Adolescence

Why Did Teen Suicides Decline Sharply from 1990 to 2005?

Was the digital revolution a cause of the decline in teen suicides?

Posted October 1, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

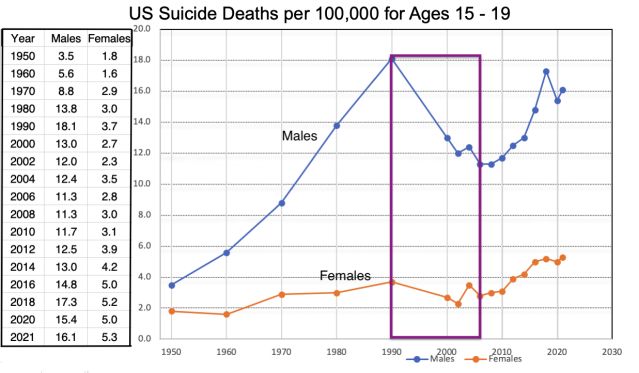

In my last post I initiated a discussion of the changes in suicide rate for U.S. teenagers over the years from 1950 to the present, which are charted in the graph shown below. I discussed there ideas about why boys commit suicide at much higher rates than girls, and then I discussed theories about why the suicide rate, especially for boys, rose so sharply from 1950 to 1990.

Concerning the increase in suicide rates between 1950 and 1990, I discussed the change in death recording theory (that earlier in the century suicides were often recorded as accidents); the guns in home theory (that increased availability of guns may have led to increased suicides); the decline in religious affiliation theory; and the change in family structure theory (that a rise in divorces or in single-parent families, or a decline in the presence of a parent at home) may have caused the increase.

The evidence regarding each of these theories led me to conclude that none of them likely accounted for much of the change in suicide rate. The theory I presented there as by far the most compelling is that which I labeled, the constraints on independence theory.

My main contention, in the last post, was that over the 40 years from 1950 to 1990, children and teens were increasingly deprived of opportunities for free play and other independent activities (activities not governed or monitored by adults)—the kinds of activities that promote immediate happiness and also allow kids to develop the courage, confidence, and a sense of agency required to meet the challenges of life with equanimity.

Over those 40 years, we were increasingly “protecting” children from what we perceived as possible dangers, increasingly teaching them and guiding them, leaving them ever less opportunity to learn how to create and direct their own activities and solve their own problems. The result, over time, was a decline in what psychologists call an internal locus of control—the sense of being in control of one’s own life and able to solve life problems as they arise.

Much research shows that people of all ages who lack a strong internal locus of control are vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and suicide. Without opportunities to learn how to control their own activities and solve their own problems, people develop a sense of helplessness, which is almost the definition of anxiety, and of hopelessness, which is almost the definition of depression. More than a decade ago I presented a version of this theory in the American Journal of Play (Gray, 2011), and, much more recently, an updated version, supported by multiple lines of research evidence, in the Journal of Pediatrics (Gray, Lancy, & Bjorklund, 2023).

Now, for the first time, I present what I think is a novel theory for why the suicide rate, especially for boys, declined sharply from about 1990 to about 2005. My theory, in brief, is that computer technology and video games brought a renewed sense of freedom, excitement, mastery, and social connectedness to the lives of children and teens, thereby improving their mental health.

Teens Were Leaders of the Digital Revolution

If you are old enough to have been parent to a teenager around the year 1990, you may recall that your kid was the one clamoring for a home computer. Kids nearly always, everywhere, glom on to new technology and become skilled at it before adults do. (This may be a topic for a future post.) Once you brought such a device into your home, your kid most likely learned to use it before you did, and when you finally, gingerly, tried to learn it your kid taught you how. Wow. A role reversal. Your kid is the master; you’re the apprentice.

I recall around that time walking into the newly established computer sections of department stores, like Sears (remember Sears?), and finding that the salespeople were teenagers. I also remember that when the Boston College Psychology Department finally (belatedly) got up to speed on computer use at about that time or a little before, we hired a teenager to figure out how to use the new technology and then teach us professors how. That was before the university acquired a fleet of professional information technologists.

So, I suggest, there was a time when, to a considerable degree, teenagers (and sometimes younger children, too!) were valued for their remarkable ability to figure out this new technology and teach it to us slower-witted adults. That must have increased kids’ sense of agency and decreased their depression and despair.

By about 2005 or somewhat after, the kids who were teens in the 1990s had become adults, perhaps with their own kids. The next batch of teens were not in the same position as the earlier batch. Their parents already knew how to use computers. The department stores and universities were hiring adults, not kids, as their experts. The power of teens as digital natives declined, as an increasing number of adults were also digital natives. The special role of teens declined and maybe that helps explain why depression and suicide rates started trekking upward again (more on that in in a future post).

Video Games Restored a “Culture of Childhood”

Sociologists and anthropologists who have studied children worldwide have observed that children normally—in other cultures and in ours until about half a century ago—grew up in a “culture of childhood.” That is, they grew up in a world where they had almost continuous social interactions with other children, outside of adult control. This is where they learned how to initiate their own activities, solve their own problems, create and follow rules, get along with peers, and deal with bullies. In short, this is where they acquired the skills of independence required, eventually, for adult life.

One way of describing the changes in kids’ lives from about 1950 to about 1990 is that over this time we, as a society, were gradually destroying the culture of childhood—by isolating kids at home, depriving them of freedom to roam and play with other kids, and occupying them ever more with adult-controlled activities. (For more on the culture of childhood and how we almost destroyed it, see here.)

Following this thread, one way of describing changes in kids’ lives beginning around 1990 is that digital technology, to a considerable degree, restored a culture of childhood. Kids still could not engage in adventures and connect with other kids outdoors, because of our unreasonable restrictions on them, but they could engage in adventures and connect with other kids digitally, especially through video games.

