Neuroscience

Do We Really Need A Brain?

Tales that keep neuroscientests up at night.

Posted March 26, 2013

I want to discuss something that is terrifying to neuroscientists like myself. It may be the most forbidden question in my field, but someone has to ask it.

What if our brain isn't really necessary for our behavior at all?

This is the scary campfire story that we tell young graduate students to keep them up at night (and in the lab). We don't need bloody hooks and mirrors... just the thought that perhaps everything we are studying is premised on a faulty assumption that the brain gives rise to behavior.

Sound crazy? Far fetched? Impossible?

Well, you're probably right. But there are surreal anecdotal stories that sometimes give us pause and question our assumptions of what we think we know about the organ sandwiched between our ears.

Let's consider some extreme and strange cases shall we?

Warning: The following might be a bit graphic for those readers who were prone to fainting in biology class. Proceed at your own risk.

Attack of the Headless Rooster

Meet Mike. Mike was a chicken with a very unfortunate story. You see, one day Mike was set to become someone's dinner, as many a fowl are. With his head on the chopping block (literally) Mike's fate was left to the accuracy of a farmer's axe.

Mike the Headless Chicken

Fortunately (or unfortunately) for Mike, this particular executioner had bad aim. So while most of his head was cleaved clean off, his brainstem was left intact. After his attempted execution, Mike simply stood up and walked around like nothing had happened.

"Big deal!" you might say, "We all know that chickens will run around for a little while with their heads off, hence the popular phrase."

Here's where things get weird. Mike didn't just run around for a few seconds and then succumb to his fate. No, Mike continued to walk around and live life as a headless rooster for the next eighteen months!

Ichabod Crane had nothing on this bird.

Mike's owner took him on the road to show off the famous headless fowl. Through a delicate and somewhat grotesque feeding ritual, Mike remained alive for well over a year. He exhibited all the normal chicken behaviors (well all the behaviors a chicken can do without his head), until the day he finally made it to the kitchen table.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves here (zing!), it seems obvious that relatively simple creatures like chickens, with smaller and less complex brains than our own, might not need much gray matter to function. Yet surely to live the life of a human, you need a substantial amount of neural tissue.

Right?

"I'm sorry to tell you, but you've been living without a brain for the last 40 years."

Imagine that you are a neuroradiologist looking at MRI scans of brains. You’re drinking your vanilla mocha frappuccino and flipping through images, making diagnoses. A tumor here, a stroke there, a normal brain here, encephalitis there.

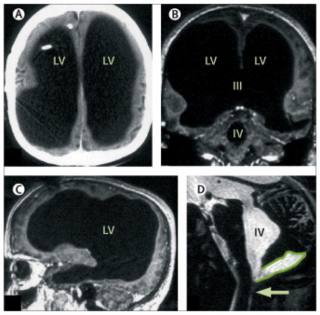

Suddenly you come across a scan showing a giant hole where 75% of the brain should be. Mostly black space where important brain parts normally are.

The brain image of a perfectly normal middle class fellow.

You'd think to yourself, "Surely this has to be someone in a sever coma who will never wake up again."

This brain, in fact, belongs to a well adjusted and, more importantly, conscious man who to this day enjoys a comfortable middle class life.

Despite having dramatically enlarged ventricles (reservoirs of liquid that act as the sewer system of the brain) that squished out most of his normal neural tissue when he was young, this gentleman somehow managed to grow up normally, get an education, a middle class job, a wife and kids.

All of these seemingly normal accomplishments while having less than half of the brain volume that you or I might have in our skulls.

Although at this point who knows. We should get our heads scanned just to check.

So do we really need a brain?

Do these anecdotal stories mean that we should throw out the entire theory that the brain gives rise to behavior?

Hell no. Not even close.

But this does tell us that we may have to rethink our assumptions about what it means to be "brain damaged." When we see a mangled and severely injured brain of someone in a coma, perhaps we should think twice when we assume that all of their cognitive abilities have gone away forever.

Indeed, many new neuroimaging studies are suggesting just that. By showing voluntary neural responses to questions in comatose patients, scientists are opening the door to communicating with individuals once thought to be beyond hope.

The brain is a beautiful organ that is astoundingly resilient to change. It can learn. It can adapt to damage. Sometimes it’s a good idea to just take a step back and appreciate this from time to time.