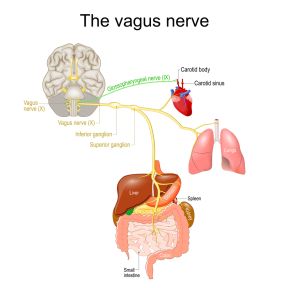

Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve, the longest nerve in the body, originates in the brainstem and extends down into the abdomen. It monitors and receives information about the functioning of the heart, lungs, and other internal organs so that you can focus attention on other matters.

It is the duty of the vagus nerve to orchestrate bodily responses to keep you safe or warn you about danger before you even have a chance to think about it. Without your awareness, the brain scans the environment for cues of danger, pitching you into high alert to fight or flee or, in extreme situations, shutting you down. It also scans for cues of safety, which allow you enough calm to open you up to socially engage with others.

Contents

Vagus means wandering, and the vagus nerve, after it leaves the base of the brain, sends branches to the ears, the throat, the heart, the lungs, and the digestive tract, with stops along the way at the vocal cords and the diaphragm, before descending into the abdomen. The branches of the vagus nerve enable the organs to adjust instantly to the demands of a person’s internal and external environment.

The vagus nerve is why your heart races and stomach curdles when you sense a threat and why your breathing slows and your body relaxes when friends welcome you to their house. The vagus nerve is the key player in the autonomic nervous system controlling your internal organs.

The vagus nerve is a major pathway of the parasympathetic nervous system, which, along with the sympathetic nervous system, constitutes the autonomic nervous system. Normally, sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves act synergistically and together create the state of equilibrium known as homeostasis. Disruption of the balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity is characteristic of a number of physical disorders with a strong psychological component—irritable bowel syndrome, for example—and some therapies target stimulation of the vagus nerve as a way to restore physiologic, and psychologic, balance.

Containing both sensory and motor fibers, the vagus nerve is in charge of both sensations and movement. Through its many branches, it controls swallowing and speech. It carries the sense of taste and sensations felt by the ears. It is responsible for involuntary muscle and gland control of the viscera, encompassing the heart, the lungs, the esophagus, and the rest of the digestive tract. It controls breathing and heart function, including heart rate. It relays sensations originating in the cervix and other organs of the abdomen.

Because information flows both to and from the brain via vagal pathways, the vagus nerve can be thought of as a major mind-body highway. The many branches of the vagus nerve are increasingly seen as pathways for promoting or restoring health and ameliorating the physiologic unease that gives rise to anxiety and other negative mental states.

States of visceral calm get relayed up to the brainstem, which then transmits the information to more highly evolved brain structures, allowing full access to the brain’s means of expression and enabling social interaction—which has the effect of perpetuating the state of neural calm. But in potential danger states, such as completely novel environments, those higher systems turn off and we become defensive and on high alert: The vagal circuitry narrows our focus and prepares us to fight or flee—the so-called stress response.

If the danger is so overwhelming that there’s no escape or there’s a feeling of being trapped, a third circuit of vagal operations engineers a shutdown. In this out-of-focus, numb state, social contact becomes aversive. Such bodily responses are not voluntary, and often people are not aware of what triggered them, although they are likely aware that their heart is pounding or their body is trembling.

Because the vagus nerve operates bidirectionally, states of homeostasis and calm, which are necessary for restoration and growth, can be induced from the bottom up or the top down. That is, the brain can deploy cognitive and other strategies to dissipate states of bodily unease (top down), or it can activate the vagus nerve at a number of points in its path to create psychological comfort and a sense of safety (bottom up).

Defense is a major obligation of every living system, and humans are no different. It is the job of the autonomic nervous system to detect danger and keep us safe. Before we are even consciously aware of it, the autonomic nervous system detects threats and responds, enacting a defense strategy to help us survive. Activation of the stress response, setting off a cascade of physiologic changes to prepare the body for fast action if needed, is a hallmark of the strategy. So is an outpouring of signaling chemicals and pro-inflammatory compounds that circulate through the body, including the brain. Anxiety is the name we give to the visceral unease we feel under such conditions.

Many of the chemical changes stirred by the detection of threat act directly on the brain, jolting it into alertness, sharpening senses, prompting a search for something amiss—even setting off a sense of doom—and shutting down such higher brain functions such as decision-making and creativity. Heart rate, breathing, blood pressure, all go into high gear, readying the body for movement. The shifts in physiologic state in response to threat are kicked off by the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system.