Kids glommed onto computers for many reasons, but the biggest reason was video games. Gaming consoles and then computers provided foundations for ever more exciting, ever more challenging, and ultimately ever more social video games. In an article on the history of gaming (here), Riad Chichani wrote:

““Multiplayer gaming over networks really took off with the release of Pathway to Darkness in 1993, and the “LAN Party” was born. LAN gaming grew more popular with the release of Marathon on the Macintosh in 1994 and especially after first-person multiplayer shooter Quake hit stores in 1996. By this point, the release of Windows 95 and affordable Ethernet cards brought networking to the Windows PC, further expanding the popularity of multiplayer LAN games.”

Video gaming became the glue that brought kids together again, not outdoors, where they were still generally not allowed, but indoors. Even before multiplayer games over the Internet were possible, video games were already intensely social. Kids often played them together at the same console. And when they saw one another at school and had a bit of free time they talked about games. Video games were the common denominator that defined a new culture of childhood. The fact that most adults didn’t understand the games and many disapproved of them, of course, added to the excitement. Kids owned these games. They had, once again, their own world.

The Power of Video Games Lies in Their Ability to Satisfy the Three Basic Needs for Mental Well-Being

Near the beginning of the 21st century, researchers conducted extensive studies aimed at understanding why video games were so popular. What were kids getting from them?

One group of researchers (Przybylski, Rigby, & Ryan, 2010) approached this question from the vantage point of Basic Psychological Needs Theory. According to this theory—which is supported by literally hundreds of research studies with people of all ages—mental health depends on the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: autonomy (the freedom to make one’s own choices), competence (the sense of being good at a self-chosen task), and relatedness (feeling connected to peers). In an extensive set of studies—including surveys and focus-group discussions with kids about why they like the games, analyses of the difference between games that became most popular and games that flopped, and laboratory studies in which kids played video games and reported on their feelings before, during, and after the game—the researchers concluded the games are popular because they are so powerful in satisfying the three basic needs.

Here is an elaboration:

• Autonomy. For kids who had little previous autonomy, video games were a windblast of freedom. They chose their own games. They chose how to play them; no adult was standing there telling them what to do. As games became more complex, the choices within games became infinite. Every game was a self-created adventure.

• Competence. The games were difficult. In the research studies, many kids pointed to the challenges and the sense of mastery in meeting those challenges as the primary motivating force. Even to begin playing a game, kids had to figure out how to set it up and how to master the controls. And then the game itself involved multiple mental challenges. The games were organized such that the challenges were never ending. When you met the challenges of one level to your satisfaction you moved on to a higher level, where the challenges were even greater. As one middle-schooler said when asked why he liked playing video games (Olson, 2020), “I feel like I actually did something right!” Consistent with the claim about the mental challenges of video games, dozens of research studies show that the games build cognitive skills, such as ability to make quick but accurate decisions, ability to distinguish what is important from distractors, and ability to reverse course when one approach is not working (see here and here).

• Relatedness. I discussed this, above, in describing how the games restored a culture of childhood. In the surveys and focus-group meetings, many kids pointed out that making and connecting with friends was one of their motives for playing the games. Some pointed out that even games played alone became topics of conversation with other kids when not playing. As one middle schooler explained: “If I didn’t play video games—it’s kind of a topic of conversation, and so I don’t know what I’d talk about.” And another said: “You can start a conversation by asking, ‘Do you own a system, a game system?’ If he says ‘yes,’ then 'What kind?’” (Olson, 2010.)

But do video games actually, in the long run, improve mental health? The research conducted to date strongly suggests “yes.” For a summary of some of that research, see my Psychology Today post here. For example, a large-scale study, of over 3,000 children ages 6 to 11, conducted by Columbia University’s Mailman School of Mental Health, revealed that children who played video games for more than five hours a week evidenced significantly higher intellectual functioning, higher academic achievement, better peer relationships, and fewer mental health difficulties than those who played such games less or not at all (Kovess-Masfety et al., 2016).

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

I have summarized here what I see as compelling reasons to believe that the digital revolution and especially the introduction of exciting, challenging, and socially engaging video games played a big part in the improved mental health and reduction in suicides among teens, especially boys, from about 1990 to about 2005.

I’m pretty convinced that this is the major cause of reduced suicides in this period, but it may not be the only cause. In an article published more than a decade ago, Jack McCain (2009) suggested, with some evidence, that an increased use of SSRI antidepressants during this time may have played a role. This is an idea worthy of closer examination.

In a future post, I’ll look at the final part of the depression curve on the graph—the rapid rise of suicides beginning about 2010. We see there a bouncing back to, eventually, almost 1990 levels. Why? Some think the only possible answer must be smartphones and social media. I have some other ideas.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions. Psychology Today does not allow comments, so I have posted this on a different platform where you can comment. I invite you to comment here.

References

Gray, P. (2011). The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. American Journal of Play, 3, 443-463.

Gray, P., Lancy, D.F., & Bjorklund, D.F. (2023). Decline in independent activity as a cause of decline in children’s mental wellbeing: summary of the evidence. Journal of Pediatrics 260, 1-8. 2023. Available here.

Kovess-Masfety, V., et al (2016) Is time spent playing video games associated with mental health, cognitive and social skills in young children? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51, 49-357.

McCain, J.A. (2009). Antidepressants and Suicide in Adolescents and Adults A Public Health Experiment with Unintended Consequences? Pharmacy and therapeutics, 34, 355-378.

Olson, C. K. (2010). Children’s motivation for video game play in the context of normal development. Review of General Psychology, 14, 180-187

Przybylski, A. K., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology, 14, 154-166.