Career

Is My Job Still a Good Fit?

Two simple lists can help you decide whether to stay or leave.

Posted March 30, 2019

In my last post, I introduced the value of deceptively simple career-enhancing lists: a method for getting your career ideas out of your head and onto paper so that you can organize them, reduce the clutter in your mind, and stop feeling overwhelmed. In this post, we’re going to look at a list technique that dates back to the 1950s, but is still relevant today, as well as a modern variation of that list. What I particularly like about these two lists is that you can use them any time during your career — not just when you’re seeking a new job. Completing and comparing the information you put on these two lists can help you determine whether or not your job is as good a fit as you think it is.

Keep in mind my suggestions from the previous post: You don’t have to number your list, particularly if you’re going to be influenced by the number. The best idea on your list isn’t always the first item you write down; it might be item #25, so don’t worry about the order in which you write your responses. And yes, it’s a good idea to list all your ideas, not just the first few that pop into your mind. Take the time to fill your list out fully, and even go back to it later to add more ideas as they appear.

You will uncover information about yourself that may surprise you as you complete these lists, so consider sharing your responses with a friend, counselor, coach, or psychologist. We often don’t see ourselves as others do, and getting feedback can help you talk through what you uncovered, possibly developing even greater insight, as well as new ideas for future plans.

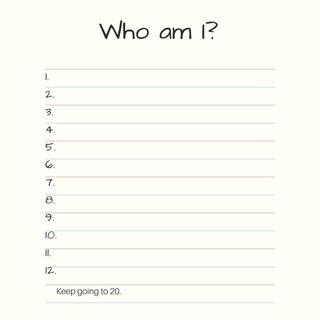

So let’s try the first list:

Who Am I?

“Make a list of what is really important to you. Embody it." —Jon Kabat-Zinn

The search for “Who Am I?” lasts a lifetime and changes over time. That’s why this list can be so powerful. Psychologists began asking clients to complete this list at least as early as the mid-1950s, and it has been found to be a powerful means of self-exploration. Two researchers, Kuhn and McPartland (1954), called it the “Twenty Statements Test,” and they found that most people describe themselves in two ways: either in their social roles (son, daughter, mother, father, etc.) or through various traits (smart, funny, extroverted, etc.). What is most interesting is the way you choose to describe yourself. Try it now.

Look for patterns in your list. Do you notice that you focus on certain personality traits? Are they a source of pride or pleasure? How could you use those traits to develop stories for a job interview?

What roles did you list? Try expanding on those roles by listing what traits or characteristics you exhibit in those roles.

Did you list traits that you’d rather not acknowledge about yourself? Consider whether they are aspects of your personality you can change — or want to change. If so, this list might be a great resource to bring to an appointment with a counselor or psychologist to help you determine what can be changed and what needs to be accommodated or mitigated.

One of the things you might have noticed about your “Who Am I?” list is that you might behave differently in different settings. In your role at work, you might take on or use specific traits that you wouldn’t use at home. Your job might require you to be different — perhaps more organized or more efficient.

That's why completing this next list is important. The following exercise can help you uncover those differences.

Who Am I at Work?

Let’s try a variation on the “Who Am I” list, which is suggested in a Fast Company blog post by Dr. Art Markman at The University of Texas at Austin. Create your new list, this time focusing only on your traits and behaviors at work.

What did you discover? Compare your two lists. Did you find traits you exhibit at work that you didn't list on your “Who Am I?” list? Are those traits generally more positive or negative? For instance, do you find that you are more efficient or organized at work than you would normally describe yourself?

Or do you find that you are more stressed or anxious at work than you would normally describe yourself?

These may be important clues to changes you need to make at work, or characteristics you possess that you will want to incorporate into your non-work life.

Consider expanding the comments you wrote on your list. For instance, if you wrote that you were “stressed” at work, take a moment to jot down what situations cause you to feel stressed. Is it your workload, supervisor, co-workers, etc.? Are you under tight deadlines or constant pressure? Are you in a high customer service role where you are always being rated or evaluated — potentially online? All those factors can lead to a self-description of “stress.” Isolating your reasons for feeling stress can start you moving forward on a possible solution.

You might find that your current job works perfectly for your personality. You like lots of action, last-minute decision-making, and an opportunity to demonstrate your skills — and your job lets you do that. So if you need to make changes in your work for some reason (say a required move due to family concerns), you know that you should seek the same job in the new location, or a job which has similar characteristics.

You can also use to list to determine if your job requires you to “work against type,” which might explain why you come home tired every evening. Working against your natural type might also make you more susceptible to burnout.

By completing these two lists, you now have a picture of who you are at the present time, both in work and non-work settings. The advantage of writing these lists is you can clearly see what parts of your life are working and what parts might need to change. You can consider how serious any differences are. You might be perfectly OK with the different roles you take on between work and home, or you might find the gap or dissonance too strong. Depending on how you feel about these two lists, you can take action as needed.

You can use the information to stay in your same role (even when other offers are coming your way). You can use your new knowledge to create stories and examples of your strengths during interviews or promotional pitches. In his Fast Company article, Dr. Markman recommends you use the information to write a better LinkedIn profile.

Bottom line: Having this concrete knowledge about the fit between your personality and traits and your job can help you make some (possibly hard) decisions about whether to remain in your current job or seek something new.

© 2019, Katharine S. Brooks. All rights reserved.

References

Kuhn, M., & McPartland, T. (1954). An Empirical Investigation of Self-Attitudes. American Sociological Review, 19(1), 68-76. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2088175