By contrast, the vagus nerve, the main component of the parasympathetic branch of the nervous system, is the architect of safety. It acts to down-regulates the response to threat, to restore visceral order and psychological calm. Its action is needed to enable renewal and growth. And in shutting down defenses, it sets the psychological stage for social interaction.

The vagus nerve connects the brain with the major organ systems of the body. It links mental and physical processes. It is the means by which the mind and body are physiologically inseparable; signals that affect one directly affect the other, although they find expression in different ways.

Among the many operations of the body and brain it controls, the vagus nerve is responsible for relaxing tension, counteracting activity of the sympathetic nerves and establishing the very positive state of homeostasis, sometimes called “rest and digest.” It down-regulates the response to stress, curbing the physiologic state of alarm and ushering in a state of calm experienced as a sense of safety, which the body needs for repair, growth, and reproduction. The disturbed physiology that marks states of threat is often a player—sometimes an unrecognized one—in chronic physical and psychiatric disorders, giving the vagus nerve a huge role in maintaining health in the body and the brain.

The vagus nerve oversees digestion and is one of the main channels of connection between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract. Among many other actions, it ferries to the brain signals generated by the metabolic actions of the gut bacteria on specific types of food—one means by which diet plays an important role in mental health. The vagus nerve also conveys signals of other neuroactive substances secreted by the digestive tract; among the best known are those that control appetite. The vagus nerve also contributes to the immune defense of the gut.

Through its huge role in stress and its relief, the vagus nerve influences inflammation. The stress response to threat is accompanied by activation of the immune system; the body begins turning out pro-inflammatory compounds such as cytokines. If the stress is prolonged, the cytokines can inflict significant damage on organ systems. In addition, chronic and acute stress can break down the lining of the gut and pave the way for toxins to enter the bloodstream, activating the immune system and setting the stage for inflammation.

Detecting threat is a basic survival function, and humans respond to the detection of threat with a sweeping set of physiologic changes set in motion by the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. It initiates a signaling cascade that alerts and activates the entire system and unites the brain and body in a common goal of survival. It makes no difference what the source of the threat is—a virus, a tiger, a bad boss, discrimination, abuse, a bad memory— the body responds the same way, activating many organ systems, turning up alertness in the brain, turning off high-powered cognitive and executive functions (they consume energy needed for potentially lifesaving physical action) and our capacity for social connection, creating negative expectations, and generally establishing a sense of unease.

States of threat are not sustainable long-term—we literally fall apart mentally and physically. Our built-in balancing mechanism is the vagus nerve. Once an immediate danger is past, the vagus nerve must act to establish a physiologic state of calm, which is reflected in a sense of safety. The level of safety we experience determines our ability to recover and heal and our level of wellness and health.

Activation of the immune system, along with the stress response, is one of the first-line defenses in response to threat. The result is a state of inflammation. Inflammation, however, sensitizes the brain and revs up the speed of nerve conduction; the result is that people feel more pain more intensely.

It’s important to recognize that pain is a necessary piece of sensory information—it alerts the nervous system to direct behavior so as to avert permanent damage. In the presence of persistent threat, however, pain can become chronic. Over time, the physiologic changes induced by stress create wear and tear on body systems, leading to damage and creating more sources of pain.

The vagus nerve is a conduit of the sensory information from the viscera to the brain. But it can also be activated to mitigate chronic pain. Stimulating the vagus nerve can influence the pain of migraine and arthritis, as well as subdue many sources of visceral pain. It is considered a promising add-on treatment for inflammatory bowel disease.

The vagus nerve monitors and regulates heart rhythms and is responsible for the fluctuations in heart rate to meet the routine and unplanned demands that are part of everyday life. Vagal tone is a term that describes the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) activity, and it is assessed by measuring heart rate variability—the ability of the heart to respond to situations that demand an increase or decrease in blood flow and thus a faster or slower heart rate. Using an electrocardiogram, clinicians time beat to beat variation, measured in milliseconds.

Good vagal tone means that the heart can react quickly to increase cardiac output—and to increase rate of breathing, to oxygenate all that blood—in the presence of danger and can ramp down after the experience of stress. Stimulating the vagus nerve mechanically is used therapeutically to control a number of cardiac arrhythmias.

Heart rate variability, reflecting a balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) activity in the body, is considered an indicator of both physiological and behavioral adaptability and resilience and a reliable marker of general health. Low vagal tone is not only a marker of cardiovascular risk but is seen in functional disorders of the digestive tract and inflammatory bowel disease, in other inflammatory conditions, and with psychopathology. Heart rate variability, studies show, is linked to the capacity for emotion regulation.

