Relationships

Thin Slices of Desperation

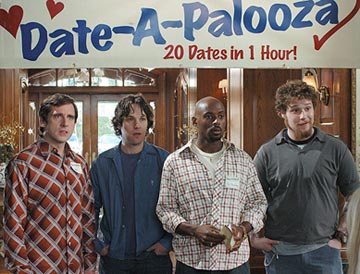

Don’t act hammy at speed dating events.

Posted October 18, 2009

For at least a few decades, social and personality psychologists have been testing how much people can infer from others' "thin slices of behavior". This tasty concept involves either giving participants a limited number of cues about a person (such as still photos of faces or outlines of bodies in motion) or limiting the time they have to process those cues. It turns out that people can extract a surprising amount of information from such sparse stimuli, including the target's physical attractiveness, personality, intelligence, masculinity and femininity, and even sexual orientation, to mention just a few. There was likely strong selection for this kind of ability, which in the ancestral environment would have been highly useful for quickly inferring strangers' intentions, strengths and weaknesses, mate value, and so on.

Lately, there has been a rash of especially exciting studies in this vein, some of which have used speed dating to examine quick judgments in the mating domain. For now, I am specifically going to focus on a 2007 study in Psychological Science by Paul Eastwick and colleagues. This must have been a fun study to run, because not only did the researchers get to play blind matchmaker, but they were also able to provide an answer to something we have all been wondering: when someone is desperate, is it obvious? The answer turned out to be yes. Their participants came in for a speed-dating event and talked to each of their dates for 4 minutes. After the event, they rated how they felt about each interaction partner in terms of romantic/sexual attraction, interpersonal chemistry, and desire to have another date with them (yes or no). Moreover, they estimated how selective each partner was, as measured by how many people that person would say "yes" to.

Results showed that one can easily detect desperation from all the way across the speed-dating table. First of all, there was a significant positive correlation between daters' perceived selectivity and actual selectivity. In other words, people who had low standards somehow leaked this information to the other daters. Second, after performing some deceptively complex statistical kung fu, the authors showed that Jack's attraction to Jill - above and beyond his baseline level of attraction to everyone in general - positively predicted Jill's attraction to Jack. In contrast, Jack's baseline attraction to everyone in general negatively predicted Jill's attraction to Jack. Or, as the authors themselves elegantly put it, "If a participant uniquely desired a particular partner, the partner tended to reciprocate that unique desire. If a participant generally tended to romantically desire others, those others tended not to desire him or her." Third, a mediation analysis showed that relatively indiscriminate daters' perceived lack of selectivity was in fact a big reason why they were not liked by other daters. So in summary, indiscriminate daters were perceived as indiscriminate and were also less liked, partly for this very reason.

Results showed that one can easily detect desperation from all the way across the speed-dating table. First of all, there was a significant positive correlation between daters' perceived selectivity and actual selectivity. In other words, people who had low standards somehow leaked this information to the other daters. Second, after performing some deceptively complex statistical kung fu, the authors showed that Jack's attraction to Jill - above and beyond his baseline level of attraction to everyone in general - positively predicted Jill's attraction to Jack. In contrast, Jack's baseline attraction to everyone in general negatively predicted Jill's attraction to Jack. Or, as the authors themselves elegantly put it, "If a participant uniquely desired a particular partner, the partner tended to reciprocate that unique desire. If a participant generally tended to romantically desire others, those others tended not to desire him or her." Third, a mediation analysis showed that relatively indiscriminate daters' perceived lack of selectivity was in fact a big reason why they were not liked by other daters. So in summary, indiscriminate daters were perceived as indiscriminate and were also less liked, partly for this very reason.

Two other things are important to note: the above results held for both men and women, and participants' physical attractiveness had nothing to do with it. One might imagine that less attractive daters were both less choosy and less desired by others, which would have been a pretty obvious and boring result. But there was more to it than that, as the results persisted even after statistically controlling for attractiveness.

Now, as far as slices go, a 4-minute live interaction is to a 5-second video clip as a hearty chunk of holiday ham is to Philly cheesesteak, but this doesn't make these results any less fascinating. In fact, as most good research does, this study provides more questions for future research than answers. The first question is how: how were the participants able to detect low (or high) dating standards in others? Was it the excessive perfume, the promiscuous twinkle in another person's eye, or the possibility that certain participants asked every one of their dates to have sex on the spot? Remarkably, people must have extracted information about each of their interaction partners' romantic interest in other people without observing almost any of their actual interactions with other people. The only way they could have watched other people talk to each other is if they had all awkwardly milled around together while waiting for the event to start, before a confused research assistant opened the door and started the fireworks.

Now, as far as slices go, a 4-minute live interaction is to a 5-second video clip as a hearty chunk of holiday ham is to Philly cheesesteak, but this doesn't make these results any less fascinating. In fact, as most good research does, this study provides more questions for future research than answers. The first question is how: how were the participants able to detect low (or high) dating standards in others? Was it the excessive perfume, the promiscuous twinkle in another person's eye, or the possibility that certain participants asked every one of their dates to have sex on the spot? Remarkably, people must have extracted information about each of their interaction partners' romantic interest in other people without observing almost any of their actual interactions with other people. The only way they could have watched other people talk to each other is if they had all awkwardly milled around together while waiting for the event to start, before a confused research assistant opened the door and started the fireworks.

The second, equally interesting question is why: why were the people who liked everyone less liked themselves? The answer is not as obvious as it might seem. After all, as the authors themselves pointed out, it is almost canonical in social psychology that liking breeds reciprocal liking. However, before this study, this truism had rarely, if ever, been examined in the context of romantic liking. In this arena, it makes sense that liking should only be appreciated if it is specific to oneself, because people desire partners who are committed to them.

Another potential reason they are not preferred is that low choosiness signals (to both others and to themselves) that one must not be a scarce or highly sought-after commodity. In another speed-dating study, the same group of researchers showed that the mere act of physically approaching potential dating partners (a proxy for who desires whom more) makes the approachers less choosy and the approachees more so. Finally, a New York Times piece that covered the current paper suggested that people might simply prefer others who are similar to them in terms of pickiness. While this is possible, it is not particularly plausible, for the same reason that less attractive people pair with each other not out of preference, but out of necessity. These individuals still prefer to be with others who are more attractive, but end up with similar others by virtue of the mating market settling on an assortative equilibrium. In the case of the study I've been talking about, most people likely desire the more choosy individuals because of their (heretofore unspecified) attractive qualities, but not everyone can get them; only other choosy individuals can.

So what have we learned? As usual, the lesson is that liking people is bad. You hear that, boys and girls? At speed dating events, don't go around smiling at everyone - just be nice to a few people and treat everyone else like crap. That will get you a bunch of follow-up dates in no time, where you will be able to assess a thicker slice of behavior.