Artificial Intelligence

Trading Semen: The Tale of Artificial Insemination

Sperm injections still play an essential part in assisted reproduction.

Posted November 21, 2019

Lazzaro Spallanzani, 18th Century Italian priest and natural scientist, famously provided direct evidence that eggs will not develop without semen. By fitting male frogs with tight taffeta pants, he showed that eggs shielded from semen did not produce tadpoles. This was, incidentally, an early application of barrier contraception. More importantly, Spallanzani also demonstrated the principle of artificial insemination. He retrieved semen that males discharged into their taffeta pants and painted it onto eggs, which then yielded tadpoles.

But fertilization is external in frogs and other amphibians. Performing artificial insemination with mammals, which all have internal fertilization, is more challenging. In 1784, Spallanzani reported the first recorded successful procedure of this kind, inseminating a female dog that subsequently gave birth to three puppies after the expected two-month pregnancy.

Origins of human artificial insemination

Because mammals have internal fertilization, artificial insemination (AI) — injecting semen into the female reproductive tract — is the simplest type of assisted reproduction. AI has a long history in animal husbandry, where it is now widely and routinely employed for selective breeding, and in laboratory studies. Reportedly, it was used for horse breeding in 14th Century Arabia, but early documentation is sparse. After Spallanzani’s experiments, over a century passed before routine practical use of AI was reported. In 1899, Russian veterinarian Il’ya Ivanovich Ivanov initiated long-term trials with horses, and by 1907 he had also investigated AI in dogs, foxes, rabbits, and chickens. However, unsuccessful attempts to fertilize chimpanzees with human semen tarnished his reputation.

In 1785, renowned Scottish surgeon John Hunter achieved an early breakthrough with the birth of a child using human AI. However, the procedure did not become established for routine treatment of human infertility until the mid-20th Century.

Ethical issues

AI itself is relatively uncomplicated, but moral issues initially spurred strong opposition. Inseminating a woman with her own husband’s semen (AIH) met little resistance. When the male partner produces few sperms but is not utterly infertile, semen can be collected and enhanced for transfer. But when the male partner is completely infertile, artificial insemination by donor (AID) with semen from another man of proven fertility is needed. Up until the middle of the 20th Century, many religious leaders and others branded AID as a form of adultery. Moreover, legal issues regarding paternity arose. As recently as 1948, an anonymous commentary in Nature journal cited a report commissioned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, stating that AID “is wrong in principle and contrary to Christian standards ……… early consideration should be given to framing of legislation to make the practice a criminal offense". Such opposition greatly delayed the general acceptance of AID.

Ethical issues with AID are not confined to religious and legal aspects. From the outset, woefully inadequate controls let malpractice thrive. Gena Corea’s 1985 book The Mother Machine and Elizabeth Yuko’s 2016 article in The Atlantic recount astounding details of the first successful AI in the USA. The woman, an unnamed 31-year-old Quaker in Philadelphia, was examined for infertility by Dr. William Pancoast of Jefferson Medical Colleges. Having finally concluded that the woman was actually fertile, Pancoast discovered that the husband’s semen entirely lacked sperms. In 1884, he summoned the woman for another “examination”, anesthetized her with chloroform and — without her consent — injected semen into her womb with a hard rubber syringe. One of six senior medical students in attendance (“the best-looking member of the class”) provided the sample. In due course, the woman gave birth to a healthy son. The story first became public knowledge 25 years later when Medical World published a letter from Addison Davis Hard — one of the students present at the insemination.

Over-used donors

Inadequate oversight of AID continues, so it is hardly surprising that there have been multiple examples of excessive use of semen from a single donor within a limited region. This is outrageous because of the danger of “inadvertent consanguinity”: men and women sired by the same anonymous donor might unwittingly meet, become partners and have children. In fact, the label “semen donors” is misleading, especially in the USA, because sample providers are mostly semen vendors. The current US market price is around $100 a sample.

An unanticipated spin-off from modern sites such as Ancestry and 23andMe, which provide genetic information based on DNA analyses, is that many individuals are now discovering previously unknown relatives. Anonymous AI is often an explanation. CBS News recently reported that a former donor (now a physician himself) filed a lawsuit after discovering that he had sired at least 17 children, all living in the same state. As a medical student 30 years ago, the fertility clinic at Oregon Health and Science University had recruited him to donate semen for AID and research.