The vagus nerve controls the movement of the vocal cords. It prompts one set of muscles to open up the voice box to allow us to breathe and another set to close it to allow us to talk—and another that enables us to change pitch and sing. As many professional singers know, vagal tone can influence the condition of the voice, induce hoarseness, and even, sometimes, vocal cord paralysis.

By the same token, the voice can be used as a means of increasing vagal tone. Making sounds with certain frequencies of vibration—humming, singing, even gargling—all stimulate the vagus nerve. Singing has been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Neuroscientist Stephen Porges developed the polyvagal theory from his decades-long study of the vagus nerve and deciphering the daunting complexities of its operations. He argues that stress responses can be regulated due to the interconnectedness of body reactivity, cognitive and emotional function, and social behavior. Through the vagus nerve, we react to signals in our environment in ways that calm, alarm, or dysregulate the body, and these states in turn create emotional experience and play out in behavior.

As a large neural pathway between much of the body and the brain, the vagus nerve operates automatically to control many functions. It is also susceptible to influence in multiple ways.

Breathing. Heart rate. Blood pressure. Digestive functions including movement of food through the gut. All are controlled by the vagus nerve.

Vagal tone is a term often used to indicate the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) activity in relation to the heart, and it is assessed by measuring the heart’s ability to respond appropriately to situations that demand an increase or decrease in cardiac output and thus a faster or slower heart rate (heart rate variability). Good vagal tone allows the system to ramp up quickly as conditions demand (say, a sudden need to flee a dangerous situation) and to settle down after an experience of stress. Low vagal tone is a feature of inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and other disorders of the gastrointestinal tract.

As the autobahn of mind-body interaction, the vagus nerve is a powerful modulator of mood, a major pathway of the stress response, and a participant in conditions as diverse as heart disease and vocal paralysis. The feeling of anxiety—the mental state of modern times— is a reflection of the agitated physiologic state created by threat and relayed to the brainstem via the autonomic nervous system. As it is interpreted by higher brain structures, the physiologic turmoil turns on a suite of negative emotions. Through the use of higher brain structures—memory, previous learning, networks of associations—people create narratives of worry to explain the visceral unease. Thoughts focus on problems and other bad things. People create catastrophic “what if…” scenarios having a whole range of negative outcomes. There may be a feeling of impending doom.

In the panoply of negativity turned on by the physiologic unease, people also develop negative feelings and beliefs about themselves. Researchers have documented that worriers display themes of personal inadequacy and low self-esteem. They believe that they lack control over events. And they lose confidence in their ability to solve problems. Responding to unease with worry sets off a downward spiral of distress from which it is often difficult to escape.

Mechanical activation of the vagus nerve, in which an implanted device delivers intermittent impulses to the vagus nerve, is currently used as a treatment of resistant depression. But there are many other ways to stimulate the vagus nerve noninvasively to restore mental health.

Increasingly, scientists are coming to understand the connections between physiologic and psychologic states of distress, with their accompanying sense of threat, on the one hand, and states of physiologic and psychologic calm, with their accompanying sense of safety, on the other. As a result, the vagus nerve has come into sharp focus as providing effective, noninvasive ways of restoring physiologic and psychologic composure. As the commander-in-chief of the parasympathetic nervous system, the vagus nerve countervails systemic unease and the "fight-or-flight" stress responses to induce a state of calm and restore homeostasis.

It’s not just enough to remove the threat; the nervous system demands cues of safety. Through the application of specific maneuvers stimulating vagal pathways, the nervous system can be used to reset physiologic state. Shifting physiologic state restores access to all the higher cognitive capacities including memory and restores the capacity for social engagement.

Stimulation of the vagus nerve is medically well known as a means of regulating the excitability of nerve cells. It is currently used therapeutically to normalize heart rate in people subject to certain cardiac arrhythmias and to control refractory epileptic seizures. It is also sometimes used to treat resistant depression; imaging studies indicate it curbs overactivity of certain regions of the brain. Such treatment involves the use of a device—either implanted inside the chest cavity or noninvasively affixed to the skin— that delivers intermittent electrical impulses to the vagus nerve. There are, however, many simpler maneuvers (see How to stimulate the vagus nerve) that almost anyone can do to activate the vagus nerve and modulate vagal tone.

When the body is in states of danger or even in complete shutdown, it is possible to restore calm and regain behavioral flexibility by redirecting vagal activity, which can be accomplished through a deceptively simple maneuver—breathing. Specifically, the effect requires breathing deeply and exhaling slowly, ideally so that the exhalation lasts twice as long as the inhalation.

