Relationships

Needs, Conflicts, and Resolutions

What couples want from partners during conflict.

Posted October 4, 2013

What is the fundamental need that you have in your relationship with your partner? And, if that need feels threatened, what are the core themes that are likely to emerge, especially during a conflict? Given core concern, what, then, would result in a better or worse resolution?

Let’s start with an example to frame these questions. Early in my marriage, these factors occasionally played out in a way that might be described as neurotic. As a young adult, I had some insecurity about my desirability that stemmed from some unfortunate failed attempts at dating in high school. One of the needs I had in my relationship with my wife was the need to be desired. Interestingly, I was not really aware of this need. Basically, I was defended against this need because I knew my wife loved me and I had high self-esteem and would have thought it weak to acknowledge such a need. But because I denied it, it played itself out in a less than fully adaptive way. For example, sometimes when we were in conflict or when I was feeling stressed or insecure, I would pull away from my wife and give her the cold shoulder. Subsequent couple’s therapy helped me verbalize both to myself and my wife that actually the cold shoulder was a test. My subconscious desire/fantasy was that, despite my slight rebuff, my wife would still desire me, push through my resistance and insist on “connecting”. If that happened it would have affirmed my need. I know it will be a surprise to all to hear that the cold shoulder generally did not result in my desired outcome of being more desirable. That was why we were in therapy, which I am happy to say quickly resolved the issue via insight and clear communication. As a clinician, I can say with confidence that I am not the only one whose subconscious desires and core concerns have resulted in neurotic tests and games with one’s partner, usually with maladaptive outcomes.

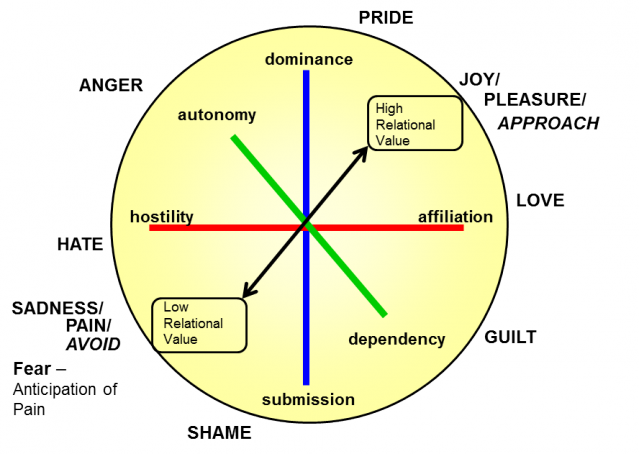

Let’s now introduce some concepts to get a clear framing of the issues at hand. The map of the human relationship system provided by the Influence Matrix suggests that the central dynamic in intimate relationships is the degree of experienced relational value, which is the extent to which one feels known and valued by important others. Through this lens, attachment theory relates very much to the extent to which infants and children feel valued by their parents, which then leads to an emotional sense of comfort and security (or not). The Matrix suggests the same basic concern is present in our romantic relationships. Emotionally, we crave to be known and valued by our significant others.

Although not working directly from the perspective of the Influence Matrix, Keith Sanford at Baylor University has started to research a perspective on couples that is very much in tune with this basic thesis. He argues, based on an evolutionary logic similar to that embedded in the Matrix, that people are primed by evolutionary pressures to be attuned to what he calls “underlying concerns”. An underlying concern is the person’s primary or core reason for feeling distressed during a relational conflict. Sanford and colleagues argue that there are two primary kinds of concerns, perceived threat, which relates to the partner being controlling, demanding, power-driven, or critical, and perceived neglect, which relates to the concern that the partner will not invest or show love, sexual attention, or approval. Sanford developed an instrument of underlying concerns and found a robust, two factor structure, one representing perceived threat (e.g., “I felt blamed”, “My partner seemed demanding”), the other corresponded to neglect or not being desired (e.g., “I felt neglected”, “My partner seemed uncommitted”). Of course, both of these kinds of concerns relate directly to the experience of relational value. I am devalued to the extent my partner controls me, blames me, and makes me feel inferior or unworthy. I am also devalued to the extent that my partner rejects me, neglects me, or invests in others over me. Importantly, these are exactly the kinds of themes that would be predicted by the Influence Matrix, as the two dimensions of underlying concern relate directly to the vertical (power) and horizontal (love) dimensions of the Influence Matrix.

What are some practical applications and implications of this model? To start, the idea of underlying concerns gives rise to a framework for the kinds of desired resolutions that individuals might want from their partner in response to a conflict. Indeed, this was the focus of Sanford and colleagues latest work. In two studies, published in the June 2013 issue of the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, they explored both the kinds of underlying concerns individuals had regarding their partner and examined the kinds of desired resolutions that would be most helpful or fulfilling. The authors identified 28 categories of desired responses which were then grouped into six categories (Stop being adversarial, relinquish power, show investment, communicate more, give affection, and apologize). Showing the basic validity of the formulation, the researchers found that those with underlying concerns of perceived threat had desired resolutions that involved the partner stopping being adversarial and/or relinquishing power, whereas those whose concerns related to neglect desired a show of investment and/or giving affection.

Arguably the most important development in couples work over the last decade has been the growing realization that core concerns about relational value exist at the heart of most couple difficulty. Emotion focused therapy for couples examines emotionally charged exchanges through the lens that ultimately partners are communicating needs for love, respect, and being valued. The therapy helps couples realize the nature of that dance and to create a relational holding environment where needs can be authentically expressed and responded to. For example, consider how much more positively my wife responded to, “I sometimes feel insecure and that activates a concern in me that you don’t desire me as much as I need you to”, compared with the perplexing cold shoulder out of the blue.

Sanford’s empirical work adds the importance of identifying the kinds of relational value concerns that are likely to be most central (i.e., threat or neglect) and thus provides couples a potential pathway toward understanding the kinds of resolution acts that are likely to be most helpful in resolving a conflict or repairing emotional insecurities that follow (relinquish power or show more investment). I, for example, had little concern about perceived threat. Indeed, my concerns were fairly well localized around a particular aspect of perceived neglect, affectionate desire. As such, this is a good example of how a scientific analysis of relationship patterns can inform clinical work in the real world.

_______________

Reference

Sanford, K. & Wolfe, K. L. (2013). What married couples want from each other during conflicts: An investigation of underlying concerns. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 32, pp. 674-699.