accountability and incentives that promote cooperation can limit engagement.

Fundamental communication patterns are important, including openness and listening with curiosity during team collaborations, and engaging critically with team members.

Effective teams include members who are willing to speak out and take risks in sharing their knowledge and critical reflections with one another (Edmundson, 1999). The diversity of language used and the degree of consistency in terms of style, method, and skill levels in a team can also present challenges, and practice communicating with open curiosity is important when embracing the diverse landscape.

In this context, we come to appreciate the challenge of heterogeneity and the need for collaborative methodologies that support shared understanding.

However, heterogeneity is not always easy to embrace, and there is often resistance to methods or content perceived as less valid, reliable, or prestigious.

Again, openness to alternative approaches is important, including those which may not typically be used in one’s own field. In modern technological societies, where science is often confused with science fiction, the lure of a “solutionist” approach can be strong, but solutions to complex societal problems don’t come easy and a solutionist approach can negatively impact the process of collaborative teamwork if people become impatient for the ‘quick fix’.

At a deep level, resonating with challenges in our current political milieu, conflict between ideological assumptions at the paradigmatic and prescriptive levels is a major challenge that negatively influences all other challenges in the system. Unless we take some time out to explore and address our assumptions as a team, our potential for collaboration will be negatively impacted. More generally, infrastructures supporting collaboration are needed, and although technology appears to provide solutions when it comes to addressing complex societal problems the reality is there are few platforms that truly enable effective teamwork.

A pragmatic approach to societal problem solving should always recognize that genuine human progress is most often collaborative and the result of people utilizing their diverse knowledge and skills in environments that support effective communication and teamwork (Ostrom, 1990; Hogan, Hall, and Harney, 2017; Mulgan, 2018).

Like many others working in the field, we recognize the need to better design and support teams in efforts to resolve societal problems. As noted by John Dewey (1916), a democratic society requires an educated population who can collaborate, deliberate and learn together. If transdisciplinary teams are to become the leading edge of societal problem-solving efforts in the future (Khoo, 2017), we need to work now to build the educational and political infrastructure that supports teamwork. Beyond all our disciplinary and political divides, developing the strategies and behaviors that support teamwork and cooperation will be essential for the future survival, adaptation, and flourishing of Homo sapiens.

References

Featured Paper

Hogan, M. , Broome, B. , Harney, O. , Noone, C. , Dromgool‐Regan, C. , Hall, T. , Hayden, S. , O’Higgins, S. , Khoo, S. , Moroney, M. , O’Reilly, J. , Pilch, M. , Ryan, C. , Slattery, B. , Van Lente, E. , Walsh, E. , Walsh, J. & Hogan, V. (2018). Integrating Content Expertise and Methodological Expertise in Team‐Based Settings to Address Complex Societal Issues—A Systems Perspective on Challenges. Systems Research and Behavioral Science. doi:10.1002/sres.2522

Other references

Bernstein, J. H. (2015). Transdisciplinarity: A Review of Its Origins, Development, and Current Issues. Journal of Research Practice, 11, 1-17.

Broome, B. J. (1995a). Collective design of the future: Structural analysis of tribal vision statements. American Indian Quarterly, 19, 205-228.

Broome, B. J. (1995b). The role of facilitated group process in community-based planning and design: Promoting greater participation in Comanche tribal governance. In L. R. Frey (Ed.), Innovations in group facilitation: Applications in natural settings (pp. 27-52). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Broome, B. J. (2006). Applications of Interactive Design Methodologies in Protracted Conflict Situations. Facilitating group communication in context: Innovations and applications with natural groups. Mahwah, NJ: Hampton Press.

Broome, B. J. (2017). Moving from conflict to harmony. In. X, Dai &. G.M. Chen (Eds) Conflict Management and Intercultural Communication: The Art of Intercultural Harmony, (pp. 13-28). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Broome, B. J., & Christakis, A. N. (1988). A culturally-sensitive approach to tribal governance issue management. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 12, 107-123.

Broome, B. J., & Cromer, I. L. (1991). Strategic planning for tribal economic development: A culturally-appropriate model for consensus building. International Journal of Conflict Management, 2, 217-234.

Broome, B. J., & Fulbright, L. (1995). A multistage influence model of barriers to group problem solving: A participant-generated agenda for small group research. Small Group Research, 26(1), 25-55.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Macmillan.

Domegan, C., McHugh, P., Devaney, M., Duane, S., Hogan, M., Broome, B. J., ... & Piwowarczyk, J. (2016). Systems-thinking social marketing: conceptual extensions and empirical investigations. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(11-12), 1123-1144.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

Forsyth, D. R. (2014). Group dynamics (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Glendon, A.I. & Clarke, S.G. (2017). Human safety and risk management: A psychological perspective. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Hackman, R.J. (2002). Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hogan, M. J., Harney, O., & Broome, B. (2015). Catalyzing Collaborative Learning and Collective Action for Positive Social Change through Systems Science Education. In: R. Wegerif, J. Kaufman, L. Li (Eds). The Routledge Handbook of Research on Teaching Thinking (pp. 441-456). London: Routledge.

Hogan, M. J., Hall, T., & Harney, O.M. (2017). Collective Intelligence Design and a New Politics of System Change. Civitas Educationis, 6(1), 51 - 78.

Khoo, S.-M. (2017). Sustainable knowledge transformation in and through higher education: A case for transdisciplinary leadership. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 8(3), 5-24.

Leyden, K. M., Slevin, A., Grey, T., Hynes, M., Frisbaek, F., & Silke, R. (2017). Public and Stakeholder Engagement and the Built Environment: a Review. Current Environmental Health Reports, 1-11.

Nowak, M. A. (2006). Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science, 314(5805), 1560-1563.

Mulgan, G. (2018). Big Mind: How collective intelligence can change our world. Princeton University Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pettersson, M. (1996). Complexity and evolution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pettit, P. (2014). Just freedom: A moral compass for a complex world. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

Reason, J.T. (1987). The Chernobyl errors. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 40, 201-206.

Richerson, P. J., & Boyd, R. (2005). Not by genes alone: how culture transformed human evolution. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press.

Reed, M. S., Vella, S., Challies, E., de Vente, J., Frewer, L., Hohenwallner-Ries, D., Huber, T., Neumann, R. K., Oughton, E. A., Sidoli del Ceno, J. and van Delden, H. (2017). A theory of participation: what makes stakeholder and public engagement in environmental management work? Restoration Ecology. doi:10.1111/rec.12541

Warfield, J. N. (1976). Societal systems: planning, policy, and complexity. New York: Wiley.

Warfield, J. N. (2006). An introduction to systems science. Singapore: World Scientific.

Wong-MingJi, D. & Millette, W. R. (2002). Dealing with the dynamic duo of innovation and inertia: The "in-" theory of organization change, Organization Development Journal, 20(1), 36–55.