By engaging the diaphragm, deep-breathing activates vagal pathways that counteract both the flight-or-fight stress response and behavioral shutdown. Most people respond to the experience or even the anticipation of stress in any form by stopping breathing and holding their breath. Breath-holding itself activates the fight/flight/freeze response; it also increases the sensation of pain, stiffness, anxiety, or fear.

Deep breathing allows people to feel “centered.” Such vagal breathing not only lowers defenses, relaxes the body, and slows heart rate but also gives people access to their higher mental powers; studies show that, among other things, it improves decision-making. The deep breathing can be done anytime, anywhere, to foster relaxation.

In diaphragmatic breathing, the belly expands and rises as the lungs fill with air. The movement of the diaphragm stimulates the calming circuit of the vagal nerve. Deep, slow breathing that moves the diaphragm is an integral part of many ancient meditation traditions. Yoga long ago incorporated the power of respiration—bellows breath is one exercise—to change physical and mental states. The ancients knew that it worked; they just didn’t know how it did.

As the primary pathway connecting the brain and the gut, the vagus nerve is an obvious route for inducing calm in the gastrointestinal tract. Further, in its direct connection to the gut, the vagus plays a role in hunger and satiety. And because it transmits the psychoactive products of digestion to the brain, it can, in the presence of a bad diet, literally feed psychiatric disorders. If that isn’t enough, the vagus also regulates inflammation in the gut and throughout the body. Modulating vagus activity through stimulation of the nerve in meditation practices has already proved to have therapeutic effects.

Depression is associated with overreactivity of the stress response and the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA). It is also linked to elevated levels of inflammatory compounds. Stimulation of the vagus nerve is believed to tame overdrive of the HPA and, through multiple pathways, including curbing the stress response, reduce production of proinflammatory cytokines. The breathing techniques of many meditation practices and postural changes involved in yoga exercises all have measurable effects on vagal tone and are often incorporated into depression treatments. In epilepsy, direct electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve reduces the hyperexcitability of brain cells, reducing seizure activity.

The implantation of devices delivering electrical signals is by no means the only way to activate the vagus nerve. Many noninvasive actions—dipping the face in ice water is one of them, and it has long been used medically—can activate the nerve at points along its winding pathway from brain to abdomen.

• Take long, deep breaths

Deep, slow breathing that moves the diaphragm—with exhalations twice as long as inhalations—activates the vagus nerve to restore a sense of calm. Many traditional meditation practices incorporate some form of breath control for this reason, and cognitive behavioral therapies typically have a breathing component.

Most techniques advise breathing in slowly—ideally to a count of 10—through the nose so that the stomach moves out (placing a hand on your stomach can be a helpful guide). The extended, slow inhalation is followed by an even more extended, complete exhalation through pursed lips. Repeating the process five or 10 times is advised.

• Engage "vagal maneuvers"

Cardiac patients who are subject to the arrhythmia known as tachycardia—a racing heart—are often taught “vagal maneuvers” as a way to try to slow the heart when the rhythm is out of control. All stimulate the vagus nerve in one way or another. Classic vagal maneuvers include bearing down, as in making an effortful bowel movement. The stomach expansion activates the vagus nerve.

Another classic vagal maneuver is dipping one’s face in ice water or putting a plastic bag filled with ice water on the face—it engages the so-called diving reflex. The cold stimulates the vagus nerve. Yet another is coughing, which activates other branches of the vagus.

• Sing loudly, or hum

Because the vagus nerve serves the vocal cords, it can be stimulated by making emphatic sounds. Singing works. Singing with others works even better. Regularly singing with a chorus stimulates the vagus nerve by both physical and social routes.

• Gargle

Gargling requires that you contract the muscles at the back of the throat, which are fed by the vagus nerve. When you gargle the muscles close the throat, which activates the vagus nerve .

• Dance

Moving the body in any way is a very effective means of activating the vagus nerve. Its neural pathways are involved in posture and balance—and dance is nothing if not an esthetically (and emotionally) pleasing way of constantly shifting posture while maintaining balance.

Stimulating the vagus nerve helps restore calm and allows access to problem-solving, creativity, and other higher brain functions whenever a person feels anxious, lost in uncertainty, or out of control. Deep breathing can ground a person in the middle of a panic attack and restore a sense of control. It is useful for slowing a racing heart. And it is an effective means of lowering blood pressure. It can be done silently, invisibly almost anywhere, any time.

Stimulating the vagus nerve by deep breathing is a component of most cognitive therapies for depression and anxiety and is considered an important treatment strategy. Calming techniques such as deep breathing prepare patients to fully participate in and benefit from the cognitive and emotional work of the therapeutic process.