A particular arresting case, reported by Rene Chun in 2018, involves Peter Ellenstein, Uber driver and self-styled “Sperminator”. In 1987-1994, as a struggling would-be actor in Los Angeles, he was an unusually prolific sperm vendor. Recognized as a “Proven Donor”, he provided as many as 5 samples a week for two local sperm banks. Decades later, thanks to DNA testing and the Donor Sibling Registry (which has documented over 20 AID offspring clusters with 75 siblings or more), many of Ellenstein’s indirectly sired descendants contacted him. Their number began at a dozen and swelled to a score, but the real total could be hundreds. An upcoming “family” gathering will provide a springboard for a docuseries already under contract. Ironically, Ellenstein’s one-time side job as an aspiring actor might bring him the closest he’s ever been to stardom.

Most culpable of all are the many fertility doctors who blithely inseminated patients using their own semen. Earlier this year, Jacqueline Mroz and Mihir Zaveri separately reported several cases in The New York Times. Remarkably, in the USA such fraudulent conduct is usually not illegal, although a few states have belatedly begun to pass laws criminalizing it as a form of sexual assault.

And then there is the stunning case of Bertold Wiesner (1901–1972), a major contributor to research into human fertility and pregnancy diagnosis. It is estimated that, over a 20-year period, Wiesner fathered up to 600 offspring. He was the anonymous donor of semen that his obstetrician wife Mary Barton used to inseminate female patients at her private practice in London. At that time — facing religious opposition and calls for prohibition — they conducted AI in complete secrecy. Rampant fatherhood by proxy earned Wiesner the dubious distinction of occupying the #1 spot in Wikipedia’s “List of People with the Most Children”.

Progress with AI

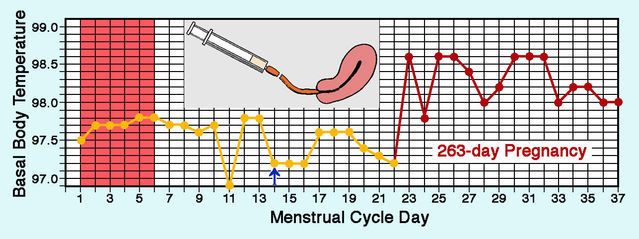

Although AI remains relatively straightforward, various refinements have occurred. From the outset, a primary concern was optimizing the time of insemination during the menstrual cycle to maximize pregnancy rates. Initially, physicians aimed to inseminate close to natural ovulation, which could be detected from basal body temperature (BBT), but only after the event. So ovulation time was estimated from an average across several cycles. Routine detection of ovulation from hormone levels improved matters distinctly in the 1960s. Taking the next step, gynecologists now generally induce ovulation hormonally rather than relying on its natural occurrence somewhere around midcycle.

Semen storage at very low temperature (cryopreservation) was another crucial advance, becoming the medical norm in the late 1980s. Sperm banks then emerged to store and sell frozen sperm, sometimes on a grand scale. In the USA, three very big sperm banks now dominate the market. Yet it has long been known that freezing semen for AID radically reduces the pregnancy rate obtained with fresh semen. A 1984 paper by Michael Richter and colleagues reported direct comparisons of fresh and frozen semen with women patients serving as their own controls. The success rate with fresh semen was 18.9% but only 5.0% with frozen semen. Despite improvements in cryopreservation, a striking advantage of fresh semen persists. Success rates of AID remain low — 20% per cycle at best, with about 6 insemination cycles needed to reach a 90% pregnancy rate — so it is odd that frozen semen has extensively replaced fresh semen.

