Environment

Wise and Wonderful

The riots in the U.S. make lots of sense—to biologists.

Posted June 2, 2020

Did you know that there's a secret verse to the hymn, "All Things Bright and Beautiful," that no one sings any more?

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate;

God made them, high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.

The hymn was written by Mrs. Cecil Frances Alexander in 1848, at the height of the Irish potato famine. This means that the "poor man," starving at the gate of that castle, could be seen out of her window. She could have drawn the attention of her husband, then Bishop of Derry, to his plight, had she so wished.

Ironic indeed. God may have been happy with all creatures great and small, and the ordering of human estates into high and lowly—but what if the humans themselves are less convinced of the cosmic justice of this?

He gave us eyes to see them

Rioting makes no sense to some people. "It’s not reasonable," I was told recently by a famous statistical modeler, and champion of reason.

Relax. I’m not going to make fun of the "humans are not doing what my model predicts, the humans must be broken" school of behavioral science. I’ve done that before. And, I’m not going to offer a political, moral, or even tactical, position on the riots currently breaking out across the USA. There’s no shortage of all of these available at any nearby Twitter handle.

I don’t have anything useful to add to those accounts. What I do, as an ethologist, is study behavior in natural settings, and try to make sense of that behavior in terms of that organism’s evolved goals, and perceived threats.

"But it doesn’t make sense to burn down your own neighborhood," cry the pundits. Clearly such people want some sense to be made of it, which is a very different thing from a justification. What sense does it make for an organism to destroy its own environment? Let me offer some perspective based on the work I, and my team, did on the 2011 UK riots.

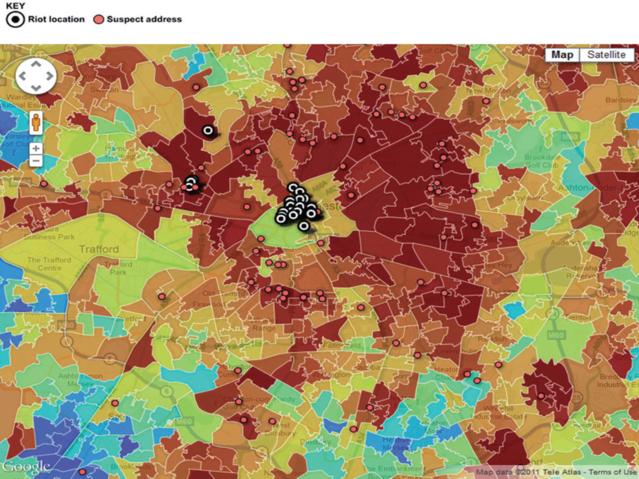

I should stress that I haven’t looked at the data from the USA but, if it doesn’t fit the pattern of what we found 10 years ago in the UK, then I’d be much surprised. Back then we analyzed the backgrounds of nearly 1000 arrested rioters, and I cross-referenced these data with the local markers of relative deprivation (education, housing, food, health, environment, income, and crime) both in the places where they rioted, and their homes. Here were some key take-home messages.

- Those arrested were not, for the most part, destroying their own neighborhoods. They were coming into other neighborhoods and burning those down.

- The neighborhoods they came from were disproportionately deprived ones, and those markers were obvious from demographic and visible street-level data.

- Rioting worked, somewhat. There was subsequent investment to those deprived areas bringing them more in line with surrounding areas in terms of facilities although this was by no means universal or even particularly sensibly handled.

All (social) creatures great and small

I’ve found it’s hard for people to appreciate that they can be living in the same rough, geographical area, but be occupying different worlds.

The technical term for the world that appears to that particular organism, in terms of its threats and opportunities, is called its umwelt. Say I’m in my friend’s garden (this is before the lockdown) having a gin and tonic. A bee flies around me collecting pollen. We are in the same garden, but in very different umwelts. The bee sees opportunities for nectar that I don’t, and has threats that don’t apply to me (such as predatory birds). I have opportunities (like that G&T) that mean nothing to the bee, but also potential threats (like that loose step that I almost tripped on last time) that mean nothing to her.

Here is the first crucial thing to appreciate: With humans, those threats and opportunities are largely in terms of social realities. Things like access to health care, food quality, education, job opportunities.

