Ethics and Morality

Greed & Secret Lives – Part II

Good Greed can Turn into Bad Greed - Watch Out!

Posted July 30, 2012

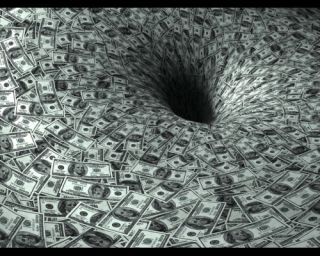

Money is very powerful and can affect us all.

Like sex or hunger, the appetite for money can get us to do things we may later regret. This is true for you and me; it is also true (and maybe more so) for those in the banking and finance industries.

Do you notice how you may gamble more than you should, or cheat here and there, thinking that everyone does it? Or, maybe you think that "I won't get caught" or, "it's just this time." Watch out, because greed often makes otherwise good people make bad mistakes. With your next door neighbor's financial secret lives in mind, I thought it might be useful to present a series on the psychology of banking misbehavior. When a finacial giant fudges or steals, it's big. And, it shows how the mind is affected by the power of money.

------------------

Many of us know great people in the finance industry, and yet we hear too much bad news; and often at very high levels.

What gives?

Since I am of the Hebraic tradition, I don’t often quote that great Rabbi from the Galilee. But, here he makes a point for the ages; that people don’t often know our own minds.

“Father, forgive them, for they do know not what they are doing.”—Jesus

In a recent interview by the New York Times, a more contemporary thinker, Neil Barofsky, put it another way: "The incentives are to cheat, and cheating is profitable because there are no consequences." Are the financial markets a level playing field? Can anyone think otherwise? I don’t think so.

Do you?

Some will argue that the problems are trivial. For the markets to work, we have to believe that inside information is actually forbidden. We have to believe that the watchdogs of finance, the rating agencies, congress, and such, are reliable and fair. Yet, in my judgment, Christopher Lasch was right when he claimed that we are in an age of narcissism. And narcissism and integrity don’t go together.

Think about a bad drought, when a lake is full, everything looks great, but when it dries out you see all the crap sitting around at the bottom. This is what’s happening.

- Bernard Madoff’s financial fraud would not have been exposed if it weren’t for the financial crisis within the United States.

- Countrywide Financial Corporation would not have been prosecuted if the housing bubble continued.

- AIG would have continued on its merry selfish way, writing un-coverable insurance (at a big profit), if people didn’t need to collect post 2008.

- Would a little LIBOR skimming have even been noticed if it happened in good times? Now, the scrutiny is on. (Still, no one is going to go to jail.)

- Russell Wasendorf would not have attempted suicide if the markets had gone his way, and now he’s been caught $200 million short.

These crooks and alleged crooks often are wonderful in public. For instance, Bernie Madoff gave generously to charities, while Russell Wasendorf reportedly had “This messianic condition” in his town Cedar Falls in Iowa because of his contribution to the community. Everyone is admired for their public service, yet once caught; it becomes a different ball game.

Now, Let’s Talk About the Secret Life:

There is nothing psychological malignant about the secret life. We all need a place to be free to be ourselves. Society is very restricting, and sometimes an internal sense of freedom can be a Godsend. For instance, some have secret lives to be free themselves from a totalitarian state – or from a bad marriage. Others, for instance, have benign secret lives like cheating on diets or enjoying the pleasures of a beautiful man or woman from a distance. Where would the sweetness of life be without its secret, but benign, guilty pleasures?

But, secret lives can get out of hand; consider addictions.

A banker or financial professional can have a sex addiction, an internet addiction or even, bulimia, but it’s gambling and greed that should concern us. After all, unlike bulimia or alcoholism, they are hurting the public - and not just themselves or their family.

Greed in and of itself, is not inherently bad. When channeled, greed, like competition or vanity can be mobilized in socially acceptable ways. We need innovative ideas, new inventions, hospitals for the sick (even with someone’s name on it) and the dynamic energy of competition.

There is an ancient rabbinic story in which a great sage asked the Almighty to do away with the “evil inclination.” His wish was granted, but the world he saw was horrific. People were listless, roads not built, and while they lived peacefully, it was without a sense of vital human energy. “No, no, please bring back the evil inclination, I can’t stand it,” said the sage. Immediately, civilization reappeared, people were running around - and a real village returned.

Yet, greed left unchecked kills the golden goose of free market capitalism. The secret life exists whether you are trying to diet, if you have a gambling problem or you if live a double life of a sexual nature. You have personality A that conforms to social rules and mores. Then, in a psychological sleight of hand, you morph into personality B that conforms to other, more internally demanding standards.

The secret life is always about breaking free. In its adaptive sense, you secretly express yourself; your imagination, your sexuality, or your dreams. As mentioned, sometimes it’s the secret life of guilty pleasures that make life more interesting. Sometimes the secret life is about escaping oppression; but here we are concerned about the greedy having a secret life of rampant greed. The news shouts it out to us like a never ending ticker tape: our bankers and financial professionals are vulnerable to the manipulation of their own minds.

It is remarkable, how perfectly nice people can have the strangest ability to live two separate lives.

Are these crooks and alleged crooks simply sociopaths? Let’s consider it.

Indeed, there’s a class of individuals who are sociopaths and need not live a secret life; they are in little conflict over the wrongs they do. Right and wrong is meaningless to them; winning is everything. They keep things secret as a strategy of winning. Once caught, they have no guilt or shame. If you are living a secret life, the clash of you’re A personality with the deeds of your B personality will bring the feeling of failure, shame and guilt. You let people down. That is why some consider suicide.

The secret life is preserved for the vast majority of people who have some sense of right and wrong; of moral fiber. For those, putting lots of money in front of them encourages not just risk taking, but the possibility of graft.

It is the sneaky and sometimes childish way the mind works.

So, next time you open the paper I challenge you not to find something related to the secret lives of financial professionals. Unfortunately, these not so secret lives often dominate the headlines. What I wouldn’t give for a nice banker’s sex scandal, that hasn’t cost any of us a dime.

(For the record, this is a joke in bad taste. No one should wish ill on any family and the public need not know what people do in the privacy of their bedrooms.)

Money, greed, right and wrong, riches, regulations, and the secret life, makes for a major contemporary problem. We want the markets to work. We don’t want our financial players to be hamstrung into inactivity because of oversight, yet we also know that, for many, the mind has the power to self deceive, particularly, if the candy is sweet enough. And, these misdeeds can ruin our system.

What can be done?

In the coming conclusion of this series on greed and the mind, we'll offer a psychologically based solution that can help you, and with luck, help our institutions as well.

---------------------------------------------------

The Intelligent Divorce book series, online course and newsletter is a step by step program to handling divorce and intimate relationships with sanity.

You can hear Dr. Banschick on The Intelligent Divorce radio show as well.