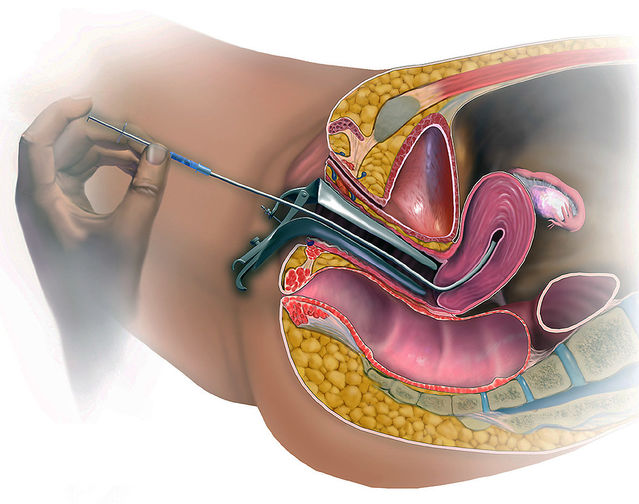

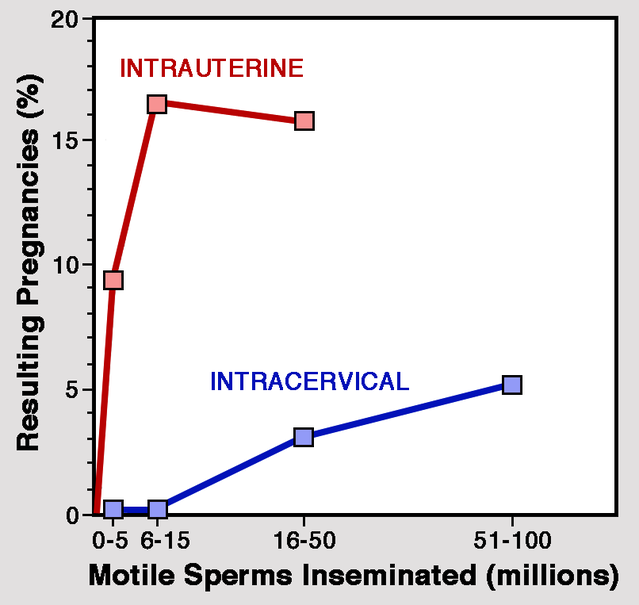

The insemination process has also undergone radical change. Originally, semen was either deposited deep in the vagina or, more likely, introduced into neck of the womb (cervix). However, intracervical insemination (ICI) was increasingly replaced by injection directly into the womb — intrauterine insemination (IUI).

IUI has the considerable advantage that conception is more likely when sperm numbers are particularly low. In 1990, William Byrd and colleagues reported results from a direct comparison with frozen donor sperm. Pregnancy rate per cycle with IUI was more than doubled compared to ICI: 9.7% instead of 3.9%.

It was soon discovered that when semen was injected directly into the womb certain products of the prostate gland (prostaglandins) could cause cramping. So washing to remove seminal fluid before IUI is now standard practice. But it is unfortunate that direct insemination into the womb bypasses the natural filtering action of the cervix, which removes physically deformed sperms.

Unknown territory

Despite extensive use, some underlying processes in AI await clarification. Take just one example: In 1998, gynecologist Fu-Jen Huang and colleagues reported a comparison of pregnancy rates between couples treated with AI alone and couples who followed AI with coitus 12-18 hours later. When the woman was inseminated with relatively few motile sperms (below 40 million), follow-up coitus boosted the pregnancy rate, But no increase occurred with inseminations of more than 40 million motile sperms. For this and other reasons, the storage of large numbers of sperms in blind channels (crypts) in the cervix after coitus demands a proper investigation. [See my blog piece What Dogs Can Tell Us About Sex and Conception, posted March 03, 2016.]

References

Anonymous (1948) Artificial human insemination. Nature 162:790-791.

Barton, M., Walker, K. & Wiesner, B. (1945) Artificial Insemination. British Medical Journal 1:40-43.

Byrd, W.B., Edman, C., Bradshaw.K., Odum, J., Carr, B. & Ackerman, G. (1990) A prospective randomized study of pregnancy rates following intrauterine and intracervical insemination using frozen donor sperm. Fertility & Sterility 53:521-527.

Chun, R. (2018) This sperm donor didn’t think much about his side gig — until 20-plus children surfaced. Los Angeles Magazine, September 10.

Corea, G. (1985) The Mother Machine: Reproductive Technologies from Artificial Insemination to Artificial Wombs. New York: HarperCollins.

Donor Sibling Registry — Link to Website:

https://www.donorsiblingregistry.com/about-dsr/history-and-mission

Hard, A.D. (1909) Artificial impregnation. Medical World 27:163-164.

Kleegman, S.J. (1954) Therapeutic donor insemination. Fertility & Sterility 5:7-31.

Mroz, J. (2019) Their mothers chose donor sperm. The doctors used their own. The New York Times, August 21.

Richter, M.A., Haning, R.V. & Shapiro, S.S. (1984) Artificial donor insemination: fresh versus frozen sperm; the patient as her own control. Fertility & Sterility 41: 277-280.

Yuko, E. (2016) The first artificial insemination was an ethical nightmare. The Atlantic, January 8.

Zaveri, M. (2019) A fertility doctor used his sperm on unwitting women — Their children want answers. The New York Times, August 30.