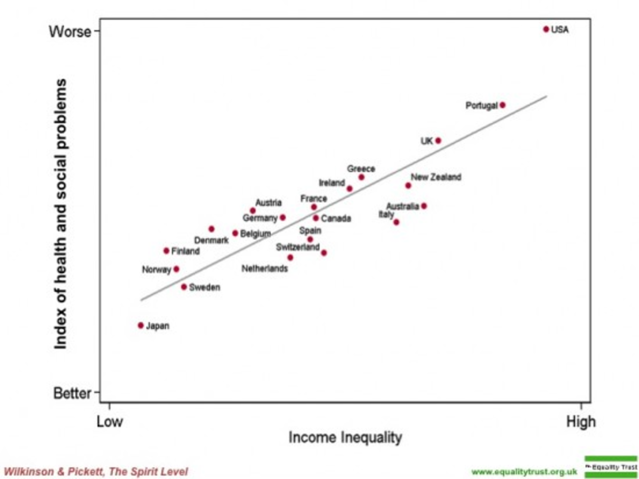

Here is the second crucial thing to appreciate—when it comes to those sorts of things, humans are laser-guided to inequalities. By now, most of you have probably seen Frans de Waals wonderful demonstration of how social primates (in this case capuchin monkeys) are exquisitely sensitive to perceived inequality. But—if you haven’t seen it—take a minute.

The human response to perceived inequality can be instant, like that violent response, but there is increasing evidence that the response goes far deeper than that. To simplify enormously a complex field—there is good evidence that humans, along with other organisms—respond to signals of likely life trajectories by a series of internal switches that prepare us for a likely life of ease and trust, or a likely one of danger and mistrust. Live fast, die young, or take your time and enjoy the ride.

Imagine that you are renting a car for a long journey. Do you get a sporty open-topped vehicle and take it easy, relishing the view, or a rough, all-terrain semi-tank of a car? There’s a catch, you don’t know if it’s going to be a bumpy road through hostile territory, barely navigable, or a nice long stretch of highway with plenty of gas stations. You’d opt safely, yes? Well, now imagine that you know that the journey is going to be smooth going—you’d rent the comfortable sporty number. Take in some purple-headed mountains, and tall trees in the greenwood.

Our genes have gone down a lot of roads for a very long time, before finding themselves in the particular vehicle that is us. And—they seem to have developed ways of deciding what the likely road ahead is and prepare accordingly—by turning on and off particular mechanisms. Human beings live in social worlds like fish live in water. A lot of these markers to future feast or famine are social ones. Perceived inequality runs through them like a city name on a stick of rock. The USA, for all its wealth, has the highest level of inequality in the world.

Live fast and die young is not a metaphor, incidentally. For instance, one hard-to-miss measure of fast life history trajectories is simple life expectancy. Averages here can be misleading. For example, the average male life expectancy in Houston (where George Floyd came from) is about 78 years—roughly the average for the USA. But different districts within Houston can differ between nearly 69 and 89 years.

Same planet, different worlds. It used to be true (it probably isn’t now) that a young black man on the streets of Compton had a higher life expectancy if he was put in death row, than if you left him where he was. At some level, he would be aware that playing by the rules was not going to result in his being a stockbroker.

And your body picks up on these markers. It ages faster. It makes the girls reproduce earlier, and the boys more likely to take risks. That’s the biological backdrop against which specific violent behaviors need to be understood. That is not, of course, the final word on the matter—but it’s a word that isn’t heard enough.

References

https://www.christiantoday.com/article/the-dark-secret-of-a-great-hymn-…

Incidentally, that date-1848, gives the lie to the idea that the hymn was written as a counterblast to Darwin’s Origin of Species, which didn’t come out until; over ten years later.

Life History Theory has become a growth field in psychology—cutting through tired old battles of ‘innate/learned’. As always happens, things get tested and don’t work, others need to be theoretically clarified and so on. I should stress, because some people persist in seeing this as a problem, that this is how science works. No-one should take the white heat of theoretical clarification for ‘debunking’ or any other such twaddle (sorry to be grumpy, but this sort of treating Science as a zero-sum game with winners and losers has been getting on my nerves recently).

For a good overview of recent issues in LHT see especially Del Giudice, M. (in press).

Rethinking the fast-slow continuum of individual differences.

Evolution and Human Behavior. Available at https://marcodg.net/publications/

For a foundational paper on L:HT see Stearns, S. C. (1976). Life-history tactics: a review of the ideas. The Quarterly review of biology, 51(1), 3-47.

For some excellent empirical work looking at the effect of accelerated LHT on adjacent neighborhoods in Newcastle see

Nettle, D. (2010). Dying young and living fast: Variation in life history across English neighborhoods. Behavioral ecology, 21(2), 387-395.

For foundational work on the effect of local violence has on accelerated life histories see Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Homicide. Transaction Publishers.