Mindfulness

Is Mindfulness Being Mindlessly Overhyped? Experts Say "Yes"

Scholars want more rigorous science and less hype of so-called "mindfulness."

Posted October 10, 2017 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

A multidisciplinary team of 15 experts from renowned institutions and universities across the United States is calling for more rigorous science, less media hype, and clearer definitions of what is vaguely referred to as "mindfulness."

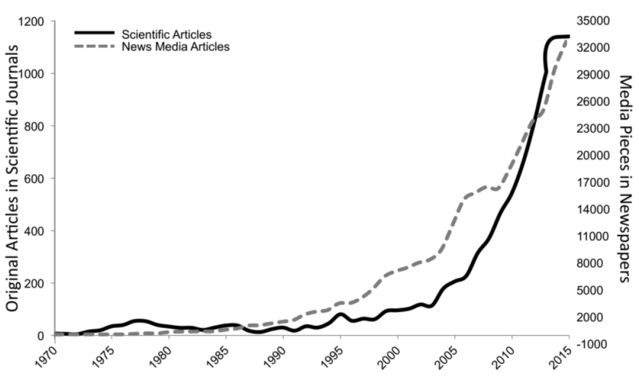

In the introduction of a paper, “Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation," recently published in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, the authors explain the impetus behind their somewhat urgent call-to-action regarding mindfulness: "Over the past two decades, writings on mindfulness and meditation practices have saturated the public news media and scientific literature (see graphic below). While this is not an isolated case, much popular media fail to accurately represent scientific examination of mindfulness, making rather exaggerated claims about the potential benefits of mindfulness practices. There have even been some portrayals of mindfulness as an essentially universal panacea for various types of human deficiencies and ailments. As mindfulness has increasingly pervaded every aspect of contemporary society, so have misunderstandings about what it is, whom it helps, and how it affects the mind and brain."

"Our goals are to inform interested scientists, the news media, and the public, to minimize harm, curb poor research practices, and staunch the flow of misinformation about the benefits, costs, and future prospects of mindfulness meditation," the authors state in the abstract of the aforementioned paper.

In a statement, co-author Willoughby Britton, an assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University and co-director of The Britton Lab, said: "We are sometimes overselling the benefits of mindfulness to pretty much any person who has any condition, without much caution, nuance or condition-specific modifications, instructor training criteria, and basic science around mechanism of action. The possibility of unsafe or adverse effects has been largely ignored. This situation is not unique to mindfulness, but because of mindfulness's widespread use in mental health, schools, and apps, it is not ideal from a public health perspective."

One of the biggest problems facing "mindfulness" is that the term itself is murky and inconsistently defined in both scientific literature and popular media. According to the authors: "There is neither one universally accepted technical definition of 'mindfulness' nor any broad agreement about detailed aspects of the underlying concept to which it refers." The lack of a clear-cut definition undermines the ability to effectively research and prescribe mindfulness-based interventions.

To illuminate how vague the terminology surrounding mindfulness has become, the authors write: "Frequently, 'mindfulness' simply denotes a mental faculty for being consciously aware and taking account of currently prevailing situations. At other times, 'mindfulness' may refer to formal practice of sitting on a cushion in a specific posture and attending (more or less successfully) to the breath or some other focal object. Considerable disagreement about definitions is not uncommon in the study of complex constructs and mindfulness is no exception. Mindfulness is typically considered to be a mental faculty relating to attention, awareness, retention/memory, and/or discernment; however, these multiple faculties are rarely represented in research practice."

"Any study that uses the term 'mindfulness' must be scrutinized carefully, ascertaining exactly what type of 'mindfulness' was involved, what sorts of explicit instruction were actually given to participants for directing practice," the authors emphasize. "When formal meditation was used in a study, one ought to consider whether a specifically defined type of mindfulness or other meditation was the target practice."

The authors warn: "Without specific, well-defined terms to describe not only practices but also their effects, studies of interventions such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) cannot provide valid and comparable measurements to produce reliable evidence." In an attempt to provide some type of remedy to this situation, Van Dam et al. offer a "Nonexhaustive List of Defining Features for Characterizing Contemplative and Meditation Practices."

The burgeoning field of mindfulness research is lacking consistency and often fails to meet rigorous scientific protocols.Therefore, the authors said: "We recommend that future research on mindfulness aim to produce a body of work for describing and explaining what biological, emotional, cognitive, behavioral and social, as well as other such mental and physical functions, change with mindfulness training." To facilitate this process, their paper includes a "Nonexhaustive List of Study Design Features for a Mindfulness-Based Intervention."

Ultimately, the authors' primary concern is that insufficient research and media hype can mislead the general public into believing that "mindfulness" training is some type of broad-based panacea or cure-all. The truth is that mindfulness interventions may only help certain demographics or people in specific circumstances. The authors drive home the point that "much more and much better, scientific studies are needed to clarify these matters. Otherwise, people may waste time and money, or worse, suffer needless adverse effects."

In the conclusion, the 15 co-authors lay out some actionable next steps and hurdles relating to their mindfulness clarion call: "Contemplative psychological scientists and neuroscientists, along with other researchers who study mental processes and brain mechanisms underlying the practice of mindfulness and related types of meditation have a considerable amount of work to make meaningful progress. Much work should go toward improving the rigor of methods used, along with the accuracy of news media publicity and eliminating public misunderstandings caused by past undue 'mindfulness hype.' These efforts have to take place on several related fronts...Only with such diligent multipronged future endeavors may we hope to surmount the prior misunderstandings and past harms caused by pervasive mindfulness hype that has accompanied the contemplative science movement."

As a side note: In the acknowledgments of this paper, the authors said, "We dedicate this article to our dear friend and colleague, Cathy Kerr, who passed away unexpectedly during the revision of this work. Cathy was among the key driving forces that led to this particular group forming and to our formal meeting in Amherst, Massachusetts, in July 2014. Cathy touched so many lives and had a profound influence on the variety of ways that many of us approach mindfulness and meditation research. She will be profoundly missed."

References

"Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation" by Nicholas T. Van Dam et al. Perspectives on Psychological Science. (Article first published online: October 10, 2017) DOI: 10.1177/174569161770958

Author & Affiliation Information:

Nicholas T. Van Dam: Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Marieke K. van Vugt: Institute of Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Engineering, University of Groningen

David R. Vago: Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, Departments of Psychiatry and Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Laura Schmalzl: College of Science and Integrative Health, Southern California University of Health Sciences

Clifford D. Saron: Center for Mind and Brain, University of California, Davis

Andrew Olendzki: Integrated Dharma Institute

Ted Meissner: Center for Mindfulness, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Sara W. Lazar: Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Catherine E. Kerr: Department of Family Medicine, Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University (*Cathy Kerr passed away unexpectedly during the revision phase of this paper.)

Jolie Gorchov: Silver School of Social Work, New York University

Kieran C. R. Fox: Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University

Brent A. Field: Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Princeton University

Willoughby B. Britton: Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University

Julie A. Brefczynski-Lewis: Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, School of Medicine, West Virginia University

David E. Meyer: Department of Psychology, University of Michigan