Creativity

The Art of Positive Skepticism

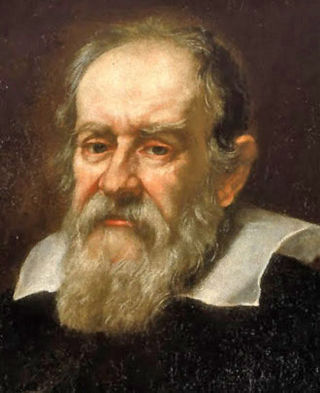

Five ways to think like Galileo and Steve Jobs.

Posted June 5, 2012

In the late 1500’s, everyone believed Aristotle’s claim that heavy objects fell faster than light ones. That is, everyone except Galileo. To test Aristotle’s claim, Galileo dropped two balls of differing weights from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. And guess what? They both hit the ground at the same time! For challenging Aristotle’s authority, Galileo was fired from his job. But for his place in history, he showed us that testing human claims should be the mediator of all truth.

Fast forward to modern times. Challenging commonly held assumptions about computers and human behavior, Steve Jobs lost his job with Apple in 1985. Returning 12 years later, he changed the way people use technology by testing the truth of other people’s claims. As a result, history considers Jobs one of the most innovative minds of the 21st century.

Galileo and Jobs were skeptics. They had developed habits of thinking that challenged what appeared to be reliable facts. They understood that testing assumptions over human authority led to greater understanding, innovation, and creativity.

It’s easy to confuse being a skeptic with being a cynic. So let’s define the terms.

A cynic distrusts most information they see or hear, particularly when it challenges their own belief system. Most often, cynics hold views that cannot be changed by contrary evidence. Thus, they often become intolerant of other people’s ideas. It’s not difficult to find cynics everywhere in our society, from the halls of Congress to our own family dinner tables. People who are driven by inflexible beliefs rarely think like Galileo or Jobs.

Skepticism, on the other hand, is a key part of critical thinking – a goal of education. The term skeptic is derived from the Greek skeptikos, meaning “to inquire” or “look around.” Skeptics requires additional evidence before accepting someone’s claims as true. They are willing to challenge the status quo with open-minded, deep questioning of authority.

In today’s complex world, skeptics and cynics are often hard to differentiate. While the ability to challenge human authority has led to important innovation and reform, it has also made it possible, for a price, to prove our “rightness.” Oftentimes, what appear to be legitimate studies are manipulated to support a particular idea or outcome that a company, individual, or government believes is the truth.

And herein lays the dilemma of our modern day quest for certainty. When we can no longer be objective “inquirers” because we have already decided the truth, then we create a culture of cynicism instead of skepticism. Is this the kind of world we want for ourselves and our children?

If we model skepticism instead of cynicism, our children would inherit a world that would be less dependent on power and authority and more dependent on critical thinking and good judgment. Adolescents and young adults would be capable of questioning the reliability of what they think or hear. They would learn to believe in their natural abilities to facilitate positive change through intellectual inquiry. They would become discerning consumers of ideas rather than passive accepters of other people’s visions of certainty.

How we adults model the art of positive skepticism not only helps us make better informed decisions but also shows our children how to think for themselves. And, if kids learn to think for themselves, they learn to believe in themselves!

Five Ways to Model Positive Skepticism

Be a Deception-Detector

People constantly make claims that affect our daily lives. From those selling products and services to candidates running for political offices, we are barraged with decisions that require us to act. Thomas Kida, in his book Don’t Believe Everything You Think, shows how easily we can be fooled and why we should learn to think like a scientist.

Challenge claims by asking for evidence. Ask questions like, “What makes you think this way?” “What assumptions have you based your claim upon?” “What facts or research support your ideas?” “Are there facts or studies that dispute your claim?”

Doubt

Constant streams of commercial messages, TV news, and campaign ads try to tell us how to think. When we allow others to think for us, we become vulnerable to indoctrination, propaganda, and powerful emotional appeals. In her book, Descartes’s Method of Doubt, Janet Broughton examined the important role that doubt plays in our quest for truth.

Recognize the limits to anyone’s claims of truth! Look below the surface rather than accepting ideas at face value. Ask yourself questions like, “What is the logic of this argument?” Listen to yourself when something doesn’t feel right!

Play Devil’s Advocate

Part of being a good skeptic is learning to play a devil’s advocate role. Take a position you don’t necessarily agree with, just for the sake of argument. This doesn’t have to be combative. You can simply say “In order to understand this idea better; let me play the devil’s advocate.” Putting your mind to work poking holes in what you think might be a good idea can lead to greater understanding of a problem. Playing devil’s advocate is a great way to teach children how to see another person’s perspective.

Use Logic and Intuition

We are persuaded to doubt or believe other people’s claims through logic and intuition, and most of us tend to rely heavily on one type of thinking or the other. Whether you are a logical or intuitive thinker, it’s helpful to alternate between these two qualities of mind. In his book, Embracing Contraries, Peter Elbow says, “Doubting and believing are among the most powerful root acts we can perform with our minds.” We become better thinkers when we deploy doubting and believing more consciously through the use of logic and intuition rather than by chance.

Be a Bias-Detector

One of the most important tasks of a true skeptic is to determine whether sources of information and analysis are impartial. This is a trait that serves us well when we turn on the television. If we only listen to one channel, or our favorite news commentator, we’ll likely be persuaded by biased or emotional appeals. Ask yourself, “What’s the other side of this story?” “Is this one person’s story or does it apply to thousands of people?" “Is there an underlying belief or assumption being made that reflects this reporter’s ideology?”

R.M. Dawes’ points out in his book, Everyday Irrationality: How Pseudo-Scientists, Lunatics, and the Rest of Us Systematically Fail to Think Rationally, that emotional appeals and story-based thinking often lead to faulty reasoning. The point in detecting bias is to be able to identify messages that are intended to persuade rather than inform us.

Positive skepticism leads to better problem-solving, innovation, and creativity! It also helps develop our abilities to think critically about the world around us! Do you agree? Feel free to poke some holes in my thinking!

Marilyn Price-Mitchell, PhD, is a developmental psychologist working at the intersection of youth development, leadership, education, and civic engagement.

Subscribe to Updates at Roots of Action to receive email notices of Marilyn’s articles.

Follow Marilyn at Roots of Action, Twitter, or Facebook.

Photo Credit: Thoilmas Lieser; David Goehring

©2012 Marilyn Price-Mitchell. All rights reserved. Please contact for permission to reprint.