Attention

Sparks of Genius Challenge #2: Non-Visual Observing

When it comes to imaginative skill, practice is an eye-opener.

Posted June 26, 2015

Welcome to the Sparks of Genius Challenge!

Join us in stimulating imaginative skills with regular practice (20 minutes a day, an hour a week, a half-day a month). Our second set of observing challenges will push beyond the visual observing of challenge #1 to observing with senses other than our eyes—with ears, nose, tongue, and skin. But first, let’s debrief that last challenge to visual observing.

Recapping the last challenge.

If you took challenge #1, you’ve probably already discovered that our three levels—novice, practitioner, master—have little to do with age. When it comes to sensory experience or to its rendering, a child may be a practitioner, an adult a novice. Moreover, someone who feels confident in their observing abilities might still appreciate the challenge of a novice exercise. Someone who feels they have much to learn might be drawn to a master challenge. Given so many ways of observing and so many ways of exercising and recording sensory experience, there are always additional imaginative adventures for young and old, beginner and proficient.

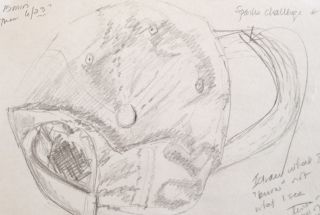

As a case in point, one of us – Michele – chose to take on the master challenge in our last post, devoting about an hour to drawing her running hat and copying a photograph of a surfer riding a wave. Michele really cannot draw. Or, put it another way, she rarely exercises that skill. Though her drawing of a hat is recognizably a hat, the proportions are out of whack and the shading poorly handled. And yet, she learned something interesting by drawing what she observed, something one might only realize by going through the process. The bill of the hat turned out all wrong. Why? Because she drew what she “knew” rather than what she “saw.” Note, for instance, that she drew the stitching in parallel to the edge of the bill, when in fact, from her angle of vision, the stitching disappeared off the far side.

And about those proportions. Unh unh. Though she purposefully eyeballed the length of the hat crown and compared it to the length of the bill before setting pencil to paper, things didn’t turn out that way. Again, it seems, she drew without really privileging the information received from her eyes. And when it came to drawing the surfer dude, she decided to copy the photograph upside down first, expecting the second attempt, right side up, would be that much better. Yet the relative proportions of legs to torso to arms proved much more accurate in the upside down copy.

Take-aways.

First, Michele should draw more!—maybe that 20 minutes a day would be a good idea, especially if she wants to heighten her visual experience of the world. Practice makes better.

Second, it is very difficult to ignore previous knowledge or previous sensory input during an observing experience. When one has already handled a baseball cap, it is very obvious that the stitching reiterates the curve of the bill. In other words, it is difficult to see with fresh eyes, as if for the first time.

Third, changing the context helps. Observing a photo upside down, for instance, renders the object—the surfer’s body-- temporarily impervious to the assumptions of previous knowledge. Thus, to see a thing freshly may be as easy as observing it from an unusual angle, in unexpected circumstances.

A further challenge.

Observing is never a purely visual act. What we see is affected by what we have touched with our hands and felt within our bodies. The same goes, of course, for what we don’t see, but hear, smell or taste. The more we exercise observing with each of our senses one at a time, the more we will observe with them all at the same time. Our second set of observing challenges therefore focuses on non-visual forms of observing: aural (sound), tactile (shape, temperature, texture, etc.), kinesthetic (shape, weight, movement), olfactory (smell), or gustatory (taste).

Novice:

Have someone you know dip Q-tips into various spices without letting you see which ones. Then blindfold yourself and have your friend hand you one Q-tip at a time. See if you can identify each of the spices. Does it help to practice?

Practitioner:

Ask some friends or family members to place a few hand-sized objects in a pillow case—without telling you what they are. Now, without peeking, place a hand inside and feel one thing at a time. Can you identify what it is? Can you guess all the objects in the pillow case?

[You might also try feeling objects from the outside of the pillow case, which adds a layer of complexity to your observing. A somewhat more difficult version of this exercise is to have a friend put 1, 2 or 3 objects into small boxes. Your challenge is to use the sound and feel of the object(s) moving inside the box to identify number and shape or, if you are really good at aural and kinesthetic observing, to name the object(s).]

Master:

Heighten your attention, à la Konstantin Stanislavsky. The Russian actor-director had his students collect as much sensory information as they could about an object or objects in a room and describe their experience in detail. Turning off the lights, or leaving the room, they described again. Then they observed again, looking for what they had forgotten—or missed all together.

Try this. For five minutes or so, study an object’s form, its coloring and the sounds it makes, the way it smells or tastes, the way it feels in the hand. Then remove the object and try to recall one by one as many details as possible. Describe your object verbally, or draw it, or write about it. For a real challenge, describe the object by making its shapes, textures and movements with your body. Then, go through the process again, pushing yourself for finer and finer perceptions.

“Such an effort,” Stanislavsky wrote, “causes you to observe the object more closely, more effectively, in order to appreciate it and define its qualities.”

As always, we welcome your feedback. Tell us what your experiences reveal about the imaginative act of observing!

© 2015 Michele and Robert Root-Bernstein